Paris Opera Ballet

La Bayadère

Paris, Opera Bastille

7 March 2012

www.operadeparis.fr

So much of our reaction to this or that production is determined by what we’ve seen before; it’s nearly impossible to be objective. For example I’ve always adored Balanchine’s Nutcracker, and until recently would have argued vehemently that it was absolutely right to have Marie and the Nutcracker Prince walk off into the snowy forest during Tchaikovsky’s sumptuous forest of firs in winter music, rather than introduce a pas de deux at this point. Why muddle matters with another classical pas de deux here? Well, after watching several performances of Alexei Ratmansky’s Nutcracker for ABT, I’ve begun to change my mind. A pas de deux works just fine, thank you very much.

La Bayadère is a different matter. First of all, most of us discover it as adults. And, unless we’re Russian, it’s unlikely to be a ballet terribly close to our hearts: it’s a little too camp, with its archaic Indian setting, all fakirs and parrots. Many of the dances—and much of the music—are best described as dance-hall exotique. The score is certainly not one of Ludwig Minkus’s finest moments. But, I’ll admit that, in the right hands, the plight of Nikiya, a temple dancer indentured to a high priest but secretly in love with a warrior who, in turn, is betrothed to a princess, can be quite poignant. Who doesn’t understand a love triangle, mixed with issues of rank and class? And, like many before me, I have been mightily stirred by the sheer splendor of the corps de ballet in the famous Kingdom of the Shades scene, in which the dancers descend an incline, one after another, to enact a celestial ritual, ebbing across the stage in waves or slowly raising a leg or turning in place, moving as one body, one soul. (The trance is usually broken by wobbles, but no matter). As Tamara Karsavina said in 1965, the Shades (spirits) should appear as “une chaine d’ombres, une brume s’élevant en nuages”* (a line of shadows, a mist rising in clouds), or, in a more Eastern interpretation, like the repetitive figures in a Mandala.

The Bayadère we are used to seeing in New York (and London) is Natalia Makarova’s, created in 1980 for American Ballet Theatre. She was the first to set a complete version of the ballet on a Western company; until then, only Russian companies performed it in full. In fact, the ballet was almost unknown in the West until the Kirov brought it to Paris in 1961, with Nureyev in the role of Solor. One thinks of Makarova’s version as canonical, but in fact she had made many changes to the ballet she had learned as a young woman at the Kirov. She restored the final act, in which a massive earthquake—heaven-sent, of course—kills the warrior and the princess during their loveless wedding. This scene had been eliminated in Russia after the Revolution, because it was too complicated and expensive to stage. Most of the choreography in this final act is by Makarova, and the music is a kind of Minkus pastiche by John Lanchbery. (The original score was unavailable in the west and the choreography had been more or less forgotten after so many years out of the repertory.) It’s imperfect, but it gives the story some closure. Makarova moved things around; she cut as well, mostly folksy character dances that added color to the engagement party in the second act. Somehow, though, it all works. The story has an arc; the haughty princess has a chance to reveal that she, too, longs for love; the apotheosis of the two lovers, connected by a white ribbon, makes sense. The cuts do dampen some of the color, but they also keep the whole evening to a manageable length.

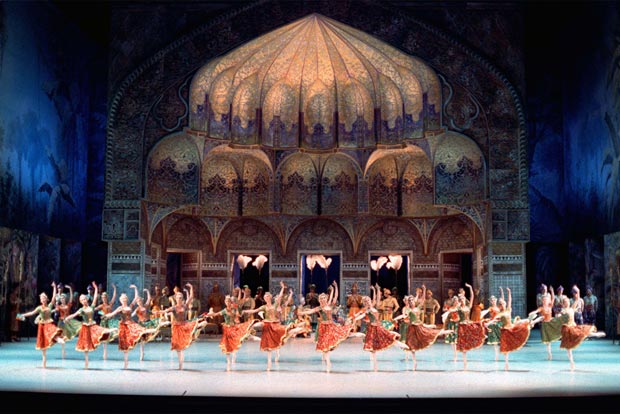

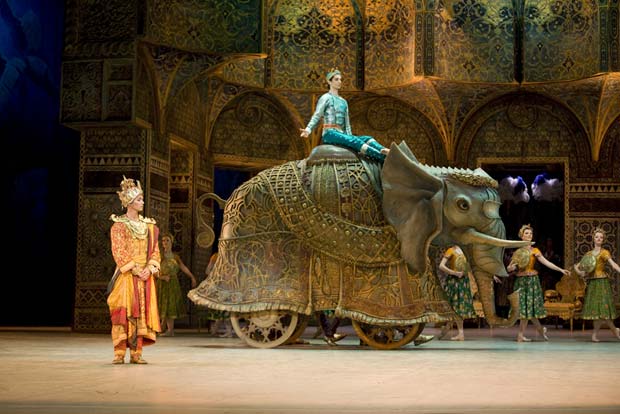

It is with this in mind that on March 7 I saw the Paris Opéra Ballet’s performance of La Bayadère, created for the company in 1992 by Rudolf Nureyev. He was already very, very ill (the ballet opened in October, and he died in January of the following year). It was Nureyev’s last project as director of the Opéra, and because of his physical state, there were things that he was unable to do—he too had wanted to restore the final act, for example. He had had Minkus’s original music transcribed for him in Russia. There are reports that the sumptuous sets, by Ezio Frigerio, were not completely to his liking. But as with Makarova’s staging for ABT, the first re-creation of La Bayadère was a milestone for the company.

The cast on March 7 was tops. Two étoiles, Aurélie Dupont and Dorothée Gilbert, performed the roles of Nikiya (temple dancer) and Gamzatti (princess). A premier danseur (though, as we shall see, not for long) danced the role of Solor (warrior). And in the pit: the guest conductor Fayçal Karoui, also music director at New York City Ballet (until the end of the spring season). From the first bars of the overture, one thing was clear: this would not be an elegiac, dreamy reading of the score. Quite to the contrary: Karoui, as is often his wont at New York City Ballet, kept things going at a brisk pace, emphasizing the bombastic, dance-hall aspects of Minkus’s music, as if it were more pastiche than the real thing. Karoui is a strong, intelligent conductor, with style and charm and a sense of humor, but he tends to hold back from the deepest, most expansive moments of emotion, as if they embarrassed him. This approach works well, with, say, Donizetti’s opera music in Balanchine’s Donizettti Variations, or in Delibes’s Sylvia, but I have often lamented Karoui’s un-Romantic reading of Tchaikovsky (especially in Serenade and Sleeping Beauty). As it turned out, on this night his conducting magnified the razzle-dazzle of numbers like the dance of the fakirs in Act I and the danse indienne in Act II, but undercut the dreamy lyricism of the Shades scene and the pathos of Nikiya’s slow, pleading dance at the end of the second act. The sound was clean and crisp, but lacked poetry.

It wasn’t just Karoui’s conducting, though. From the beginning, the production gave off a certain air of aloofness, a concern with good taste, except in the more colorful character dances, when the dancers seemed to feel it was all right to let go and have some fun. The fakirs danced their chest-slapping knife number with gusto, and the wild, thumping danse indienne in the second act was an over-the-top, vaudevillian fantasy, and a total hoot. I will miss it next time I see the Makarova version. Another charming number was the so-called Manu solo, in which a dancer pretends to balance a jug of water on her head while teetering and skipping on pointe, all the while fending off two little girls (also on pointe) who pull at her skirts. (The insistent little pests were performed by two petits rats of the Paris Opera school). Mathilde Froustey was adorable as the jug-carrier, light and playful, fluttering her eyes coyly to maximize her charm. (On the other hand the Golden Idol variation, danced by Emmanuel Thibault, usually such a stand-out, was rather ho-hum. And I’m not sure how I feel about his côterie of young boys in blackface, which Makarova also eliminated.) But one the whole, with the notable exception of Dorothée Gilbert, a volatile Gamzatti, the acting was very reserved, I would say even dry. Both the High Brahmin and the Rajah were too young for their roles, and given the company’s brand of hyper-stylized, un-emphatic mime, the result was an insufficient build-up to the main conflict. Nikiya must feel threatened by the Brahmin; after all, as a high priest he is her master, and he can destroy her, and threatens to. Here, he seemed to just go through the motions.

But more importantly, the dancers in the roles of Solor and Nikiya must make us believe in their longing for each other, and in the desperation brought on by their circumstances. In Nikiya’s plea during the betrothal scene – a slow, aching adagio – Nikiya expresses her emotion with the deep arch of her back, the sinuousness of her lines, and with the momentary pre-shadowing of the phrase that will be performed by the Shades: step forward into arabesque allongée, reach, step away, arch backward. The entire solo is a lament. But in this moment, and throughout the ballet, Aurélie Dupont was simply too erect, too proud, too regal, too cold. She is an extraordinarily beautiful woman, and a dancer of great clarity and purity of line, but in this role, or at least in this performance, she did not create phrases with movements, or a lush, fluid melody with her body. She wove no no exotic aura around her. Her plaintive solo, especially, came across as a series of disconnected gestures. (Nureyev also chose to keep the almost gypsy-like allegro that follows the adagio, which Makarova cut. It rather breaks the mood.)

The role of Solor was well danced, but under-interpreted by the young Josua Hoffalt. His jumps are light and expansive—though his final variation had some rather stiff landings—and his footwork is exemplary in its crispness and clarity. He has a lovely line in attitude. He is polished and musical and precise, and his partnering is capable if not inspired—he seemed to have a little bit of trouble keeping Dorothée Gilbert on balance in her turns in their second-act pas de deux. But he showed little personality. There was no sense of the pride and panther-like grace of the warrior, the passionate desire of the lover, the despair of the man whose fate is out of his control. He was essentially the same throughout the ballet, as if events were simply happening around him, without his direct participation. He was perhaps overwhelmed by the fact that there were rumors he would be promoted to the highest rank—étoile—that night, as, in fact, he was. And he is young (twenty-seven), so he may well develop a fuller interpretation of the role with time. But it may also be a matter of taste. In an article the following day, the critic in Le Monde (Rosita Boisseau) wrote of his performance: “Hoffalt perfectly took on the role of the warrior Solor, not an easy task. Too expressive, he becomes ridiculous; too self-effacing, he lacks substance.” Hoffalt’s performance erred on the side of good taste, of avoiding the ridiculous.

A deficit of expressivity also undermined the power of the Shades scene—the heart of the ballet. Echoing Karoui’s crisp interpretation of the music, the trance-like sequence was performed cleanly, precisely, but almost mechanically. The spell never quite took hold. As Karsavina wrote in the sixties of a performance at Covent Garden, “Il ne me semblait pas que ces danseuses représentaient des ombres immatérielles, mais bien plutôt qu’elles passaient un examen difficile” (it did not seem to me that these dancers represented immaterial shadows but rather that they were undergoing a difficult test). * The level of dancing in the company, however, is very, very high. Seldom does one see such crystalline execution throughout the ranks, in all roles, big and small. The children were equally impressive. The costumes were detailed and luxurious, and how many of them there were! Nikiya changed at least four times. This is, doubtless, a great company.

Dorothée Gilbert, as Gamzatti, was excellent, both in her dancing and in her acting. In her scene with Nikiya, Gilbert’s fiery temperament, intermixed with confusion and hurt pride, brought to story to life. In this version Gilbert and Dupont come to blows, scratch at each other, even roll around on the floor. For a moment, the two were no longer a princess and a dancing girl, but two beautiful women fighting over a man. Gilbert looked like she might tear one of Dupont’s eyes out. A tricky series of attitude turns and fouettées in her third-act variation was also dispatched with aplomb. There were other standouts. One of the shades, Héloïse Bourdon, captured the eye, with her lovely jump and easy turns (and beautiful, fluid arms). It turns out that she is a sujet in the company (roughly a soloist, in US terms) and that she will be débuting in the role of Nikiya on March 24, alongside the handsme Stéphane Bullion. I would be curious to see it.

In the end, Nureyev chose to close the ballet with the Shades act. When the curtain came down, my guest, whose first Bayadère this was, asked: Is that it? Without a final act or some sort of postlude explaining the fates of the characters, it is not a very satisfying ending. No matter, the audience in the packed auditorium of Opéra Bastille rose to its feet enthusiastically. But this was only the beginning; the curtain came up once again, and Brigitte Lefèvre (artistic director of the ballet) and Nicolas Joel (director of the opera as a whole) emerged to announce the promotion of the evening’s Solor, Josua Hoffalt, to the ultimate rank: étoile. There were buckets of tears, from Hoffalt, Gilbert, and Dupont. In fact, it was the high point of the evening. An uncontrolled release of emotion, at last.

* From a 1965 talk, reprinted in the POB program.

Welcome aboard, Marina. Lovely review. I was wondering about Faycal; sounds like he conducted much as I’d expected. It does seem like the POB style is dry to the point of aridity. Every time I try to watch the video of their Emeralds I have to give up as I feel the oxygen getting sucked out of the room.

Thanks, Eric. A tad dry, but those character dances were fun…

The thing that baffles me is If the music, coiumtsng, and dancing all do not evoke India, then the only thing Indian about the ballet is that the synopsis in the program claims that it is set in India? It seems like the simple solution is just to ditch the setting and move it somewhere else. It doesn’t really matter, since the coiumtsng, music, and dancing could just as easily not belong somewhere else! Yes, it sounds funny, but it is extremely common in the opera world to goof with settings, put things even in odd and non-sensical places. I saw a production of The Magic Flute in Zurich where the whole thing, instead of being in an enchanted forest, took place in a masonic library. It was odd, yet memorable.Though I do want to jump in with one little pedantic thing: It is very common for people to talk about Middle Eastern and Indian dance together, but they are two completely different things. Not only are then not related from a cultural or historical perspective, but movement-wise, they just don’t overlap very much. Indian dance includes little in the way of torso articulation, while middle eastern dance does not have any tradition of poses with assigned meanings. Though you are right that both include very expressive hand and wrist movements. There is a story that turns up in newspaper articles and the like periodically that talks about belly dance being traced back to Indian temple dances it is an amusing fiction, but absolutely not the case. It unfortunately comes up a lot when teachers want to assign mother-goddess-y origins to belly dance, even though it is the performance form of social dances done by women *and* men all over the middle east.

[…] Harss went in-depth Thursday on the Paris Opéra Ballet, which performs for the first time in Chicago this […]

[…] In early March, I went to Paris to see the Paris Opéra Ballet perform La Bayadère at the Opéra Bastille. You can read my review for DanceTabs here. […]