Scottish Ballet

A Streetcar Named Desire

London, Sadler’s Wells

26 April 2012

www.scottishballet.co.uk

Tennesse Williams’s Streetcar is a play involving sex, death, destitution and madness – ripe subjects for ballet: just think of Kenneth MacMillan’s and Boris Eifman’s bodies of work. Basing a narrative ballet on an existing text (or film) poses a familiar dilemma: does the audience need to know the source in advance, mug up the scenario in the programme – or should the danced version be self-sufficient?

For Scottish Ballet’s Streetcar, Ashley Page, the company’s outgoing artistic director, brought together theatre director Nancy Meckler with choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa. Meckler, well-known for her work with her company, Shared Experience, had directed A Streetcar Named Desire for theatre some 15 years ago; Ochoa had never choreographed as story ballet before. Half-Belgian, half-Colombian, Ochoa launched her choreographic career in 2003 and has worked in ballet, contemporary dance, musical theatre, opera and fashion. She collaborated closely with Meckler and the composer, Peter Salem, who has often worked with Shared Experience, as well as in films, TV and dance-theatre.

The teamwork has resulted in a marvellously lucid re-telling of Williams’s themes and preoccupations. (I wouldn’t know how the ballet comes across to the innocent eye.) Meckler’s approach is the oppposite of Boris Eifman’s, in that she is concerned with the characters’ back stories and social context rather than purely their emotional turmoil. Where the play’s action is set in the present tense, gradually exposing Blanche’s lies about her past, the ballet recounts her youthful experiences in the Deep South before she arrives to meet her fate in New Orleans.

The opening image is of girlish Blanche DuBois in a full white skirt fluttering under a bare light bulb, an evocation of the play’s tentative title, The Moth. She will be burnt by the harsh light of reality, however much she craves the soft glow of illusion. As the music swells and a cast of atractive youngsters criss-crosses the stage, we see the setting: a projection of a Southern mansion, Belle Reve, in the 1930s. What we don’t know, unless forewarned, is that the well-off DuBois family celebrating Blanche’s marriage is about to be financially ruined. A sweet-sour waltz that will recur as a motif accompanies the wedding party. Blanche’s sweet young husband, Alan, leaves her arms for those of a seductive male guest. The music stops as she confronts and rejects her husband. He runs off stage and the sound of a gunshot cracks the silence. Alan dies bloodily in Blanche’s arms.

A parade of reproachful grey ghosts processes on breeze blocks behind guilt-stricken Blanche. This is the first of numerous uses of the corps as chorus, amplifying or commenting on the protagonist’s reactions – a device Meckler has used in Shared Experience productions. Then comes a cartoonish sequence of posed family photographs, the loud pop of a flash-bulb sound like a gunshot as one member after another falls dead. It’s kind of silly before the very effective theatrical shock of the mansion collapsing into a heap of rubble.

We’re still in the back story as the scene moves briefly to New Orleans, where Stella, Blanche’s younger sister, falls for working class Stanley Kowalski. Meanwhile Blanche, homeless, is living in a hotel, its neon letters spelt out by versatile breeze blocks. She encounters a succession of men for acrobatic sex, concluding with an under-age boy who reminds her of her husband: cue bloodied ghost. I didn’t feel that the choreography, or Eve Mutso’s performance at this point, conveyed Blanche’s empty neediness rather than lust.

Here lies the ballet’s essential problem: the desolate poetry of Williams’s writing has been replaced by over-literal action that advances the story but doesn’t provide balletic poetry in its own right. There’s nothing wrong with Ochoa’s choreography – ingenious if generic ballet-based contemporary dance. It just doesn’t get a chance to soar, either in pas de deux or solos (of which the few are very brief) which could reveal more of the characters’ inner lives. A major difficulty is that Blanche is a fantasist, trying to shape reality to fit her dreams, lying to herself as well as others: how to show, without the advantage of words, that she’s deluded, until she finally goes bonkers?

She’s driven out of town by a chorus of disapproving, stomping grey people: not entirely a fantasy, though presumably we see them through her eyes. The corps form themselves into a train, then into commuters, as she travels to join Stella in New Orleans. By now, half way through Act I, we’ve reached the point where the play starts in the 1950s, with Blanche’s intrusion into the apartment and marriage of Stella and Stanley. The ballet comes to vivid life with scenes in the cramped living space (more breezeblocks), at a bowling alley and in a nightclub: lots of opportunities for jazzy jiving, virtuoso leaping and louche behaviour. Blanche keeps her pointe shoes on, though Stella has abandoned hers, along with her genteel upbringing.

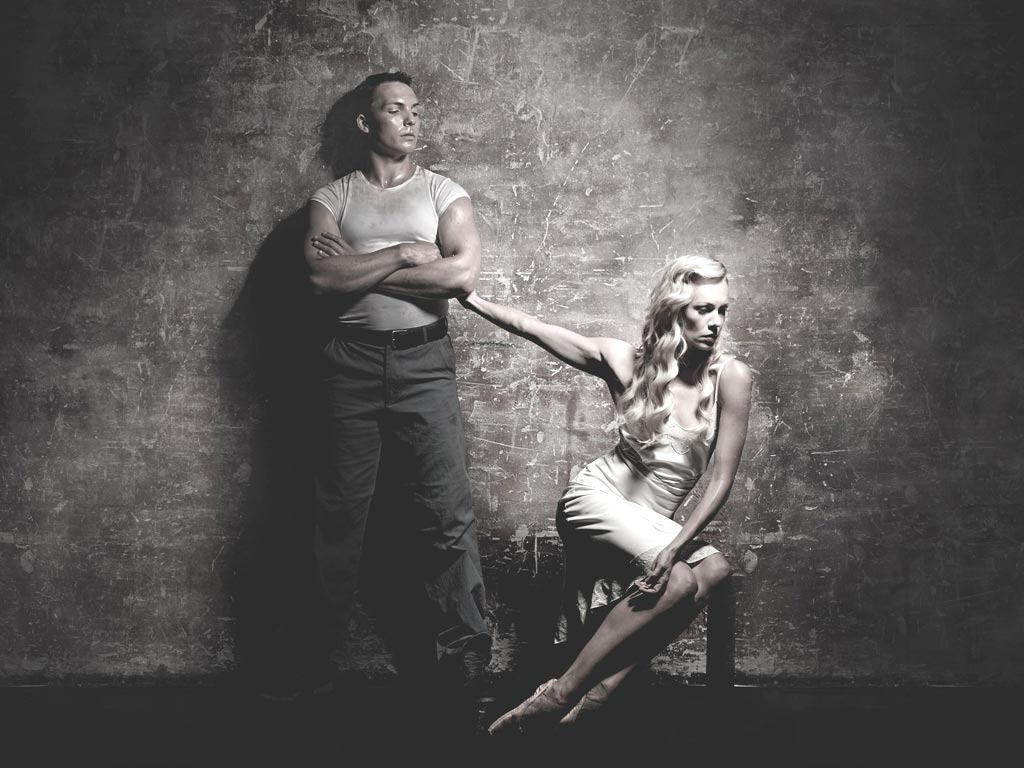

The sexual attraction between the married couple is fully established when Stanley gets drunk after a poker game, expresses his exasperation with Blanche’s interference in a conflicted solo and yells for Stella. In the scenario, he’s meant to be attacking her, but the pas de deux reveals his craving for her as she swoops around him like a fish on a line, ending up cradling him in her arms on the floor. She’s supposed to be pregnant, but ballet partnering can’t accommodate an early bump. When Stella jumps into his arms at the start of Act II, her leap is echoed by the corps women flinging themselves at bare-chested men. Everyone but Blanche, it seems, is enjoying passionate sex.

She has hit the bottle and keeps seeing visions of her blood-stained husband. She has pinned her hopes of married respectability on a beau, Mitch (Adam Blyde), a two-dimensional character with a comic hat and bouquet. His energetic dancing tells us little about him. Stanley ruins her chances with a letter – always tantalising in a ballet – revealing her promiscuous past. Cue reprises, under a lurid purple light, of her hotel couplings and a chorus of grey-clad disapprovers, some of whom become moth-women, amplifying Blanche’s distress. Figures from her early life reappear as drunken hallucinations. Far too literally, a dancer dressed as young Blanche recaps the doomed wedding scene, hands old Blanche a hip flask and helps her put on a pink-red ballgown. Blanche has gone from pure white to tainted red.

We’re in high melodrama territory, complete with reprises of the wedding waltz and a recording of Blanche’s favourite song, It’s Only a Paper Moon. A Mexican flower seller, brandishing paper flowers for the dead, puts in a second appearance, magnified this time as a sinister trio. Stanley, celebrating the birth of his child, dons a glittering dressing gown, smokes a cigar and brandishes a champagne bottle – or perhaps these are Blanche’s fantasies. He rapes her brutally, a reality she cannot face and that Stella has to refuse to believe. So Blanche is taken away by a man in a white coat, surrounded by a stageful of women in black with scarlet flowers for the dead in their mouths.

The imagery of flowers, moths, light bulbs, the colours of clothing and even the musical reprises are Tennessee Wiliams’s. Though they are ideal for a dance-theatre treatment, Meckler has kept rather too closely to the details of the play. (For example, the role of a character named in the cast sheet, Texan cowboy Shep Huntleigh, is inexplicable and unnecessary.) The many scene changes are effectively done by the cast moving the blocks of the set, but they leave little time and space for choreography to tell its own story in dance language. The main characters aren’t trusted to express their emotions in sustained solos without the corps de ballet intervening as a movement chorus. And Blanche doesn’t need to be reminded of her suicidal husband quite so often.

That said, the narrative is graphic and gripping. Scottish Ballet’s dancers prove themselves dramatic actors in supporting roles as well as principal ones. Tama Barry has a macho swagger and dumb vulnerability as Stanley; Sophie Martin switches convincingly from Southern belle to sensual, masochistic wife; and Eve Mutso retains an unexpected dignity as deluded, though far from craven, Blanche. Peter Salem’s music fits the action as aptly as a film score, combining atmospheric recorded sounds with live instruments. Because the musicians are amplified, unless you see them in the pit there’s no way of telling the entire score isn’t recorded – though the dancers will know.

This is a fascinating review: so well considered. I enjoyed the ballet very much; I found the staging,score, dancing and choreography excellent but it did not move me emotionally like those great nights at the ballet do. I have been struggling to understand why because the story itself has all the right ingredients – I wondered if the cast I saw on Friday evening had somehow failed to plumb the emotional depths but this review articulates exactly what isn’t quite right …. “The main characters aren’t trusted to express their emotions in sustained solos without the corps de ballet intervening as a movement chorus.” There are other examples too.

Very glad to read the comment in the last sentence about the score being recorded – I thought it was & I felt very stupid when the conductor appeared on stage for the curtain call.

I found the whole experience intensely satisfying. Dance, as a silent art, confronts a particular difficulty in conveying intricate narrative – Liam Scarlett’s “Sweet Violets,” enjoyable though it was, did not quite succeed in this. But in this case, a combination of director, choreographer, first-class score, and clever staging combined to make a complex story crystal clear. As a consequence, I felt that the choreography did not have to carry the full load of storytelling which, taking the whole as a theatrical event, did not concern me one bit. I hope that I’ll have the opportunity of seeing it again, somewhere.