© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

www.justin-peck.com

www.nycballet.com

Waiting for the Gates to Open:

A Young Choreographer Gets his Break

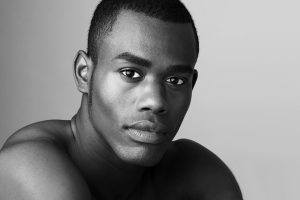

I met with the young dancer and choreographer, Justin Peck, the other day at Ed’s Chowder House, a discreet spot with decent lobster rolls (and wicked drinks) tucked into the second floor of the Empire Hotel, across from Lincoln Center. Peck, a corps dancer at New York City Ballet since 2006, is a familiar, reassuring presence onstage, often tapped for his confident partnering. He dances roles like Ivan in Firebird, the cavalier in Concerto Barocco and Midsummer Night’s Dream, the husband in La Sonnambula, as well as Janus in Robbins’ Four Seasons and the leader of a pack of running boys in Glass Pieces.

More recently, he has begun to choreograph. He made his first dance, a pas de deux called “A Teacup Plunge,” for the student-run Columbia Ballet Collaborative in 2009. This past year has been a particularly eventful one for Peck. His In Creases was premièred by NYCB at Saratoga Springs – where the company has a yearly run – in July, and he has an even bigger opening coming up: Year of the Rabbit, a ballet for eighteen dancers opening in New York (at the Koch Theatre) on October 5. It will be included on a twenty-first-century bill alongside works by Benjamin Millepied and Christopher Wheeldon. For the occasion, the company has commissioned a score from Sufjan Stevens, a kind of neo-folk-alt-classical composer whose compositional style combines melifluous melodies, satisfying counterpoint, and a strong rhythmic element (often involving complex counts and syncopations). Peck’s ballet is an expansion of of an earlier piece, Tales of a Chinese Zodiac, which he made for the tenth anniversary of the New York Choreographic Institute back in 2010. What immediately came through was an ability to create complex, shifting structures that were constantly engaging to the eye, but also balanced and, somehow, logical. It too was set to music by Stevens, a suite for string quartet entitled Run Rabbit Run which has now been expanded for string orchestra by Stevens, with the help of band-member, Michael Atkinson.

A more typical twenty-five year old might be losing his mind with stress at the prospect of such a high-profile début, but Peck is surprisingly poised and self-assured, though not in a cocky way. It’s just that he seems to know what he thinks about things and what he wants from himself and his collaborators; one can imagine that he inspires confidence in his fellow dancers, many of whom he has known since he was a teenager at the School of American Ballet. After our lunch, as I ran through our conversation in my mind on the way home, another quality rose to the surface: a certain fastidiousness, combined with kind of steely determination. Not bad qualities in a choreographer.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

I saw a performance of ABT in Giselle when I was thirteen. It was kind of a fluke, because they never toured to San Diego. But they came for a week and did Giselle. I saw Ethan Stiefel and Marcelo Gomes and Herman Cornejo. I had done a little bit of tap and musical theatre because my family used to vacation every year in New York. That’s where my interest in the city comes from. They would take us to see shows, and I saw Savion Glover, and that inspired an interest in tap. So I started with that. And then I saw how powerful male ballet dancers could be from the experience of seeing Giselle. I was a supernumerary in the production, one of the dog minders. I would watch from the wings, and during the second act I would go out front. So I got to see a couple of casts.

Was there a dancer that you particularly identified with?

I think Ethan Stiefel… but they were all good. Marcelo and Herman were up-and-coming then. They did the peasant pas de deux. But I remember both of them really distinctively. Julie Kent was Giselle. At that point, I started training pretty rigorously, at California Ballet.

Was it easy for you?

Not at all. I don’t know if it’s because I started late, or because I’m not naturally built for dance, but it was very hard, especially turnout and extension. Two years later I came to School of American Ballet. I came for the summer program and was invited to stay year-round.

Why SAB?

I think I just wanted to move to New York. Southern California seemed really devoid of culture. Its really outdoorsy, beach-focused. It’s nice to go and visit once in a while, but this feels like more of a fit for me.

Do you have a background in music?

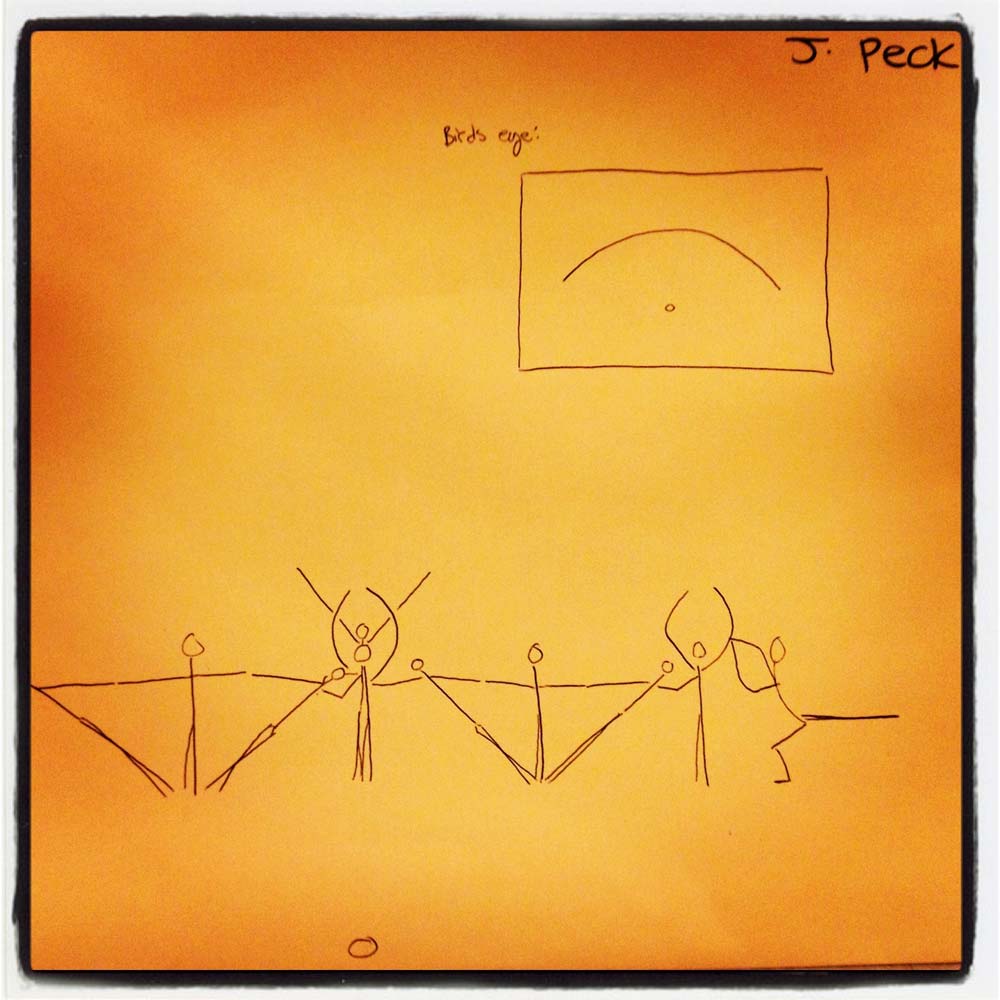

I studied piano at the School of American Ballet. I came when I was fifteen and started at the intermediate level. At that level you’re required to take music classes. It’s a great program. It was one of the best things about SAB and it’s the only level where it is offered. You don’t get to experience that unless you start at the intermediate level. I worked with a teacher there, Jeffrey Middleton, and then afterwards I continued for two more years, working privately with him. Eventually things got so busy when I became an apprentice [in 2006] that I had to stop. But when I started to get interested in choreography, I would look through the scores of music I wanted to use, and I found it to be really helpful. It really unveils details that you might not pick up on from just listening. I mark certain things in the score, and I draw a lot of structural images, sketches. It helps me to organize my outlook on what I’m going to do, if I have it all written down. It’s comforting to have a blueprint before I get into the studio.

© Justin Peck. (Click image for larger version)

How do you come up with ideas for movement?

I spend a lot of time in the studio improvising and using my own body as an instrument. I try to put a lot of thought into individual movement before I start working with the dancers, because time is so limited. So, I always try to come into the studio as prepared as possible. Usually I spend a couple of hours by myself in the studio before I get to work with the dancers. Then there is an element of improvisation, because you’re working with a living being with a mind of his own. So you come to a meeting-point in terms of how a movement is expressed, and it becomes something greater than what I could have come up with on my own. It’s a specific kind of chemistry that occurs in the studio, and it’s really thrilling, actually. It always ends up being something different than what I imagined.

A lot of younger choreographers seem to use quite a bit of improvisation.

I’m more of a micromanager; it works better for me. I like to have a lot more control over the outcome. I’m really interested in structure. And I don’t think there’s any shame in being prepared. I’ve read a lot of interviews where choreographers talk about how they go into the studio without any ideas and improvise, and something great comes out of it. There’s something about that I don’t buy. I guess I try to think about choreographing the way an architect builds a structure. An architect doesn’t just go out and start nailing two-by-fours together randomly. I like to have a blueprint and build up from that.

It’s not really a fashionable way to work.

Yeah, it’s not really cool. But it’s such a high-maintenance art form, it’s almost irrational not to work that way. It takes so much money and so much effort to make a ballet, that I don’t want to take any chances. Maybe it’s playing it a little bit safe, but I don’t know…

Have you been influenced in your way of working by your experience with other choreographers?

I’ve been most taken by working with choreographers who have genuine vision. The ones where you get into the studio and you can immediately tell they know what they want and what they’re doing. I think it’s respectful of the dancers to work in that way. It’s something I really see in Chris Wheeldon and Alexei Ratmansky. I think Ratmansky was especially influential on my working process, specifically the experience of working on Namouna [made for NYCB in 2010]. It had such a large cast, and he knew exactly what he wanted. He thinks a lot about the music and how he wants the choreography to relate to the music. I think that’s something I picked up on.

He’s also a serious student of ballet history.

I’m probably not nearly as geeky as him about that.

Has he mentored you?

A little bit. He’ll email me whenever something big comes around, but he’s so busy, I don’t understand how he’s able to function at the level he functions and be nice and be talented and produce great work with the amount of commissions he’s taken up. I feel almost lucky that I’m still dancing because in a way it limits my output and gives me a chance to really focus on select commissions.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Would you say that dancing Balanchine has had a big influence on you as a choreographer?

I learned the most from his work, especially with regards to structure. I think it would be such a sad art form without Balanchine. If Balanchine had never existed, I don’t know if I would have wanted to choreograph. At SAB they have this great program where they give students free tickets every night; I would go every night and see nearly every performance, and it had a really profound effect on me. I think it’s the reason I wanted to devote myself to ballet. When I first came to SAB, it was sort of my excuse to run away to NY. The experience I had there really changed me.

Tell me about In Creases, your first work for New York City Ballet.

It premiered at the gala in Saratoga [where NYCB has a summer season], and then the company took it on tour with the Moves group this summer. [New York City Ballet Moves is a small touring ensemble of NYCB dancers.] I think that was the idea behind Peter Martins asking me to expand the work, which I started at the New York Choreographic Institute. On the tour, I danced in In the Night and Moves – both by Robbins – and The Waltz Project [a series of pas de deux by Martins]. I would go out front with all my makeup to watch the dancers perform my ballet and then run back and warm up really quickly and perform.

Link: Alastair Macaulay’s review of In Creases for the New York Times.

How much time did you have to make In Creases?

I was freaking out a little bit because I was used to the Institute where you know exactly how much time you’re going to get, but at City Ballet it’s whatever they give you, and there’s not a lot of communication. You get a schedule with two days at a time and that’s what it is. I might get two hours one day with the whole cast, and then the next day I would get a half hour with one dancer, and the next day nothing. So it was hard to build momentum. We only finished it a couple of days before the premiere, and I had moments when I had to beg for one more rehearsal. It’s probably one of the reasons why I’ve taken on this way of working where I think a lot about what I want to do before I get into the studio.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

How did you adapt In Creases for the company?

It was made longer, and certain concepts were changed. And then you add the element of costumes and lighting. There was no budget for costumes, so I went to the City Ballet warehouse and looked at everything and tried to find something I could recycle or re-use. It was difficult, because everything looked either very dated or too current, and you could sort of recognize what ballet it came from. Luckily we found something that worked: there was a ballet a few years ago by Peter Martins called Friandises, and the costumes for that were very basic. We took the leotards, basic Yumiko style leotards, and removed the skirts, and then we got these reject unitards and chopped them up and turned them into something else. Marc Happel, who runs the costume department, helped me out.

Is costuming something that interests you?

It’s something that I think I need to be very conscious of because I’ve seen so many ballets be ruined by costumes. It’s crazy how much garments can alter or muffle the choreography. It’s hard to find designers who design well for dance. I haven’t found a designer yet who has really caught my eye. I looked around a lot to find someone less known for this ballet [Year of the Rabbit, which premières on Oct. 5], but it was hard to find someone. So I’m working with Marc Happel on the costumes. I’ve given him extensive notes and parameters. It’s probably terrible for him to have to deal with.

It sounds like you’re very detailed. Where do your ideas come from?

I wrote essays of information and references for Marc regarding what I want for the costumes, and we’ve gone through several phases of design. I made a lot of references to other ballets. I want to find a midpoint between costume and practice clothes. Color is a big issue. I gave Marc several options for color palette. I want the costumes to come in two to four colors, because I don’t want it to be too overwhelming. And I want the principals to have the same sort of color palette as the rest of the cast, only slightly lighter or slightly darker, because I want them to be able to be incorporated in the cast but also be featured when they need to be. This ballet is going to have a big sense of community in it.

What about lighting?

That’s something I’ve been working on very extensively. I’ve brought on a really young lighting designer, Brandon Stirling Baker. The ballet has seven movements, and we want to distinguish between the movements through the lighting as well as the choreography. He’s very hard-working and passionate, and he’s young and I think he’ll have some new ideas. I don’t want the lighting to distract, and I don’t want it to be too dark. That concept has been so exhausted. There are going to be different levels of brightness and we’re going to work with color a bit. In Creases was more sleek and modern in its design. The music too.

What is the music for In Creases?

It’s by Philip Glass, something he composed in 2008 [Four Movement for Two Pianos], a really great piece for two pianos. I was skeptical about using his music at first, because everyone has used it. But ultimately it came down to the fact that it’s very good danceable music, and also – perhaps because it’s newer and maybe Glass is at a different point in his career as a composer – it seemed to me that it’s a little bit more expansive than usual. There’s more to it, and it has sort of a romantic quality. Also, I wanted to challenge myself, because before then I had mostly worked with composers who have a more complex way of writing, so this left me feeling more exposed. It felt closer to blank canvas. All of a sudden I had more options about what I could do. It felt like there were passages that I could sculpt in any way; the music gives you parameters and then you can do whatever you want within that. You can take a phrase that’s repeated four times and do four different things, or ABAB, or ABBA….

Are you also influenced by popular culture?

A little bit…well, I don’t know how much that translates into my work. A bit. But I’m interested in new music, and collaborating with living composers. There’s been a bit of that working with Sufjan Stevens and Michael Atkinson on Year of the Rabbit. Atkinson helped arrange the music for orchestra.

What is the music for Year of the Rabbit like?

It’s definitely melodic. The original was for string quartet, which has been expanded for string orchestra. We talked a lot about how we wanted to orchestrate it, and we ultimately decided to distill it down to just strings. We were a little worried about what it would turn into if we did full orchestra.

Too symphonic?

Maybe, yeah, but I think it works so well with just strings. And it has percussive elements as well, and incorporates inventive ways of using the string instrument. Mike [Atkinson] is going to conduct it. He has played in Sufjan’s touring band, and he went to Juilliard. He plays in a chamber orchestra called The Knights, based in Brooklyn. And he conducted Sufjan’s BQE, an orchestral suite he composed which premiered at BAM in 2007.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

How did you come upon Sufjan Stevens’ music?

I go to a lot of concerts and listen to a lot of music. I’ve been a fan of his for a while, and then I heard this interview on WNYC with the string quartet that recorded the music. They played a few of the movements, and the music immediately caught my attention. I archived it as a piece I wanted to choreograph to.

What drew you to it?

Sufjan has an innate ability to write danceable music, which is weird, because he has no background in dance. His music has a pulse, it has melody, it’s inventive, and he’s able to draw from composers of the past while still maintaining his own voice, which is really rare.

Is that rhythmic quality important to you?

Yes. And the time signatures are interesting. He uses a lot of 7/8 and nine counts and five counts. But still, the music has very strong structure and lots of little details and subtle nuances. The thematic aspect is also interesting; it’s very loosely based on the Chinese Zodiac, but only from his experience of reading Chinese menus in midwestern restaurants growing up. I mean, if you really start researching the Chinese Zodiac, it’s a very deep rabbit hole.

How about the ballet?

I started reading about the zodiac a bit, and then ultimately found that it would drive me crazy if I tried to do something entirely based on that. But if I ever got stuck, I would read passages, and certain words would stand out. I remember reading “linear in the year of the ox,” and that line sparked a particular structural arrangement with the corps. What I think is interesting about the zodiac is how each animal sign relates to other animal signs, so I tried to take certain fragments of movement and incorporate them into two separate zodiac signs that relate to one other, but in a really subtle, modified way. So it’s not so noticeable if you watch it once, but maybe after a couple of viewings you might pick up on little relationships.

Are you interested in telling stories?

It’s definitely something I want to explore. I think I’m probably not ready yet.

It sounds like you’re more interested in structure.

For now at least…. I want to find a really good story to tell through dance. I had this idea – I just read IQ84 [by Haruki Murakami], and the way it’s written is really interesting, in that it’s two separate storylines told in alternating chapters. Eventually the two protagonists meet at the end. So it would be interesting to do something like that with a ballet.

You’ve danced quite a few ballets where you play a character, as in Liebeslieder Walzer. There’s not a single story, but many stories.

I’d probably be more inclined to do something like that. If I had to choose one thing to dance, it would be Liebeslieder. It’s such a subtle work. You get more and more out of it with each viewing. Maybe because of the set and the fact that the musicians and singers are onstage, it’s very intimate. It feels like no-one is really watching. There’s definitely this communal feel.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

It sounds like you’re describing a Robbins ballet.

But this is much more subtle. It takes more digging to figure out than a Robbins ballet. It’s very specific.

There are volumes of story in each pas de deux.

Absolutely.

You’ve danced a lot of Robbins at City Ballet. For example, that section of Glass Pieces where you lead the male ensemble.

I love doing that. It’s one of my favorite things to dance. Usually the corps supports the principals, but in Glass Pieces it’s the principals who support the corps. The corps is the real heart of that work. It’s something I want to incorporate into Year of the Rabbit. I want to create a sense of equality between the corps and the principal dancers. I’m interested in breaking up that fragmented way of presenting dance. I want to create a more seamless environment. And I want to play with transitions a lot. The piece lends itself well to that, because there are seven movements.

How many dancers will there be?

Eighteen, with a corps of twelve. But there will be moments where dancers in the corps will become soloists. If you compare it with the ballet I just did [In Creases], this one is much more human. That one was mechanical and sleek, and cold in a way. This one’s going to be much warmer, both the choreography and the costumes and lighting.

Are you also interested in moving the art of the pas de deux in a new direction?

I’m interested in exploring an equal relationship between the man and the woman, and not so much in the man displaying the woman. I want to get away from that a little bit. I’m more interested in creating a more fluid relationship between the two dancers, and a more effortless look.

Are you committed to the pointe shoe?

I thought about maybe taking away the pointe shoe for parts of this ballet, but it’s a tradition I want to hold onto. On a simplistic level, it’s really beautiful. Being on pointe is very esthetically pleasing [here, Peck’s voice grows slightly dreamy]. And then, the pointe shoe allows a lot of flexibility in how it works in relation to the floor. There’s a lot to be explored with that. And it’s fascinating to me, because I don’t know how it works, since I don’t dance on pointe. I’m trying to explore what it may be able to do.

Do you think there are still possibilities to be discovered?

Yeah, or certain combinations of footwork that might prove to be interesting. I don’t know, I’m just getting started [laughs shyly].

You’re dating one of the loveliest and strongest dancers in the company, Teresa Reichlen. Does she influence your ideas about choreographing for women?

I think that maybe she helps in that she’s so capable and gifted, so she’s a good person to test things out on. Because she can do anything, so why not have her try things…

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Is she in Year of the Rabbit?

She is. Actually, it’s a struggle to find her a partner, because she’s so tall and her limbs are so boundless.

You’ve partnered her in the past.

Yeah, but actually, even for me it’s hard, because I’m almost a little too short for her. I choreographed a pas de deux for the Youth America Grand Prix gala a few months ago, and it was supposed to be Tess with a dancer from the Dutch National Ballet, very tall, very long limbed. But he wasn’t musical, so I had a hard time. Maybe I’m spoiled because I’ve worked mostly with City Ballet dancers, who are tremendously musical. Anyway, he ended up getting injured, so at the last minute I had Robbie Fairchild perform it. He’s very musical and they worked really well together. So I’m going to pair them up in this ballet. He also had a standout role in In Creases. I’ve known him a really long time, since we were room-mates at SAB when I was 15, so I have a firm grasp on his movement and his idiosyncrasies and everything about him. I know him on a very personal level. The other couple is Craig Hall and Janie Taylor. [There are two principal couples in Year of the Rabbit.] I’m planning to use the two couples in very different ways.

How do you go about finding music?

I used to study at Columbia, through the GS [General Studies] program. I’ve sort of stopped that for now because things have gotten too crazy. It’s such a slow process, you can only take one or two courses at a time. I started by going to the music library, and I would check out a stack of cd’s every week. I would go through a specific composer’s catalogue, and whatever spoke to me I would check out. It’s hard, because music is such a vast pool. I actually have an archive where I keep music I want to choreograph to.

What draws you to this or that piece?

It’s hard to say. It’s sort of an intangible thing. I wouldn’t stay there’s a stand-out period that I’m drawn to. But it’s not just a matter of finding the right music but also music that hasn’t been choreographed to before. I do a lot of research on the internet, a lot of listening on Spotify…

Other than Ratmansky, which choreographers working today do you admire? How about someone like William Forsythe?

We got to meet him as part of the Institute program, when his company was here at BAM [to perform I Don’t Believe in Outer Space, in 2011]. He was really inspiring to talk to. I think he’s really innovative. It’s funny because so many people copy his style, but somehow when you see his work it stands out.

He uses a lot of text in his work. Does that sort of thing interest you?

Maybe. One day. It’s hard to do something like that unless you have a lot of time. I think it works for him because he has his own group, and he can spend 8 months working on a piece. He was telling us about how he feels this loyalty to his dancers, and how he wouldn’t want to come and choreograph for anyone else. Everyone’s very dedicated, so they’re able to make something great no matter how long it takes. I admire that. I’d be curious to go and see how he works in the studio and in rehearsals. A lot of his movement is very conceptual. Have you ever seen those movement videos he made [Improvisation Technologies]? It’s like, you have to figure out how you would move if there were a rod here, and how would you move around it, that sort of thing.

I always think those sorts of things sound more interesting to do than they are to watch, in a way.

Yeah. I agree.

Do you think dancers find it interesting because it engages their brains, not just their bodies?

There are other ways to stimulate dancers’ minds, though. This is something I might have picked up from Ratmansky too, but I use imagery or metaphor to draw things out of dancers, or even groups of dancers.

© Justin Peck. (Click image for larger version)

Engaging their imagination?

Yeah. I think it helps to create a real depth in the way the ballet is being performed, if you do that.

Have you had a mentor along the way?

No, it’s very lonely out there. [laughs] There’s no structure for it, and the really great choreographers are too busy to worry about that sort of thing, or maybe they’re not interested. At the Choreographic Institute it’s very sink or swim. What you get is space and time and resources. At first I was a little frustrated, but I understand how they don’t want to influence choreographers too much. I mean, it would be nice to have some sort of mentorship with regard to what it takes to be a choreographer. I think there are a lot of gray zones, especially with practical things, like working on commission. Every once in a while we get the chance to ask someone a few questions. But for the most part everyone’s kind of on their own.

No late night sessions with Christopher Wheeldon to pick his brain?

No. I wish. (laughs) I mean, he’s hardly in New York; he’s always working somewhere.

Would you be interested in a program where they gave you assignments: ‘now make an opera ballet, and now, make a pas de deux,’ that sort of thing…

No, that would be good. I don’t think that exists anywhere though. That would be amazing. I was talking to my friend who’s studying at Juilliard as a composer, and they have a mentorship program, so they meet with Christopher Rouse, or John Corigliano. But I feel like what ends up happening is that there is an expected way that they all have to compose, or a style. If you want to compose in a different way, it means you’re not a serious composer. I think it causes a lot of the music to sound the same. So in a way it can be healthy not to have that. Neither option is ideal.

When you were at SAB, you’ve said that you watched a lot of City Ballet. Did you see American Ballet Theatre as well?

Yeah, I saw them too, but it didn’t have the same effect on me as City Ballet, especially Balanchine. It was about the musicality, especially in the Stravinsky works, but also something about what I was seeing at City Ballet felt very important. It was the first time I had seen a devoted audience for an artform. There’s nothing like that in California.

Does that level of devotion ever feel a bit claustrophobic to you?

No, I love it. I think that it’s great that people know what they want.

What do you think of efforts to “dumb down” ballet or make it more accessible to a wider audience?

No, I don’t think that’s a good direction to go in. I think sacrificing the quality is not the right direction.

Have you been getting a lot of inquiries?

A bit. I’m interested in working elsewhere, for sure, but my first priority is creating for New York City Ballet. I’ve been thinking a lot about how choreographers work, and it seems like now there’s a movement toward going everywhere and globalizing the creative process, but if you think back to the way Balanchine and Robbins worked, they were very devoted to creating for this institution, and I think because of that their work was very focused. I think they were able to create some of their best work because of that. That’s not to say I don’t want to work anywhere else. I think it would be interesting to go work in other places to see the difference in the training and the style; it might be a good growing experience.

Have you had a lot of support from within the company?

Yeah, Peter Martins has been really great about giving me creative freedom, and if I have ideas I can come to him. I think he has a lot of faith in my work.

Has he expressed that openly?

He has, a few times. It’s a big step, for me and for him. Because he doesn’t really like to influence the process or the outcome of a choreographer. So those few moments where he does express his approval or his interest are very meaningful. But for a long time the only way I could tell he was interested in my work was because I would continue to get offers to work or commissions.

How did the first commission come about?

I choreographed a short pas de deux for the Columbia Ballet Collaborative, and it got reviewed in the Times, two sentences or something in a review. Peter Martins read the review and called me and asked to see the piece. So then he watched it and asked me to do a session at the Choreographic Institute, and then another session, and then they created a position, a residency for me to work at the institute this past year.

How does the residency work?

It provides a level of consistency, so I was able to work on three pieces over the course of the year. And they give me a stipend if I need any financial support. I can use it however I want, but if I need financial help in order to fund some sort of project, I can draw from that. So I’ve used it a little bit for these short film projects I’ve done. I’ve made three short dance films – one is going to come out in a few weeks. Those were in association with fashion magazines, for the fashion house Chloe.

Janie Taylor and Justin Peck dancing in advertising feature…

NOWNESS.com presents: Janie Taylor for Chloe

New York City Ballet principal Janie Taylor road tests Chloé’s dance-inspired spring/summer 2011 collection with choreographer and corps de ballet member Justin Peck in this short by director Bon Duke.

I’m working on another film now. I was just out on Long Island scoping out a location. We’re trying to promote the ballet in a different way, and Ellen Bar [a former dancer at NYCB who co-produced a film adaptation of Jerome Robbins’ NY Export: Opus Jazz] and I have been talking about doing a conceptual movie trailer to promote the ballet, which is coming out in October. We’re going to release it on a site called nowness.com, and it will be released onto the web. And it’ll probably be on the City Ballet YouTube page. We’re going to shoot it at Jerome Robbins’ beach house on Long Island. It has this really modest look to it, like an old fisherman’s shack. It’s small and private and has a lot of character and it’s right on the beach. We’re making this really brief film there and bringing out a young film-maker to work on it. Janie Taylor and Craig Hall are going to dance in it. The film-maker’s name is David Yoonha Park. We’re having the cinematographer from NY Export work on it as well.

Year of the Rabbit Promo

Set to “The Palm Sunday Tornado Hits Crystal Lake” from The Avalanche. Directed by Yoonha Park and features dancers Janie Taylor and Craig Hall.

Choreography, in a way, is such an act of courage and self-confidence. Where does that come from?

I think I’ve been wanting to do this for a while, it’s always been something in the back of my mind. And I feel like I have a lot to share. I thought about maybe just focusing on dancing, but I feel too restless, like I want to start working on this. What I love about dancing is performance, that moment onstage, because there’s no attention paid to the past or the future, it’s all in that moment. I think that’s a hard thing to achieve in any other way. It’s like an addiction. But the process of choreographing is in a league above for me.

So how far along are you on Year of the Rabbit?

Well I haven’t really started yet (laughs). I was supposed to begin in the spring, and then In Creases came about at the last minute, so the time was occupied by working on that. Once In Creases premiered, I started on this ballet but I only had one dancer, for three days. I have just under six weeks to make it. And it’s a pretty substantial piece, about 28 minutes long. I have a lot of notes (laughs).

Does it feel like a lot of pressure?

No. I’m really eager to do this. I feel like I have a really strong vision for this work, and I’m just waiting to express it. It’s like at the races, when the horses are waiting for the gates to rise. I’m ready to sprint.

[…] I spoke with Justin in August, before he began working with the company on “In the Year of the Rabbit,” which will première on Oct. 5. Here is a link to the interview. […]

Perfect….