Emery LeCrone website: emerylecrone.com

At 25, Emery LeCrone has an impressive resume. The native North Carolinian has been choreographing for less than ten years but she has already created new works for a long list of institutions and in a wide variety of contexts. Aside being commissioned to create works for Colorado Ballet, Oregon Ballet Theater and North Carolina Dance Theater, among others, she is also resident choreographer at both New Chamber Ballet and the Columbia Ballet Collaborative, two much beloved boutique troupes in New York. In 2011 she was also commissioned by the Guggenheim Museum to make a dance to the music of Elliot Carter for the museum’s Works & Process Series. Last year she was invited to the New York City Ballet’s New York Choreographic Institute. In 2011-2012 she was one of three artists invited to the inaugural New York City Center Choreography Fellowship Program, an award that gives choreographers a stipend and free rehearsal space. In her free time she teaches classes and workshops. She also produces an annual performance series called the Young Choreographer’s Showcase. All that and she still dances too!

It’s a rapid career launch for a dancer who came to New York City five years ago to do a workshop with Complexions Ballet and decided to stay. But that’s Emery. Equal parts free spirit and self-disciplinarian, LeCrone manages to make the creative life look easy. Tall, thin with long brown hair, LeCrone is always dressed in a way that makes one suspect she employs a very tasteful professional stylist. Despite her busy schedule she usually seems relaxed, and stops to talk whenever she spots a friend. She lives with her somewhat incongruously named Rat Terrier, Sophie.

In the coming year LeCrone will be working with students at Juilliard and the University of North Carolina School of the Arts. Both groups of dancers will be great for LeCrone’s work, which is balletic with a modern dance weightedness. Unlike other choreographers working in similar idiom, LeCrone uses movement to create shape, not simply articulation. Five Songs for Piano, a women’s dance set to Mendelsohn, which LeCrone created for the Columbia Ballet Collaborative, is a good example of the way she can layer lyricism, angularity, and emotion. Her recent studio showing at New York City Center included a men’s piece that demonstrated the same sensibility, but on a bigger scale.

LeCrone had some time last week before she headed to a meeting at the Metropolitan Opera House. We sat down and talked about her career, her inspirations, and her take on the latest dance television programming.

—oOo—

NA: In addition to all of your work as a choreographer, you also work as a dancer at the Met. How do you find a balance between the two?

EL: Well I think for right now it’s really important for me to do both, because being a dancer reminds you of what it feels like to be in the studio working with choreographers, to be on the other side of that, and vice versa. I think it’s good to remember sometimes what it’s like to be rehearsing and to be dancing all day long. So for me I feel like I’m in a really good place where getting to go between the two [dancing and choreographing] actually really benefits the work.

So as a choreographer, and I suppose as a dancer, who are your influences? Whose work do you really like?

I’m influenced by a lot of different things. Not just other choreographers, and it changes all the time. But specific choreographers – I think the people who have influenced my generation, or maybe my work, obviously George Balanchine, Christopher Wheeldon, Ratmansky, Benjamin Millepied, a lot of the prominent classical or ballet-based choreographers I guess that are evolving the technique. But I also love more contemporary choreographers, including Pina Bausch. Crystal Pite I enjoy. I think there’s a lot of great artists out there who are making good work.

One of your projects is the Young Choreographer’s Showcase. Can you tell me more about your vision for that?

We’ve had two seasons of it. When I started the vision was really that I had very close friends – Justin Peck, Avi Scher, Jon Malik – that were all in my age range that were all creating new work, mostly with classically trained dancers. And so it just seemed natural. You know I kept going to all their shows and they kept coming to all mine, and eventually we all just decided ‘why don’t we put on a show together?’ I guess I sort of headed that up. Got everybody together, and it was great.

And then last year it evolved. The goal is to have new choreographers each year, so I invited a couple of choreographers from ABT, including Nicola Curry. And then I also invited Kimi Nikaidoh from CBC [Columbia Ballet Collaborative]. So whereas the first year I was the only woman, this last year I had three women and two men choreographing. So it was a nice mix. And there was a lot more work on flat. Still classically based, but Nicola’s was more contemporary.

You’ve done work with professional companies, and CBC, and Juilliard. You’ve done work on pointe and on flat, in a variety of contexts. So, what do you look for in a dancer?

Well I think the most important thing is someone that’s really just open to ideas and collaboration and exploration. Actually in some ways working with students is a little bit easier than working with professionals. I think because they have the basic training but they are very hungry, and they’re a little less experienced. So it’s more of a canvas in which to draw the work. And working with professionals, I think it has to be a lot more collaborative and that professional has to know what their particular strengths and weaknesses are, as do I; and then we have to develop a conversation, about the work and through the work, I think.

Tell me a little bit about your choreographic process. Say that you’re starting with the open, open-minded dancer.

Well it really depends on the piece that I’m working on at that time. Most of the time I’ll come in with a little bit of phrase-work prepared and start teaching that. It might be to different sections of music, or you know the music might have already been picked out for me ahead of time. But I’ll come in and start to teach the steps and then really work with the dancer on what parts are working for their body and what parts aren’t working and how to make it a little bit more comfortable or organic.

And in terms of music?

When I worked at the Guggenheim it was a piece by Elliot Carter, and they had preselected it for us. So for that I actually really had to stick with the score and choreograph pretty directly to it. But generally I like to play a lot of different things – songs, music, scores, whatever – that change the dynamic of the movement and then see how the dancer reacts or relates to that change in tempo or change in feeling, through the phrase-work.

So it’s very much an ad hoc, well maybe experimental process?

Yeah, you could say that – at first. I mean, again, it depends on what that particular process is. Like the Guggenheim. I had steps, and I had counts, and there was sort of more of a structure from the very beginning, and I think that’s one way of working. But there’s another way that I often use where you let it be more free in the beginning, and then as the work develops you add structure over time.

A year ago you and I had a conversation in which you told me you’re really enjoying being in New York and just sort of “playing.” So is that still the case, and what exactly did you mean by that?

I said I was in New York and enjoying freelancing?

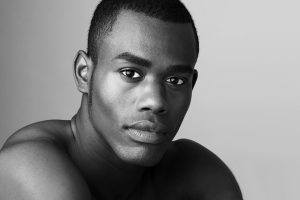

You said you were happy being in New York, working with different types of dancers. At the time you were working on a solo for Richard Isaac for the Columbia Ballet Collaborative performance.

I think with Richard that word [‘playing’] definitely makes sense because we’ve worked together for a long time. And we’re very close friends as well, so for that particular process I felt very comfortable to include a little more improvisation and freedom for him to develop ides and for myself to develop ideas. And yes, I think that’s incredibly important.

As far as working in New York, I love working here but it’s so important to keep travelling and to keep working with different companies. The Juilliard School is a great opportunity, and I’m very excited about that. But I think it’s important to keep going to different organizations.

In the practical sense, in terms of establishing contacts or…

Or just working with different companies… Each company, across the country really has a different physical aesthetic and approach to their movement. Their repertories are different, whether it’s more classical or more contemporary. So every time I go to a different company I learn a little bit more about how I need to adjust to that company’s vocabulary. And that I think is really beneficial because it makes you more versatile. It makes the next time you go to a school a little bit easier, the next time you get a larger commission, you know from a more classical company, a little bit more accessible.

Makes sense. So, silly question: Have you been watching Breaking Pointe?

[laughs]I did, I saw the first episode.What did you think?

I actually enjoyed the first episode a lot. I loved it.

There is a lot of truth, and I was actually impressed by how much ballet they showed in the first episode – the actual rehearsal process and little parts of variations. I love that, because I think we get often a glamorized, Hollywood version of what dancing is like. You never see the practice clothes and the sweating and the corrections and the things that really go on.

I’ve heard that since the first episode, in either the second or the third episode there’s a scene where one of the dancers is in rehearsal just getting correction after correction after correction. How she has a really real moment where she just can’t get it. She knows the correction, but her body is not doing it, and I think that having that side of dance portrayed on TV is great. People don’t realize how much hard work it is.

Yeah, and that’s Elena Kunikova in that episode.

Oh yeah, yeah, yeah.

You did the inaugural season of the NYCC artist fellowship. How important was that for you?

That was amazing. And it’s still happening until this October. It was a huge honor. Andrea Miller and Shen Wei, the other choreographers, are very successful and well-known. I’ve been watching their work for several years now. I actually remember going to a Joyce Soho studio showing a few years ago where Andrea Miller was premiering, I think Blush was the piece, one of her first blockbusters, and being blown away by her work. So to be included in this with them is really a surprise, and a huge honor.

Do you feel like a ballet choreographer? Or a choreographer?

I feel like just a choreographer. I think the difference between Shen Wei, Andrea and myself is . . . obviously Andrea trained with Batsheva and attended the Juilliard School so her training is modern, contemporary based. Whereas I attended summers at SAB and danced at North Carolina Dance Theater with Patricia McBride and Jean Pierre Bonnefoux. So we just come from different places. But I don’t consider myself strictly a ballet choreographer or a modern choreographer really.

Last Question – What makes a great ballet?

For me, what really makes a great work (read for me) is when I feel like all the elements are coming together to one truth. When I feel like there’s a harmony between the music, the movement, the costumes, the lighting design, and the dancers. I think you can have great steps but have a costume design that completely distracts me or vice versa. So what I look for in my work is sort of finding a balance between all these different elements.

Emery LeCrone is planning another studio showing at New York City Center for the fall. Her work for Juilliard will be performed December 12th – 16th.

You must be logged in to post a comment.