Ivan Putrov

Men in Motion

London, Sadler’s Wells

27 January 2012

After all the fuss about Sergei Polunin abruptly leaving the Royal Ballet, guess who stole the Men in Motion show? Daniel Proietto, in the AfterLight solo Russell Maliphant made for him in 2010. Admittedly, you could read the 15-minute solo as a warning of the fate awaiting a troubled dancer deprived of the support of a company of colleagues – if you know your Nijinsky. But for those unaware of the inspiration for the piece (created for a Diaghilev tribute), Proietto’s performance was none the less magnificent.

Ivan Putrov produced the show to display the talents of his fellow male dancers, along the lines of the Kings of the Dance programmes that have toured the United States and Russia. He was frustrated by the non-appearance of two Russians (Semen Chudin and Andrei Merkuriev) due to visa problems, so had to cancel the scheduled Remanso trio by Nacho Duato, which he would have performed with them. No great loss, unless you’re a Duato fan, but it would have made a more rousing finale than Putrov’s own creation, Ithaka.

The evening worked perfectly well, however – by all accounts far better than the overloaded Kings of the Dance showcases to recorded music. We were blessed with the Music Projects orchestra, conducted by Richard Bernas, with Philip Gammon as guest pianist. The programme opened with a version of Le Spectre de la rose licensed by the Fokine Estate, though bearing little resemblance to other accounts, including the one danced by Putrov with the Royal Ballet. I don’t recall the sleeping girl waking up halfway through to smile happily into the spectre’s eyes before returning to her chair. Elena Glurdjidze (English National Ballet) was charming as the debutante, watched over by Igor Kolb (from the Mariinsky) in dusky pink allover tights and a sprinkling of petals. In spite of the unbecoming hat he was far from andogynous: impressively controlled multiple pirouettes, though with conspicuous preparations, and a fine jump. He didn’t spend much time posing on demi-pointe, which Nureyev apparently used to find the most tiring part of the choreography – if indeed it was Fokine’s choreography.

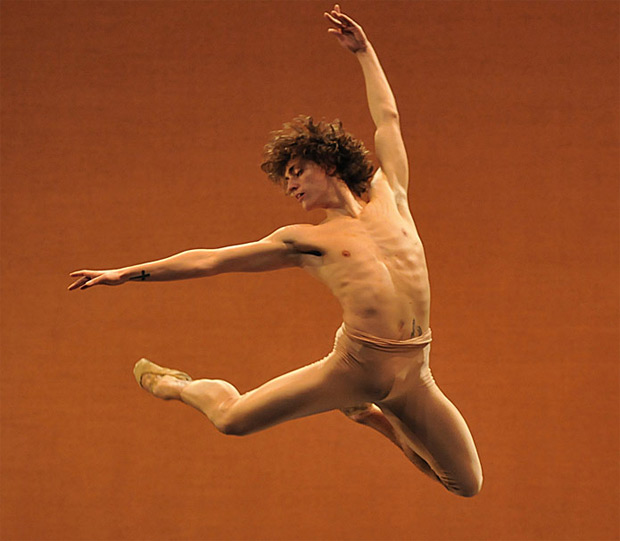

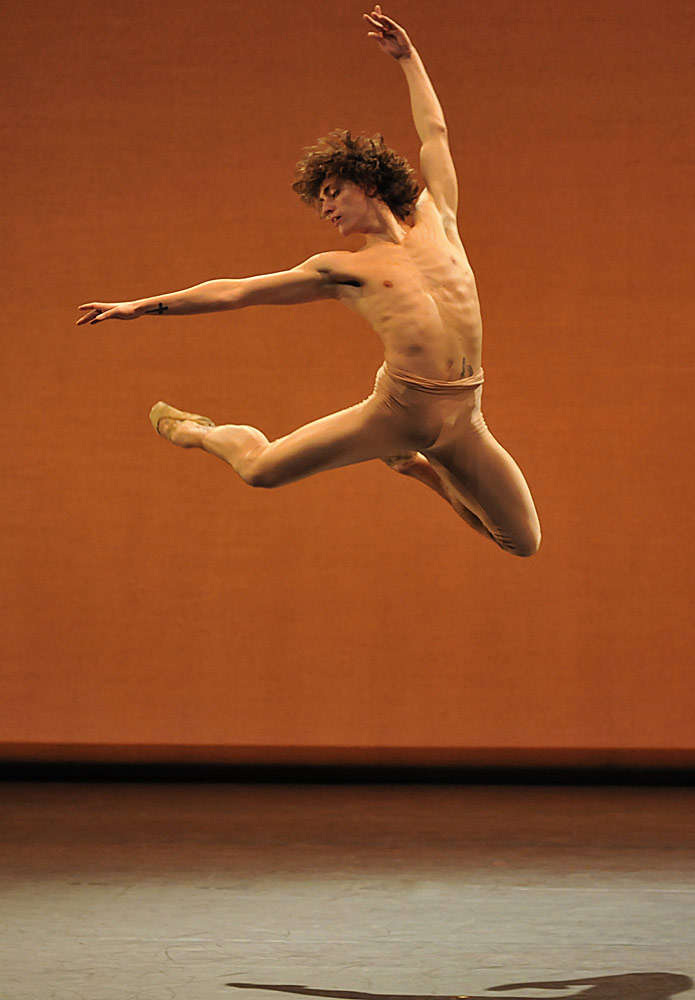

Polunin came next in the Narcisse solo by Kasian Goleizovsky, sometimes danced at Russian galas. Vladimir Vasiliev used to do it, as did Vladimir Malakhov; Nikolai Tsiskaridze performed it in London at a Coliseum gala, self-regarding in bright blue tights with eye shadow to match. Polunin was bathed in a golden glow, his bare torso decorated with glitter: no tattoos visible beneath the body makeup. Goleizovsky’s Narcissus is a farouche faun, bounding like a goat in spectacular leaps, pausing to play imaginary pan pipes. The choreography resembles one of those artistic gymnastic routines in which virtuoso elements are interspersed with twiddly bits to give the performer time to breathe before the next feat.

Polunin carved his way around the stage, more feral than fey, every shape immaculate. He is a truly remarkable dancer: I refuse to believe we shan’t be seeing more of him in the near future. Yet the solo’s ending seemed almost prophetic, as doomed Narcissus shielded his eyes from a spotlight representing his reflection in a pool of water before drowning, dazzled.

Putrov had the hard task of following on in a deceptively simple solo by Ashton, to music for the Dance of the Blessed Spirits in Gluck’s opera Orpheus and Eurydice. Ashton had re-choreographed it for Antony Dowell in 1978, for an ENO gala at the Coliseum, and it had not been seen in Britain for over 30 years. Dowell taught it to David Hallberg for a Kings of the Dance tour and has now passed it on to Putrov. Ashton’s contrasting dynamics, with shifts of direction at the end of phrases, are so much subtler than those in the Goleizovsky piece that they risk going unnoticed, along with the suggestion that the questing figure might be Orpheus. Putrov sustained the solo beautifully, his landings soundless.

After the interval came AfterLight (Part One), to Satie’s Gnossiennes. Maliphant based it on Nijinsky’s writings as he descended into madness, and on his obsessively circular drawings. Proietto describes great arcs of movement in a space restricted by light, dappled with dark, torn edges. (Lighting by the wonderful Michael Hulls). Through his fluent body, striving and falling, Proietto reveals the soul of a dancer, lost in his mute world. There are echoes of the Spectre de la rose, of the Faune, of Petrushka, as well as of Nijinsky’s spiritual ravings. This was not a display of hard-earned technique but a visceral communication of feeling – which the audience understood. Proeitto received the loudest and longest applause of the evening.

Daniel Proietto in an excerpt from AfterLight Part 1 by Russell Maliphant. © Russell Maliphant Company.

Putrov commissioned Gary Hume to design the set for Ithaka, based on the 1911 poem by Cavafy describing a mythical journey. The phases of the journey are suggested by differently coloured panels along the sides, with a dark window at the back of the stage. The delightful music is from Paul Dukas’s 1912 ballet La Péri. Putrov is the possibly naïve protagonist in yellow tights, who starts out in a series of manèges of repeated steps before sinking to the ground. Enter Aaron Sillis in turquoise tights, his dark hair long and flowing. He seems a sinister, seductive spirit, apt to mislead or mistreat the Putrov figure. Enter Elena Glurdjidze, flirtatiously stepping on pointe like the Doll in Petrushka. Actually, the three characters are most like those in Tetley’s Pierrot Lunaire (which Putrov has performed): innocent Pierrot, taught the harsh lessons of life by Brighella and Columbine. The ambiguous ending is similar, with all three unable to escape each other. Putrov’s choreography is unremarkable, ignoring the insistent rhythms in the music but serving his purpose of outlining a learning curve of relationships. His biog. in the programme proclaims him Dancer, Producer and Choreographer: he still has a way to go before being able to deserve the third description.

This production of Spectre de la Rose was not staged by anyone at the Fokine Estate. “Performed with the permission of” is a copyright credit, not a staging credit. Mr Putrov learned Spectre at the Royal Ballet.