© Maarten Vanden Abeele. (Click image for larger version)

Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch

World Cities 2012: Wiesenland

London, Sadler’s Wells

8 July 2012

www.pina-bausch.de

Tour blog

World Cities 2012 details

DanceTabs reviews of World Cities 2012 performances

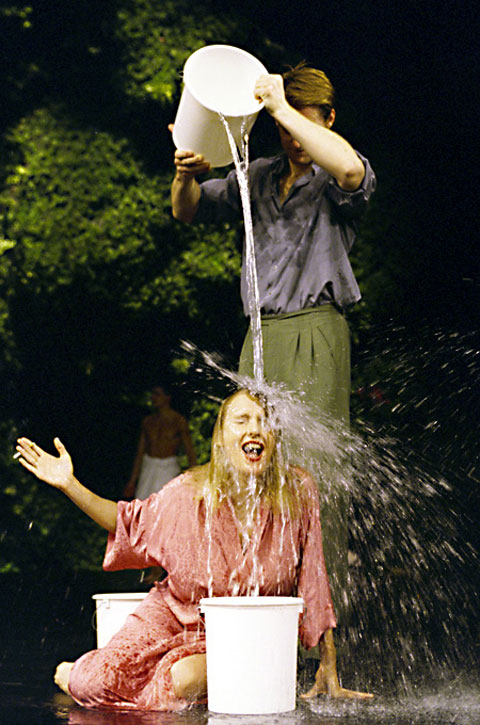

Outside the stage door entrance to Sadler’s Wells loomed a vast rain puddle, waiting for the wheels of passing buses to soak smokers standing on the pavement. Members of Pina Bausch’s company were having a last drag off-stage before being drenched as they smoked onstage in Wiesenland.

If Bausch had been alive (if only) to create a Pina piece about the London season, it would surely have reflected the wettest of all her company’s residencies. Forget other cities bisected by rivers – Budapest, Istanbul, Rome – the whole of London was awash with water throughout the five-week run.

Look at the company’s London blog, with photos taken by cast and staff members and see how eccentric the city looks: blog.pina-bausch.de/wordpress. The snapshots illustrate how each of the city residencies must have fed into the final productions: sly observations, bizarre encounters, unpredictable reactions. ‘We do not describe a city’, Bausch is quoted as saying. ‘We describe the feelings we have picked up there.’

That’s the dilemma for (some of) us spectators. I can’t help seeking clues about the surreal incidents in each piece: did this or that actually happen? or are we witnessing the typical behaviour of personalities in the cast? How is it that every production, whatever its origin, belongs so recognisably in Bausch’s world view? If someone takes over a role, do they repeat the original actions or bring their own interpretation? Do such questions really matter?

© Laszlo Szito. (Click image for larger version)

The answer must be no. We can’t tell which episodes may have been culled from experiences on location; obvious references to another country’s culture tend to be ironically touristy rather than insightful; the rural sets bear little resemblance to the sprawling cities that presumably inspired them. That said, there is a clue to Wiesenland’s verdant setting in a photo on the blog. Visiting Budapest in 2000, company members went to a restaurant where a Hungarian gypsy band was playing. Occupying one wall was a painting (or photograph) of a lush forest and a waterfall.

For Wiesenland (German for meadowland), the back wall of the Wells stage sprouted mossy green foliage gently trickling into a trough at the base. Dancers bathed in the water and mopped themselves and the floor with towels. Budapest is a city – two cities bordering the Danube – of hot springs, Turkish baths and spas. In a spectacular theatrical effect at the end of the first half, the greensward tilted and descended, becoming a hillside park for trysts and picnics in the second half. As Eddie Martinez commented, conducting a lilting line of dancing couples, ‘Lovely, simply lovely’.

The audience was included in the loveliness. Smiling Regina Advento questioned the front rows, in mime, about their marital status and amorous relationships. Aida Vainieri and Jorge Puerta Armenta invaded the stalls in the heat of mutual passion before rushing back up the hill to consummate it out of sight. After witnessing a feast on stage, famished spectators were bombarded with bread rolls. Rare indeed is a Bausch piece in which the fourth wall isn’t breached by the performers.

Deceptively, over the season, we felt as though we had got to know some members of the company more than others. Their characters, assumed or innate, became familiar with repetition, as did their preferred ways of moving in solos. In Wiesenland, short Aida Vainieri with her wild mop of hair was the comedian, tall Helena Pikon the talker, Barbara Kaufmann the beauty, Rainer Behr the show-off, Fernando Suels Mendoza and Pablo Aran Gimeno the charmers. Andrey Berezin has taken on the disconcerting sort of roles Jan Minarik used to perform: here, the creepily courteous escort, the chicken minder and boat builder.

There were mad, wonderful vignettes in Wiesenland, involving props no sooner assembled than dismantled: the coop for live chickens, a precarious tower of chairs, a formal restaurant set-up, an informal stri-fry on a tiny stove, slapstick with furniture, pillows, towels. If there was a theme, maybe it was fecundity – of imagination, romance and sensuality, in an atmosphere less melancholy than usual. (The music, as usual, was an eclectic selection that bore little connection to the host city.)

I wondered whether the ritual, repeated at the end, of women puffing on cigarettes while being doused by the men with buckets of water referred to steam rising from thermal baths in Budapest or simply to safety regulations in theatres. Water plays a significant role in most Bausch pieces, as a symbolic element or because it was readily to hand in rehearsals, carried around by thirsty dancers in plastic bottles. Vital for life and purity, water is unpleasant and threatening in excess, as we know this summer. Perhaps Andrey Berezin’s wooden boat, under construction on top of the mossy mound, was after all an ark, holding the hope of salvation from the hot springs of hell.

I’m sorry, it’s not possible (as Julie Shanahan apologised in Agua) to make sense of a Bausch dreamland. Or to describe the feelings you have picked up en route. You either resist or give in, enjoying each scene, each dancer, each moment, without trying to assess their place in her enigmatic scheme of things. A French academic author, Brigitte Gauthier, set out to analyse Bausch’s choreographic language in detail (1) instead of describing what happens in each work. Not possible on the page. You can only experience it for yourself.

1. Le Langage chorégraphique de Pina Bausch by Brigitte Gauthier, publ. L’Arche

You must be logged in to post a comment.