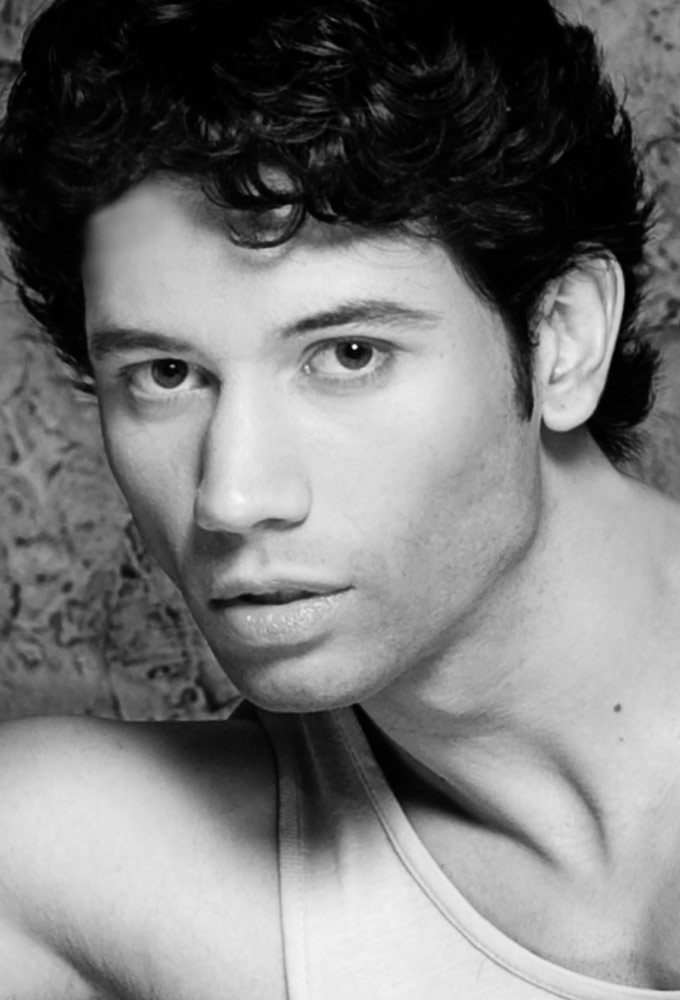

© Manuel de Los Galanes. (Click image for larger version)

A Prince Who Leads With his Heart

www.hermancornejo.com

www.abt.org

American Ballet Theatre’s Herman Cornejo has had a remarkable year. Since coming back from an injury, he has danced Solor in La Bayadère (with Alina Cojocaru), Pyotr in Alexei Ratmansky’s The Bright Stream and Ivan in his new Firebird, and more recently, in the fall, an explosive role in Ratmansky’s new Shostakovich ballet, Symphony No. 9. During the company’s Metropolitan Opera House season, he stole the show in Frederick Ashton’s The Dream, sculpting improbable shapes in the air and imbuing the role of Puck with an exotic, almost otherworldly, quality that made it both exciting and a just a little creepy. In addition to his usual musical responsiveness and finesse, his dancing seems to have acquired a new expansiveness, a kind of easy panache that never goes so far as to seem showy.

Cornejo has been a principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre since 2003. After training in Argentina at the school of the Teatro Colón, he won the gold medal at the International Dance Competition in Moscow at the tender age of sixteen. By then he was performing leading roles with Julio Bocca’s Ballet Argentino. Bocca has been an important mentor: he encouraged the young dancer to come to ABT, where he was already an established star. Cornejo’s sister, Erica, joined the company at the same time; many can remember the siblings’ joyful complicity when they performed the gypsy dances in Le Corsaire as Birbanto and his saucy lass. Now Erica is a principal at the Boston Ballet. Cornejo, whose small stature – he is five foot six – has probably been his greatest handicap, is finally getting the roles he always burned to dance: Romeo, Solor, Prince Désiré, the Nutcracker Prince. In Ratmansky he has found a choreographer attuned to his particular gifts and determined to push him even further. On a recent evening, we sat down to chat at a café near the company’s studios just north of Union Square.

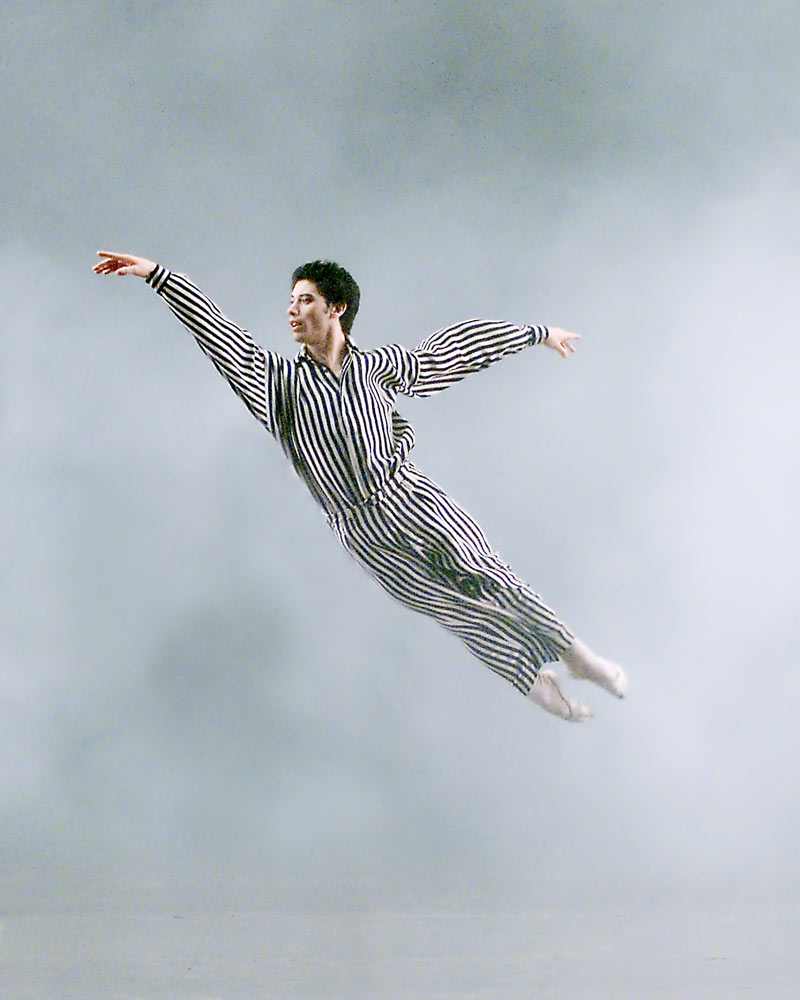

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

You had quite a fall season. Alexei Ratmansky created such a striking role for you in his new ballet, Symphony No. 9. You’re sort of the force that binds the whole ballet together.

You know, it’s amazing, because he created it so quickly. We didn’t have much time to work on it. He made the role in a week. I would be sitting in a rehearsal, doing nothing while he worked with the other dancers, and then in the last ten minutes he would work with me. Until the very end he only had a few minutes of choreography for me, and then in two days, he basically created the role.

That’s surprising, because the role is so central to the ballet. Do you think he had planned it all ahead?

I don’t think so, because you know originally I was supposed to have a partner, but then she was injured, and I guess he decided for some reason that I should dance alone. So I don’t think he knew at first what the role would be.

Did you talk about what the role meant? You’re like an angel or a spirit, almost a vision, in the second movement.

He said he saw me as a kind of guide or protector for the main couple.

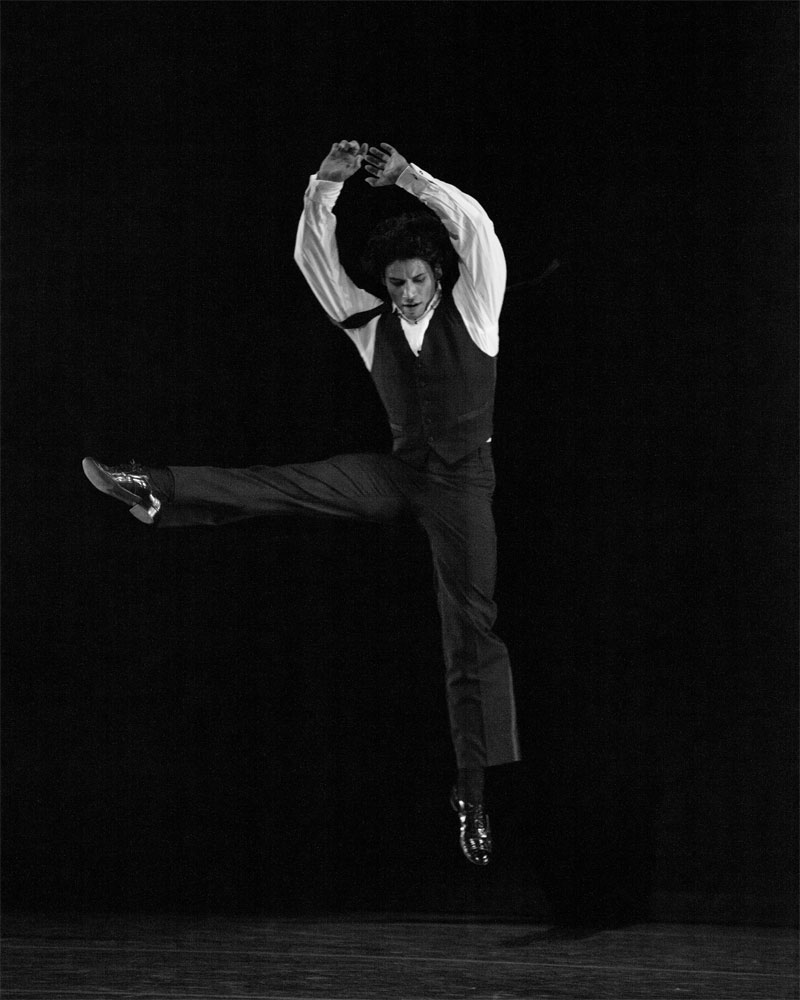

© Manuel de Los Galanes. (Click image for larger version)

When did you realize what a strong impact it would make?

I think it wasn’t until after the first performance.

What’s it like working with Ratmansky in the studio?

He’s very detailed, very specific; he wants things to look a certain way, with a lot of turnout and a certain shape, but at the same time he allows you to find your own way of interpreting the role, your own shadings, to make it reflect something about you. Ratmansky’s ballets are very difficult to dance. They’re very demanding, physically, but also dramatically, because he asks you to express the story in the movement, not in moments of mime followed by classical dancing, but through the movement itself, the quality of the movement. But it makes such a difference to have him in the studio, creating things with you. As a classical dancer I always wanted to dance the classical roles, but to have him here to work with over and over, to know that there will be a next time, and a time after that, that’s really something very special.

Also, you know, there has been a lot of turnover in the corps in recent years, and suddenly there were all these new corps members, and it was almost like the company’s ability to create all the intricate details of a story ballet had eroded a little bit, and Ratmansky is building that up again, bringing it back.

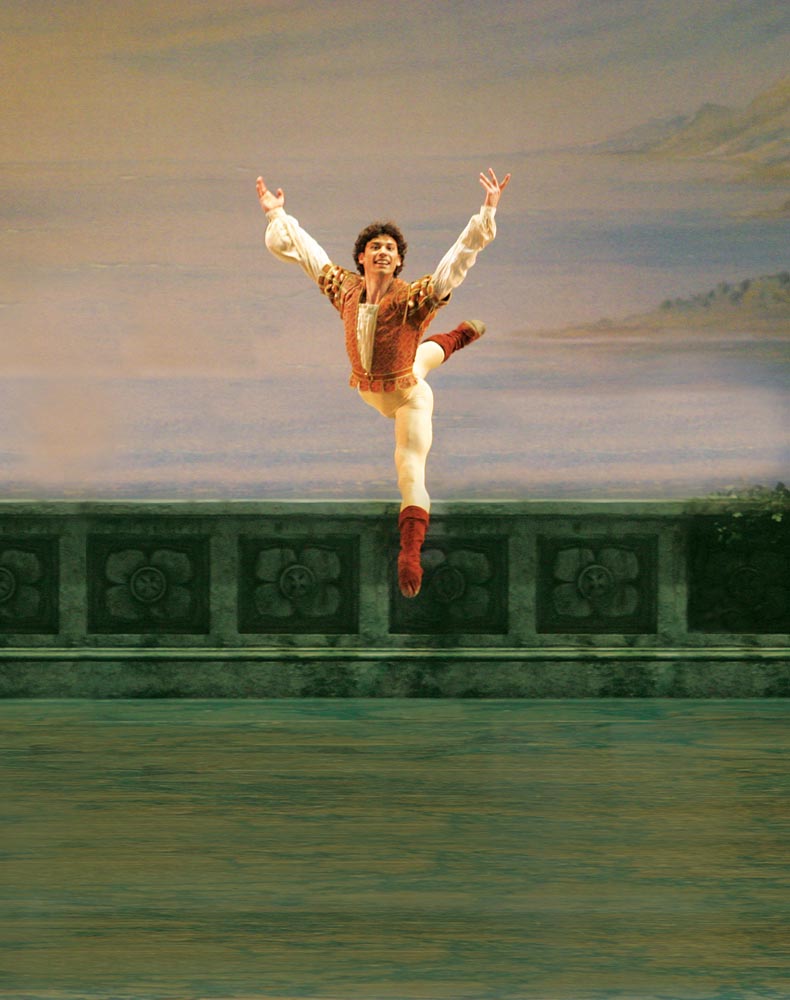

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

You were injured toward the end of the fall season. How is your recovery progressing?

I tore a calf muscle. Unfortunately it means I won’t get to dance during the Nutcracker season. I just have to let it heal. Next week, I’ll start taking class.

Despite the setback of the injury, you’ve had quite a year; you danced your first Bayadère for ABT (with Alina Cojocaru), and you danced Ivan in Ratmansky’s Firebird, and Puck in The Dream. You’ve gotten to dance pretty much all of the big roles in the story ballets at this point. What has that been like?

Well you know, it took a long time for Kevin [McKenzie, artistic director of ABT] to give me the principal roles in the classical ballets, even when I was already a principal. And yes, sometimes it was frustrating, but you know, now that I think about it, I feel like things happen when they are supposed to happen. I’m ready, I feel different about them now. Also, coming back to the Met after having been injured for almost four months I felt very different. Maybe it was because I was so happy to be back there, but I had rested, I’d had time to think about things.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

What was it like creating the role of Ivan in Ratmansky’s new Firebird? Each of the Ivans [Marcelo Gomes and Aléxandre Hammoudi were the other two] was quite distinct. Yours had a kind of innocence and ardor.

Well, we talked about it, and I see Ivan as a kind of warrior. To me, Ivan is a warrior on a quest to save this maiden, this princess, his love. Despite all the fantasy of Ratmansky’s production, the colorful costumes, I wanted it to feel real, true. I enjoy playing warrior characters, like Solor. Solor is my favorite role, actually. I love the groundedness and the nobility of those roles. He’s a prince, but not one who leads with words, but with action, with movement. You have to show your heart, your soul.

In a completely different vein, you’ve pretty much come to define the role of Puck in The Dream.

With Puck this time I wanted to do it a little bit differently from how I had done it before. On the dvd I made him light, playful, but now I wanted to make him a little bit more frightening, more creepy. I love that; every performance is different. But this time, maybe it was a little bit harder, because I almost felt like I had to live up to a DVD that was made ten years ago. You’re always competing against yourself.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

Do you feel the pressure of time?

I think every dancer feels that, especially male dancers. You know, technique is always evolving, always moving forward, and there are always new, younger dancers.

Do you think there’s too much emphasis on tricks in ballet?

In a way, yes, but it’s always been there, it’s part of the art. Of course, sometimes I think: I go out and try to dance as beautifully as I can, and then I see someone else going out and doing tricks, 540’s and things, and people clap just as much, and you wonder, maybe it’s all the same to them? But then, that’s normal too, different people want different things. I don’t feel like I have to compete with other dancers; I only compete with myself. I always want everything to be beautiful, and to express something. That’s what matters to me.

Ballet is a cruel profession.

Yes, I always say: you love it, but it doesn’t love you back. When you retire there’s always someone right behind you.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

You have such a modest quality when you’re on stage; it’s especially noticeable when you’re in an ensemble work like Mark Morris’s Drink to Me Only With Thine Eyes or Twyla Tharp’s In the Upper Room.

Well, performing for me is really about that experience of giving to the audience. In the studio you work and perfect things, you collaborate with your partner, but for me it’s about what happens on the stage, the ability to give something, to your partner, to the audience. In the studio and the rest of the time I’m just like anyone; the only time I feel different is on stage. It’s interesting, too, because, you know, we were talking about Ratmansky before, and both he and Mark Morris are so musical, but their musicality is so different. Morris’s choreography wraps itself into the music, but with Ratmansky, it’s almost like the movement creates the music, almost like he wants you be even slightly ahead of the music, so the movement and the music are actually one.

Like that moment in Ratmansky’s Seven Sonatas, when you come in for your solo, and even before the note rings out on the piano, you appear in midair?

Yes, even before the music starts.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

How about a ballet like Twyla Tharp’s Sinatra Suite, which was originally conceived for Baryshnikov? Your interpretation is so different from his.

Yes. I talked to Nancy Raffa [ballet mistress at ABT] and Twyla about it, and I told them that in order for it to work for me I had to make it my own, I had to express something about myself. With Baryshnikov, the ballet was really about him, but to me, it’s about the man and the woman, the relationship between them. For the past two years I’ve danced it with Luciana Paris. We’ve known each other since we were seven in Argentina, we practically grew up together, and we’re really good friends. In a way, it makes it harder in the first pas de deux [Strangers in the Night], because we have to create that tension and excitement of two people who have never seen each other before. It’s about the two of us. That last pas de deux with Luciana [My Way], for me, it’s about having to part with someone you love, even though the passion is still there, and that’s something I can understand. When I do that final solo I have a lot of memories, not precise images, but moments and sensations of things I’ve experienced. It leaves me feeling very empty.

You travel so much; is it hard to stay close with your family, your parents in Argentina and your sister, who’s a principal at the Boston Ballet?

We don’t see each other that much, but we’re very close. For the past couple of years my mother hasn’t been able to get a Visa to come see me dance in the US. Sometimes she comes to see me dance in Europe. But it’s sad that she can’t come to the place where I live and my sister lives, and see us perform here.

Was the distance hard on your marriage, to Carmen Corella?

Yes, it was hard, because we couldn’t be together, we couldn’t make it work. When we separated, we had been talking about adopting a child. I do want a family.

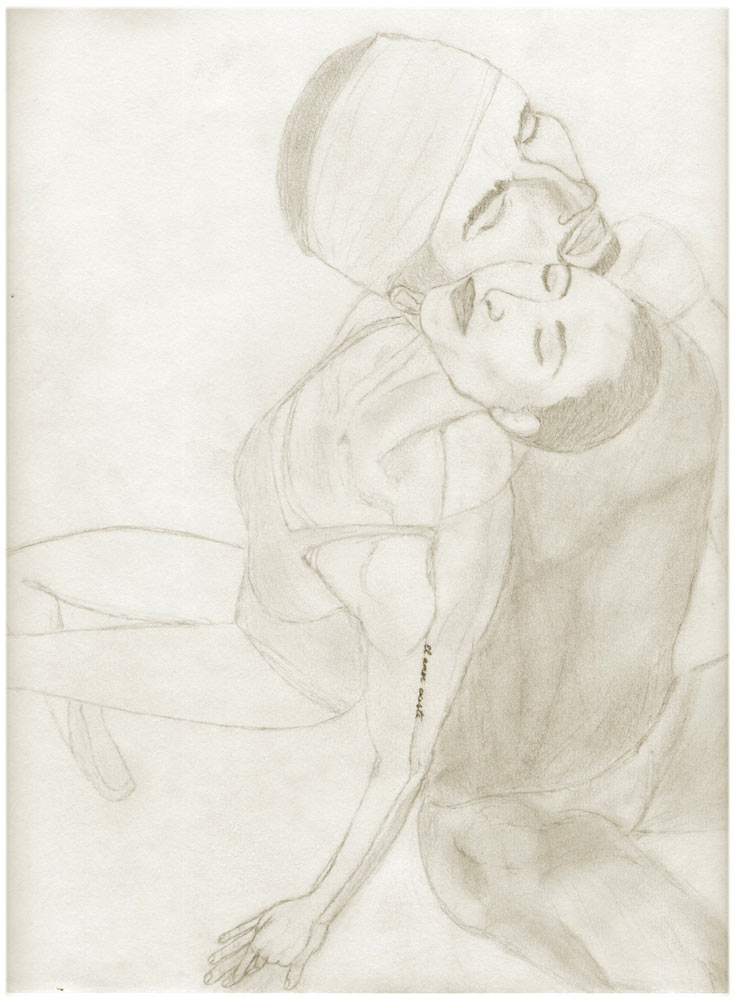

© Herman Cornejo.

Do you have other passions outside of dancing that sustain you when you aren’t in the studio?

Well, I like to draw. Hands and faces, mainly. I never took lessons; I just started drawing one day and I was kind of surprised at how well it came out. I guess it’s a hidden talent.

What roles are still on your wish list?

Swan Lake, which I’ll dance at the Met next season with Cojocaru. Onegin. Des Grieux in Manon, though I love dancing Lescaut. Lescaut is such an incredible role, with so many facets.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

What do you know about the rest of Ratmansky’s Shostakovich trilogy?

I asked him, after the première, there is so much in this first part of the trilogy [Symphony No. 9], what’s left for the other two ballets? We’ll see.

Have you ever danced at the Colon Theatre in Buenos Aires?

Well, I was invited to a gala there earlier this year, but not by the ballet company itself. They’ve never asked me. It’s actually quite painful, because I studied there, and I’ve never been asked. And now I’m 31, and you know, if they ask me years from now, I don’t know if I’ll want to; I don’t want to go there and perform once my technique is eroding. The window is closing. Of course, if they asked me, I’d probably be so happy I’d go anyway.

© Herman Cornejo.

I should have mentioned: The interview was conducted in Spanish and subsequently translated into English.

Cornejo is an example of how Argentina, with its culture of envy, hates its best people.

[…] my interview with Herman Cornejo appeared in DanceTabs, the photographer Lucas Chilczuk contacted me. Turns out […]

Having been an admirer of Herman Cornejo for some time, I am very happy for the opportunity to now have the opportunity to see him dancing a wider range of roles,especially roles that will make use of his first rate acting ability. I found myself often arguing over the height issue. How exciting to see him dance with a wide range of superb ballerinas in major roles. I congratulate him and wish him the best oif luck on what is almost a new career.