The Royal Ballet

The Prince of the Pagodas

London, Royal Opera House

2 June 2012

Gallery of 27 pictures by Dave Morgan

First Night Curtain Call gallery by Dave Morgan

www.roh.org.uk

Received wisdom insists that The Prince of the Pagodas, like Ondine, must remain in the Royal Ballet repertoire because of their scores, commissioned from admired 20th century composers. The ballets, by Kenneth MacMillan (after John Cranko), and Frederick Ashton, the company’s leading choreographers, ought surely to be treasures.

It shouldn’t matter that their fairytale scenarios are unsatisfactory. So are those of most 19th century ballets, which doesn’t stop us enjoying their craftsmanship. But what makes a ballet endure is its music. If it is truly ‘dansant’, steps and music coalesce, forming an emulsion like mayonnaise. Petipa achieved it with Tchaikovsky, Balanchine with Stravinsky. It’s debatable, however, whether Ashton really gelled with Hans Werner Henze, or Cranko and MacMillan with Benjamin Britten.

Yet both composers collaborated closely with their choreographers, working to detailed minutages – the timings and placings of scenes, solos, duets and ensembles. Henze wrote a fascinating account of his work in progress (published by Dance Books as Ondine: diary of a ballet), asking himself questions such as: “How can I live up to the task that I have been set without compromising on the technical standards of ‘new music’? Is it even worthwhile to introduce complicated elements into ballet music, which will neither be heard nor contribute to the clarity of the action on stage? Should I not completely sacrifice my emotions for the sake of providing opportuinities for the great ballerinas to jump, run, turn and express themselves on stage?” Read his reflections and you would assume Ondine had to be a masterpiece. Britten, less forthcoming about his only full-length ballet score, might have hoped The Prince of the Pagodas would be a modern equivalent of The Sleeping Beauty.

In the end, the scores are to blame. Tantalisingly, they are not ballet music. As far as I am aware, no choreographer has succeeded in making a classic Ondine or Pagodas. (David Bintley’s Prince of the Pagodas, created for the National Ballet of Japan, is to be performed by Birmingham Royal Ballet in 2014, so perhaps his may be the exception.) Yes, there are motifs for the main characters, descriptive passages and spirited numbers for ensembles, but every time anything infectiously ‘dansant’ gets going, it’s subverted by changes of tempi, rhythmic displacements, dissonances and other ‘complicated elements’. Pity the poor dancers, trying to keep track of their counts; pity the audience members longing for a tune to hang onto and a rousing resolution instead of a sudden halt.

I suspect the problem with Pagodas is that Britten was composing a sound world contrasting two cultures which are then reconciled – occidental and oriental. But that doesn’t happen in the ballet, either in Cranko’s or MacMillan’s scenario (prepared for him by Colin Thubron). There is no kingdom of the pagodas – just a salamander. In the latest version, the eponymous prince appears to be an amiable bloke betrothed to Princess Rose: is he a resident courtier? visiting royalty – from where? Metamorphosed into a salamander, he is seen briefly against pagodas, accompanied by Indonesian gamelan gongs; once transformed back into a bloke, there is no longer any oriental element about him, except mysteriously in the music.

In this revival of MacMillan’s 1989 ballet, staged by Monica Mason and notator Grant Coyle, with the co-operation of Deborah MacMillan, Barry Wordsworth and Colin Matthews of the Britten Estate, about 20 minutes has been cut and the order of events altered in order to strengthen the dramatic storyline. Instead of opening with a prologue in which the doddery Emperor divides his kingdom, Lear-like, we meet Princess Rose playing blindfold games with the court Fool and her fiancé, in a plum-coloured jacket. They seem a happy enough couple until the Emperor arrives and upsets Princess Épine by allotting her the smaller half of the empire. She curses Rose by turning the prince, in a flash, into a green lizard. Cue the salamander theme, but no music for Rose (or anyone else) to react to this transformation.

In the next scene, the courtiers, wearing monkey masks above their Tudor ruffs, gibber like a troupe of baboons. Épine takes command, usurping her father, as four kings arrive. They don’t appear at all disturbed by the simian court or the Emperor’s senility. Each king has his own musical variation, cleverly differentiated by Britten. Épine and Rose both have contrasting solos, Rose to a wistful oboe and harp. Her frozen pose and a far-off fanfare indicate that she experiences a vision of her missing fiancé, with whom she dances ecstatically. After that, she understandably rejects the four kings. Épine takes them on in a parody of the Rose Adagio. She is Rose’s evil twin, sexually available in a way that her younger half-sister is not.

Épine, like Carabosse, rivals the magical power of the Fool, Rose’s Lilac Fairy. Épine remains awake on the Emperor’s throne while the Fool puts the court to sleep and takes Rose on a journey to find the enchanted prince. In MacMillan’s ballet, the journey is supposedly into the young princess’s subconscious. But Britten had provided masses of music for Cranko’s 1957 version, in which Belle Rose encountered clouds, stars, flames and sea creatures before reaching the Land of the Pagodas. Much of that music is now cut, except for passages allotted to nightmare visions of the four kings. Though they retain their physical characteristics, more threatening than in Act I, they’ve lost their musical identities. (In the 1957 ballet, they disappeared after Act I.) They represent various aspects of masculinity, with the macho King of the South the most repellent and dangerously attractive to Rose. The Fool banishes them, leaving Rose alone for a lovely solo to a violin. She puts her hand to her temple, parted fingers drawing attention to her eye – her insight – as she darts in bewildered changes of direction and swirls in pirouettes.

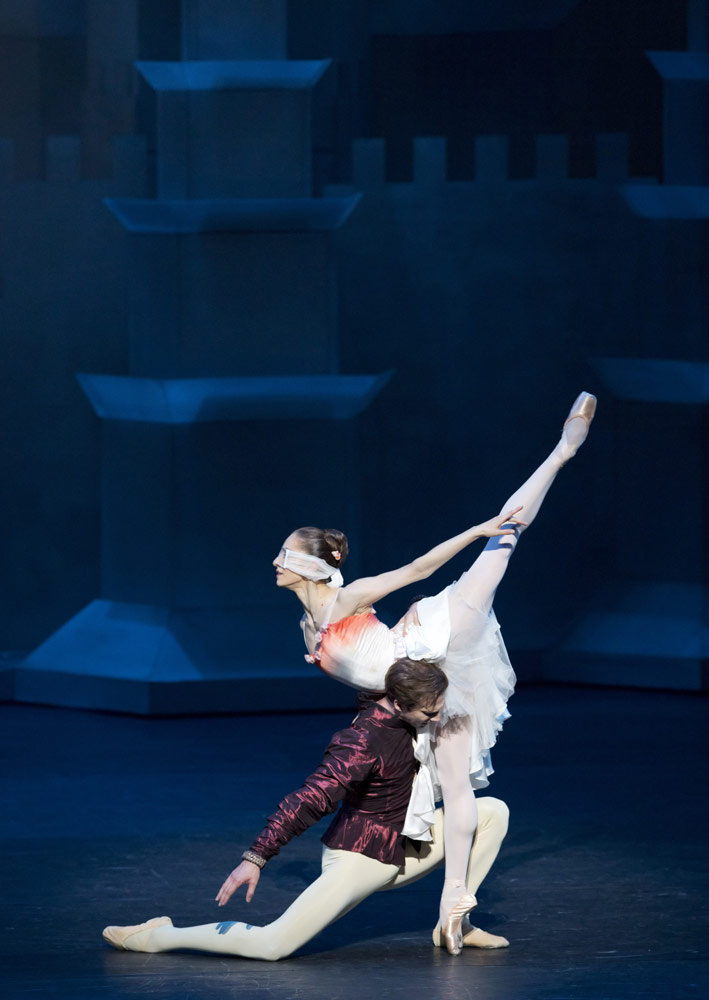

The Fool leads her through a shifting maze of castles (why not pagodas?), while Britten’s transcription of a gamelam orchestra summons up the salamander, spotlit in lime green. The Fool, after bounding in a solo like the Monkey King of oriental epics, blindfolds Rose for her encounter with her transformed fiancé. She imagines him as the prince she loved as they dance an Orpheus and Eurydice pas de deux. She is eager, curious, exploring her feelings for him without being able to ‘see’ him: he winds her around his body, supporting her on his back rather than facing her. He enables her to fly, to poise off-balance, to be fully herself without sexual possession. He kisses her and vanishes, to reappear as the salamander. She and we understand that he hates his scaly condition. She embraces him compassionately, maternal and virginal.

By omitting the corps de ballet and demi-soloists who were clouds or stars in MacMillan’s 1989 version (but keeping the running banners), Act II is much shorter and better focused. It no longer recalls the vision scenes of 19th century ballets, but parallels with The Sleeping Beauty don’t have to be laboriously drawn out.

Act III has been radically re-arranged so that the Grand Adagio by the betrothed couple follows the conventional sequence of pas de deux, male variation, female variation and coda, instead of being interrupted. The order of events is now much clearer. Evil Épine rules the bestial court; the four kings are her suitors; the Emperor is in a bad way in his golden wheelchair. Rose, summoned by the Fool, comforts her father and the salamander, who is swiftly transformed back into his plum jacket as the prince. He then fights and overcomes the kings with weapons provided by the Fool, who restores the crown to the Emperor. Rose, however, does not witness any of this and nor does the court – they’re offstage, changing their costumes. Épine is present until, inexplicably, she vanishes, never to be seen again.

The courtiers return in pink and gold satin and fuzzy wigs to dance a volta of rejoicing. The castles of the set part to reveal gleaming pagodas in the background: two kingdoms, ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’ are united in the pas de dux that follows to gorgeous, lush music. There are references to The Sleeping Beauty’s wedding pas de deux, with additional flourishes. Rather than being grandly formal, the dancing is bold, joyous, jocund – and incredibly taxing. The corps de ballet finally get a chance to dance neo-classically in a Grand Pas d’Action before a mad high-kicking finale, as the Fool unites the happy pair’s hands in marriage.

Back to the Ondine problem: the promise of a magical ballet is never quite fulfilled. Britten’s score, like Henze’s, is not compensation enough for the lack of psychological motivation in the story. You cannot see the music in the choreography, inspired though it sometimes may be. In The Prince of the Pagoda’s opening cast, Marianela Nuñez was a confident, radiant Rose, blithely disregarding the difficulties in the partnering, in which she was ably assisted by Nehemiah Kish. Nunez, less athletic-looking than Darcey Bussell in the role, was a more conventional heroine: a Cinderella who blossomed in love and compassion rather than an adventurous youngster as yet unaware of her potency. What a wonderfully secure technique Nunez has – a true Aurora. Kish finally became interesting as the suffering salamander; as the prince, he didn’t deserve Nunez’s ardour. Alexander Campbell as the Fool managed his virtuoso capers well, often dominating the stage on his own. It’s a big role, as is that of the Emperor, whose plight dictates the story. Alastair Marriott made him a petulant dotard, unsympathetic in his loss of status until he shame-facedly had to crave his youngest daughter’s pity. Tamara Rojo was a sultry, dark-hearted villainess, miscast in a role that requires triumphant leaps. Among the quartet of Kings, Steven McRae was outstanding as the King of West, viciously decadent. Barry Wordsworth conducted the trimmed and re-ordered score as though it were great ballet music. If only.

Fascinating. This is the sort of writing that makes one glad for the existence of web-based dance criticism, giving space for a proper consideration of the work as opposed to a few lines in a daily paper.

This was really helpful and now I can understand this ballet much better. I saw the performance on the 6th June and came out feeling inadequate and baffled.

I would not see it again, as the music was so difficult and I was unable to hold on to at least a few notes. But this review is so through that I am feeling much better. Thank you.

Thanks to Jann Parry for a fascinating dissection of The Prince of the Pagodas.

I think though there is more of a problem than just the score. The comparison with Ondine is not completely congruous. With Ondine – in the theatre – music and choreography mesh to form a work that has its own theatrical propulsion. Only on reflection do holes appear in dramatic logic or characters’ motivation.

That the score for Pagodas can be trimmed and reordered reveals how episodic it is. There is no overarching symphonic arch that carries the narrative. As Jann Parry rightly says, it is not dansant. Nor are many individual numbers which evaporate musically without reaching a theatrical climax. In particular, the opening section of the duet for Rose and the prince in act three, with its gorgeous, plangent tune, just fizzles out.

As danced in its first season in 1990, MacMillan’s ballet was a glittering visualisation of Britten’s shimmering score. It was not so well danced on its last outing in 1996. Ballet and score appeared the poorer. That seems to have prompted a decision to tinker.

This filleted Pagodas aims for drama rather than fairytale. Without the fairytale framework – those clouds and waves that establish a romantic world (in the Shakespearean sense) where dramatic illogicalities are strangely logical – now the dramatic motivation of Pagodas is even thinner. The reordered first act does not clarify the reasons why but makes the action more unmotivated.

Without the divertissements more emphasis is placed on the story – but there is not enough of it to fill three acts. Music and choreography are not working together. The closing divertissement looks like a hangover from another ballet. We are a long way from MacMillan’s intended homage to classical ballet.

Even without the cuts, we are also a long way from hearing the orchestral textures and colours of Britten’s score. The conducting was lugubriously emphatic, the orchestra unremittingly loud.

The Prince of the Pagodas is still a problem child – and a better ballet yet than this.