© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

ABT’s Fall Season: A Short and Snappy Season

American Ballet Theatre

Drink to me Only With Thine Eyes, Cruel World pas de deux, pas de deux from Stars and Stripes, Rodeo, The Moor’s Pavane, In the Upper Room

New York, City Center

16-17 October 2012

www.abt.org

www.nycitycenter.org

American Ballet Theatre is back at New York City Center, if only for the blink of an eye. But what the season lacks in length, it makes up for in repertory, though, it must be said, none of the works really fits the category of “contemporary”, at least not in the way the term is usually understood. I.e. there is nothing particularly edgy in the ballets on view – no complicated distortions of technique or multi-media spectacles. That is unless Alexei Ratmansky’s new Shostakovich piece, Symphony No. 9, (premièring on Oct. 18) turns out to be a radical departure. Ratmansky may be writing the next chapter in ballet, but he’s not really trying to move it in some drastic new direction. He works from within, tweaking and re-framing its classical forms, reinventing them with his playfully sophisticated eye.

But I digress. This season, in addition to the new Ratmansky piece, the company is performing five full works, plus one bravura excerpt (the pas de deux from Balanchine’s Stars and Stripes) and one gala fragment, a swoony, lift-filled duet from James Kudelka’s Cruel World. Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo has been brought back, just in time for its seventieth anniversary. At the gala (Oct. 16), Frederic Franklin, the original Champion Roper – the ballet’s winsome, tap-dancing hero – was in attendance, sparkly-eyed and beaming at ninety-eight. Another work being revived is The Moor’s Pavane (1949), José Limón’s elegant modern-dance quartet on themes from Othello, which hasn’t been danced by the company for over thirty years. Later in the week we get Antony Tudor’s melancholy ode, The Leaves are Fading, from 1975. And on into the eighties: Twyla Tharp’s Philip Glass-fueled tour de force In the Upper Room (1986) and Mark Morris’s Drink to Me Only With Thine Eyes (1988). (Baryshnikov’s influence on the company is still strong; he commissioned the Morris and acquired the Tharp during his tenure as artistic director.)

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

The gala program was on the short side, the better to leave time for the all-important post-performance shindig for donors and VIP’s. There were the usual speeches and poufy dresses, studiously curled coiffures and boulder-sized bling. Even so, the whole affair had a less frenzied, glam feel than its New York City Ballet counterpart a few weeks back. I spotted Mr. and Mrs. Ratmansky during the only intermission, quietly conversing in their seats in the empty hall, an island of quietude away from the crush. The evening began with Drink to Me Only With Thine Eyes. Like Morris’s Canonic ¾ Studies, it’s an affectionate spoof on ballet. The music is Virgil Thomson’s Etudes for Piano, convincingly played by Barbara Bilach (in the pit). Despite some (intentionally) dissonant passages, the pieces are not so different from the music one might hear in a ballet class: a waltz, a tango, a gentle rag. Each roughly corresponds to a certain kind of movement – sharp, legato, staccato, turns, jumps! The dancers go through their paces, almost as if completing exercises, though these exercises look rather more fun and more off-kilter than the kind one gets to do in class.

Drink begins with a succession of solos, as dancers rush on, launching into big jumps with the knees tucked under and the arms held up, crossed at the wrist. Plop, plop, plop they go, one after the other, wearing loose, stretchy, cream-colored costumes by Santo Loquasto, a prettified version of 1980’s dance-wear. (The women wear leggings and skirts and tops with ample sleeves and open necks, the men loose, comfortable-looking jersey trousers and long-sleeved tops. The arabesques are low, and so are the lifts, which tend to be brief (except when the men carry the women over their shoulders like sacks of potatoes). Rows form and dissolve; the dancers regroup into shifting patterns – two versus one, six versus six, one versus two versus three, etc. Motifs emerge, like a funny promenade in which the men awkwardly support the women, tilted at an impossible angle so that the men bear all the weight. There is no way to accomplish this elegantly, so instead it’s rather funny. But there are lovely, lyrical moments as well: a section in which two women simply glide in from the wings and back out again, a waltz filled with big juicy balancés, using the whole back, with an extra swish of the arms at the end. Each of the twelve dancers has his or her moment; it all seems quite egalitarian, until it isn’t.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

As the chords of an emphatic tango ring out, Herman Cornejo launches into a series of perfectly controlled pirouettes, stops with his leg held up to the side, swishes it around a few times, tilts over, jumps to the side, and starts over, except that now he’s turning on a bent leg, in attitude, and lowering himself to the floor. Later, he flips through a whole catalog of jumps, ticking them off like a checklist. The delivery is exaggeratedly academic, even grandiose: see, this is how it’s done. The solo was originally created for Baryshnikov, but now it belongs, with all due respect, to Cornejo. (On Oct. 17, it was danced by Joseph Gorak, beautifully, with exquisite control and high extensions, but without Herman’s panache.) All in all, though, both of the performances I saw (Oct. 16 and 17) were a little stiff; the ballet should look academic, but also lyrical and lighthearted. At this point, it’s somewhere in between. In addition to Cornejo and Gorak, there were several standouts. On Oct. 17, in the second cast, Stephanie Williams, who joined earlier this year, seemed to glide through the steps as if she had wandered in from a dream. Thomas Forster (also on the 17th) painted the air with his long, pliant frame, swishing his arms with a slightly mischievous air.

More generally, I was struck by the lushness of the dancers’ movements, and by the generous way they use their backs. Again, it’s built into Morris’s choreography, but it’s also part of company style, and I’ll admit it’s a welcome change from the frontal look one sometimes sees at New York City Ballet. It really comes down to épaulement – the twist in the upper body and shoulders that make a dancer look like a three-dimensional figure in motion and not simply a body with a front and a back. Simply put, it’s what makes dancers look interesting. It’s natural for some of this twist to be sacrificed for speed and lightness – and the City Ballet dancers are wonderfully fast and light. But without it the steps look superficial, disconnected. You don’t feel them in your bones. Of course this is not true of everyone at City Ballet; all the most interesting dancers, like Tiler Peck, Robert Fairchild, Tyler Angle, Sara Mearns, and others, really bend into the movement, but it doesn’t seem to be standard policy.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

On the other hand no-one dances Balanchine’s Stars and Stripes like the home team. ABT’s première of the cheeky pas de deux was given to Sarah Lane and Daniil Simkin as a party showpiece, perhaps because the young wiz-kid Simkin needed something to show off his big jumps and perfectly-placed turns. No doubt about it, Simkin can give a good show, eliciting gasps with each airy leap (including some interpolated “540” jump-flips), but my enthusiasm was dampened by the lack of chemistry between the two dancers. Lane looked frazzled; Simkin’s partnering was rough. The soufflé deflated. Added to which, neither dancer really captured the wit and charm embedded in Balanchine’s scintillating footwork. That’s where all the fun lies. On the other hand at least Stars and Stripes has actual footwork, unlike the pas de deux from James Kudelka’s Cruel World, performed by Julie Kent and Marcelo Gomes (another gala morsel). To Tchaikovsky’s sumptuous Souvenir de Florence, Kent looked vulnerable and forlorn as Gomes lifted her, often above his head, in various sculptural poses. Kent may be light as a feather, but still, it seemed Gomes got the short end of the stick.

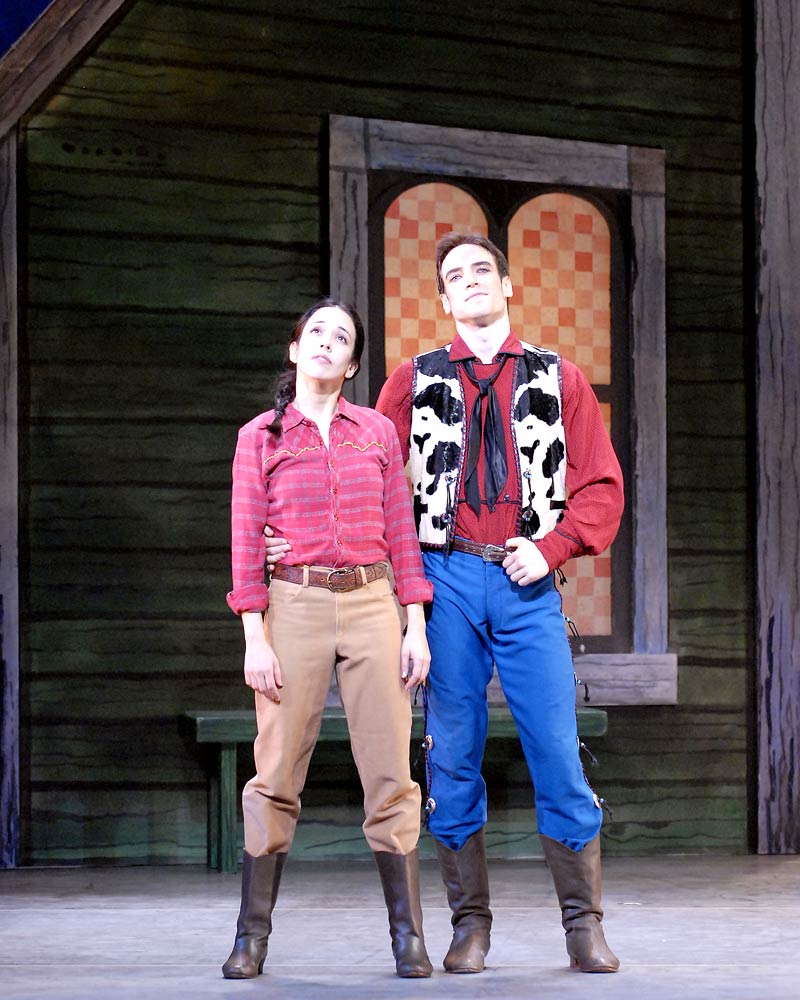

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

The highlight of the gala was the seventieth-anniversary performance of Agnes De Mille’s Rodeo, preceded by a short film describing its creation, with archival footage of the hilariously histrionic, diminutive choreographer. Xiomara danced the role of the Cowgirl with great pluck and simplicity; it helps that she looks like she’s about sixteen, with big, saucer-like eyes and a tomboyish build. The rest of the cast members hadn’t quite gotten De Mille’s down-home style into their bodies, with the exception of Sascha Radetsky, who dances the role of the Champion Roper with all the awe-shucks charm you could ever want. ABT’s men haven’t mastered the art of the cowboy walk or the bow-legged, relaxed stance; maybe the ballet has been out of the repertory too long. But it worked anyway. Like Jerome Robbins’ Fancy Free, Rodeo is so simple and so well-constructed, and Copland’s music is so glorious, it simply can’t fail.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

On the second night, after presenting another cast of Drink to Me Only With Thine Eyes, the company danced The Moor’s Pavane, coached by the Limón veteran, Clay Taliaferro. Gomes was the Moor, with Cory Stearns as his treacherous deputy, Iago, Veronika Part as Emilia (Iago’s wife), and Julie Kent as Desdemona. The quartet is formal and grave, filled with exaggerated courtly dances and stylized poses that reveal Iago’s deceit, Emilia’s wheedling, Desdemona’s fatal passivity. Limon’s Moor is stolid and proud, with a penchant for violence – he stomps on his friend when he doesn’t like what he hears – that belies a profound weakness. Gomes attacked the character with his characteristic zeal, infusing each deep plié with seething emotion. Stearns was convincingly creepy and pleasantly understated, lunging and pawing at his sovereign. Kent had little to do but look devoted and ripe for the kill. But Veronika Part stole the show; it became the story of her desire to regain her husband’s attentions by aiding him in his plot to destroy Othello. In her hands Desdemona’s handkerchief became both an erotic toy and a weapon. As usual Part’s power lies in her strong, pliable back; she can initiate a movement from the very base of her spine, so that you feel its weight in your own body. Despite Pavane’s somewhat blatant themes, it has impact, and it suits these dancers.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

The season’s second evening closed with the onslaught that is Twyla Tharp’s In the Upper Room. Boxing, cheerleading, aerobics, karate, ballet, it has it all, in addition to what is probably Philip Glass’s most sumptuous music. The dancers appear and disappear into the smoke, exuding a kind of all-American cool, rolling their heads, swinging their arms, shaking their shoulders, swiveling their hips. Isabella Boylston was an impossibly sleek, sexy lead ballet girl, in her red pointe shoes and socks, her red leotard peeking out from under a black-and-white striped skirt. And again, there was Herman Cornejo, quietly intense as he sailed through the air or executed beautiful, clean pirouettes, or simply went with the flow. The whole ballet is irresistible, a never-ending crescendo leading up to an apotheosis on steroids. Like Rodeo, it works every time.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

You must be logged in to post a comment.