The Aussie Invasion

Australian Ballet

Infinity Mixed Bill: Luminous (divertissements), Dyad 1929, Warumuk | Swan Lake

New York, David H. Koch Theater

June 2012

www.australianballet.com.au

Touring is a complicated business for a ballet company. There are mountains of logistics, fundraising, rehearsing, and fretting to do. And, seemingly the most difficult of all, choosing the right repertory. How can a company make a good impression with just a few performances of one or two programs? The pieces have to be representative, interesting, and show the company in the best possible light. It’s not easy, as the recent Lincoln Center performances of Australian Ballet have shown.

The company, under the direction of David McAllister, is marking its fiftieth anniversary season with a tour to New York that ends today (June 17), previewed by a performance by four of its best dancers at Fall For Dance last year. As McAllister says, touring is important for keeping the company’s standards and morale up: ”You push yourself a little further artistically, technically, in every way,” he recently told the journalist, Nick Miller. Because the Australians’ last visit here dates back to 1999 audiences were eager to see them, despite competition from American Ballet Theatre just across the way at the Met. Even so, the Koch Theatre, home of the New York City Ballet, seemed quite full, especially later in the week.

The Aussies brought two programs, one a kind of retrospective (“Infinity”) and the other a full-evening ballet: Graeme Murphy’s 2002 “Swan Lake,” which has met with enormous success in Australia and the UK. As Valerie Wilder, the company’s executive director, points out in a special tour program, all the ballets on show (except for the excerpts which were featured in the first part of “Infinity”) were commissioned by McAllister. Several (“Swan Lake,” “Waramuk,” “La Favorita”) were by Australian choreographers.

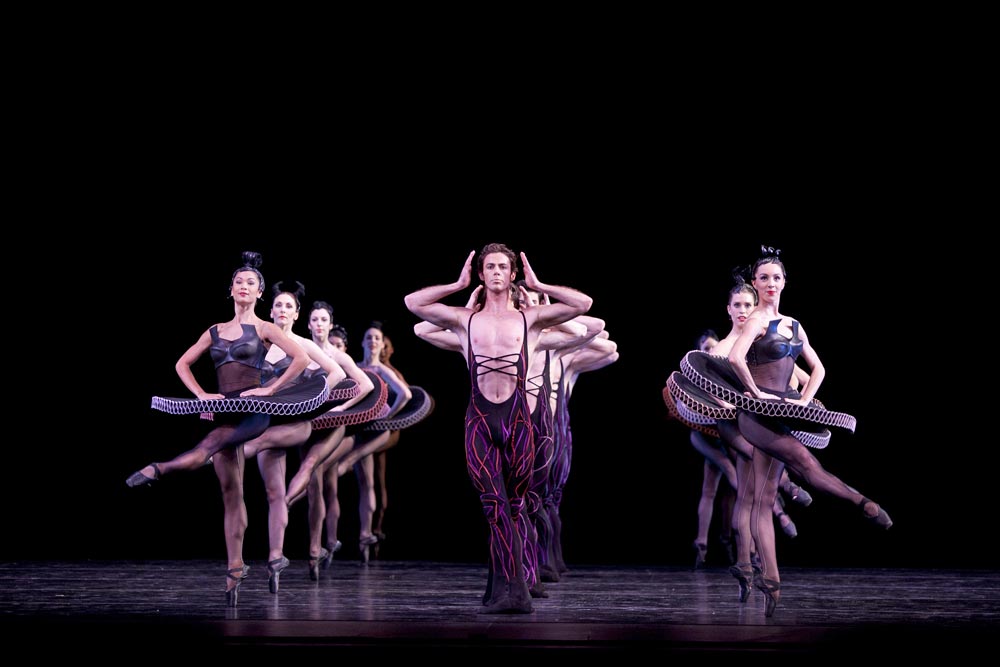

The overall impression was mixed. The good news is that the dancers are excellent: athletic, superbly trained, with lovely lines and crisp footwork, and an unmannered, open style. The bad news is that, for the most part, the repertory – at least what we saw here – was not on the same level. Take the retrospective: it began with a multimedia presentation, a combination of narrated film shorts of the company’s fifty-year history interspersed with pas de deux (from “Don Quixote,” “Giselle,” Petal Miller-Ashmole’s “La Favorita,” etc.). The film was warm, animated, full of pride, but the series of pas de deux didn’t add up to much: everything was well danced, but nothing stood out in particular. That is, except for the section of Stanton Welch’s “Divergence,” selected to represent the company’s coming of age. It was notable mainly for its ridiculous costumes – laceup leotards with bare chests worthy of Béjart’s kitschiest moments and stiff tutus with leather bras and headgear for the girls, except for the woman wearing fringed bell-bottoms. It’s difficult to judge what appears to be a particularly eccentric ballet from an excerpt, so I won’t, but as a closing number for a historical sampler it was certainly a head-scratcher.

Then came “Dyad 1929,” a piece made for the company in 2009 by the British it-choreographer Wayne McGregor. It looked like the other McGregor ballets I’ve seen – squiggly and stretchy, with lots of splits and awkward coordinations of the body, especially for the women, and little sense of momentum or coherent internal structure. It relied on the built-in pauses in Steve Reich’s “Double Sextet,” a lively, if repetitive piece of jazzy minimalism, for whatever shape it had, which made it rather less innovative than its technical complications seemed to imply. When the music slowed, dancers entered or exited, with studied nonchalance; when it became more lyrical and soft, McGregor created a pas de deux, etc. The best things about it were the designs, a continuous polka-dotted surface behind and underfoot and, as always, cool lighting effects (by Lucy Carter). The costumes, by Moritz Junge, were more flattering for the men than the women. The piece in no way reflected its supposed inspiration, the Ballets Russes, nor McGregor’s interest (described in the program) in Shackleton and Richard Evelyn Byrd’s explorations of the South Pole. Given the Ballets Russes theme (also mentioned in the film excerpts), it might have been more interesting to bring Alexei Ratmansky’s “Scuola di Ballo,” a riff on Massine which he made for the company in 2009.

The last work on the mixed bill was “Warumuk,” a collaboration with the Bangarra Dance Theatre, which specializes in fusing indigenous Australian stories, rituals, and movement with contemporary dance. The multi-part work by Stephen Page, director of Bangarra, draws on Aboriginal astronomy and creation stories, with elaborate and quite beautiful backdrops (evoking the night sky and Aboriginal art), body-paint and costumes, and a big, Hollywood-style score for orchestra laced with Dhuwa and Yirritja songs. The choreography creates some striking images, and the Australian Ballet dancers adapt themselves well to Page’s rolling, loping, grounded style, but in the end it feels superficial and packaged for export, mythology-light. The intentions are admirable, but it’s over-produced, over-Westernized, with big crashing crescendi and lots of unison movement. And it drags. One dancer, Waangenga Blanco of Bangarra, stood out for his intensity and the earthiness and sensuality of his movement.

After the mixed program came Graeme Murphy’s “Swan Lake.” The production, which has had wide success since its premiere in 2002, significantly alters the storyline: it begins, not with the prince’s birthday party, but with a sexy pas de deux between the prince and a temptress, which ends up in a bed (with black satin sheets). Cut to the prince’s wedding, in which he becomes hitched to a mousy girl (not the woman from the pas de deux) wearing a dress with a gigantic train that conceals her feet and hinders her movement. The temptress (Baroness von Rothbart) is a featured guest at the party, the bride (Odette) goes mad with jealousy and is carted away to the mental asylum, and the prince ends up back in the arms of his lover, watching the sunset over the lake. End of act one. Act two takes place in the asylum, where Odette dreams of swans and of her indifferent bridegroom, who now returns to her as a tender lover. (It’s not clear whether the prince actually comes to visit, or whether he too is a figment of her imagination.) And finally, in act three, Odette shows up uninvited at a party hosted by the prince and his grasping girlfriend and woos him back. He succumbs either out of guilt or because he now perceives her charms; it’s unclear. The baroness calls the ward, and Odette has another “episode.” The final scene is a dream sequence in which Odette, now in a black swan tutu, reconciles with the prince and then is swallowed up by the lake, as if disappearing into a black hole.

Murphy was reportedly inspired by the story of Prince Charles, Princess Diana, and Camilla Parker-Bowles (now the Duchess of Cornwall). But of course it’s a little far-fetched: Diana didn’t go crazy, Ms. Parker-Bowles is not a monster – in the final act, the Baroness repeatedly tries to throttle the prince, à la Fatal Attraction – , and Prince Charles isn’t half as dazed as this poor hapless prince, going back and forth between the two objects of his affection. But never mind. The first act, which is practically a complete ballet in itself, should be entitled “The Wedding from Hell.” Padded with music from the Tchaikovsky’s third and fourth acts, it includes a divertissement – a lively, crisply-danced czardas – several tortured pas de trois for Odette and Camilla (er, the Baroness) reminiscent of Antony Tudor’s “Lilac Garden,” and a mad scene straight out of “Giselle.” It even has a happy ending of sorts, as the prince and his adulterous lover gaze out over the lake. Like the actual Camilla and Charles, they seem to really like each other, while Odette comes across as a bit of a hysteric.

The sets and costumes for the first act are attractive, with an elegant Edwardian feel (long dresses, tails, lots of white, parasols, a pretty lake). The second act, at the asylum, is also striking, with a giant bathtub and network of pipes that disappear to reveal a white disk, the lake, covered in amorphous mounds that unfold into swan maidens. However, the patterns for the swans are less interesting than those in the original Ivanov choreography, the dancing less evocative of bird-like movement and less poetic. The pas de deux is dominated by acrobatic lifts, notably one in which the prince raises Odette by one leg and she bends forward in an arabesque penchée in the air, directly in front of the prince’s face. The problem with this kind of partnering is that one can see the two dancers preparing for the next big lift in advance; it breaks the flow and the storytelling in the dancing. Also, the prince – danced on the evening of June 16 by the tall, handsome Kevin Jackson – hardly gets to dance on his own, which is a shame. The party in the third act sets the stage for some bravura dancing for two dapper male guests (are they meant to be a couple?) and a cute, extremely athletic young couple. (Unfortunately, none of dancers in the secondary roles are identified in the program.) The dancing throughout was crisp and incisive. I particularly enjoyed the main czardas couple, also not named in the program. Madeleine Eastoe, as Odette, was slightly anonymous at first, completely overshadowed by the hungry, powerful dancing of Lucinda Dunn as the Baroness. But Eastoe came into her own later, it the lakeside scenes – her pliant body and expressive arms, especially, gave her dancing a touching vulnerability. Jackson had nice lines, and revealed himself to be an excellent partner. The fact that he didn’t seem to know whether he was coming or going half the time is the fault of the character as it has been defined by Murphy, not his.

Given Murphy’s reordering and repurposing of Tchaikovsky’s music – several climactic bits are repeated in different acts – the production feels strangely incoherent, especially if one knows the ballet already. A lot of music goes to waste, as background to Odette’s various psychotic episodes. But one can see the production’s appeal – nice designs, fresh ideas, sexy duets – and after all, there are a lot of not-great Swan Lakes out there. Somehow, no-one seems to mind.

Dear Marina,

This time there was more divergence in our opinions.

I attended Friday night’s performance of Giselle. {think you mean Swan Lake. Ed}

As usual, the music was beautiful.

I found that the first act had insufficient ballet and too much acting (some of which was absurd). I was almost ready to leave, but I decided to stay.

The dancing in Act 2 improved, was interesting, and caused me to decide to stay for Act 3. Again, I enjoyed the dancing much more than in Act 1.

I disliked the costumes in Act 1. I found the act quite disjointed.

I did not like the set for the lake, but I thought that the set for the ball was beautiful. The tub in Act 2 was unnecessary but did give the atmosphere of the asylum.

I am looking forward to seeing the more traditional Swan Lake of ABT.

I think that you have a great job!!

Best,

Barbara

Thank goodness for differences of opinion, otherwise what a boring life we’d have! Thanks for your comment and point of view.

Cheers,

M