© Jorg Baumann. (Click image for larger version)

This Insubstantial Pageant

Kidd Pivot

The Tempest Replica

New York, Joyce Theatre

28 November 2012

kiddpivot.org

www.joyce.org

The Canadian-born choreographer, Crystal Pite, is a master of illusion. Like certain directors (Robert Wilson comes to mind), no aspect of the world she creates onstage escapes her attention. Her dances are as self-contained and enveloping as movies, each element shaped and manipulated for maximum impact: lighting, projections, shadow play, ambient sounds, text, costumes and, most of all, the movement of her extraordinary dancers. As in dance forms like jookin’ or breakdance, the eye is amazed by the mechanics of the body: it is as if Pite had pulled the human form apart to analyze how it moves, and then, with that knowledge, built a beautiful replica, endowed with an extended range of motion. The dancers don’t quite move like people, but rather like bewilderingly virtuosic, soundless cyborgs with joints that bend in unnatural ways. They glide, they jolt, they jigger, they pivot; even when dancing with each other they seem to carry their own weight, effortlessly (and weightlessly) to fold and flip in each other’s arms. One marvels at their abilities, but the effect is eerie, like human puppetry – what are these strange beings, and where do they come from?

© Jorg Baumann. (Click image for larger version)

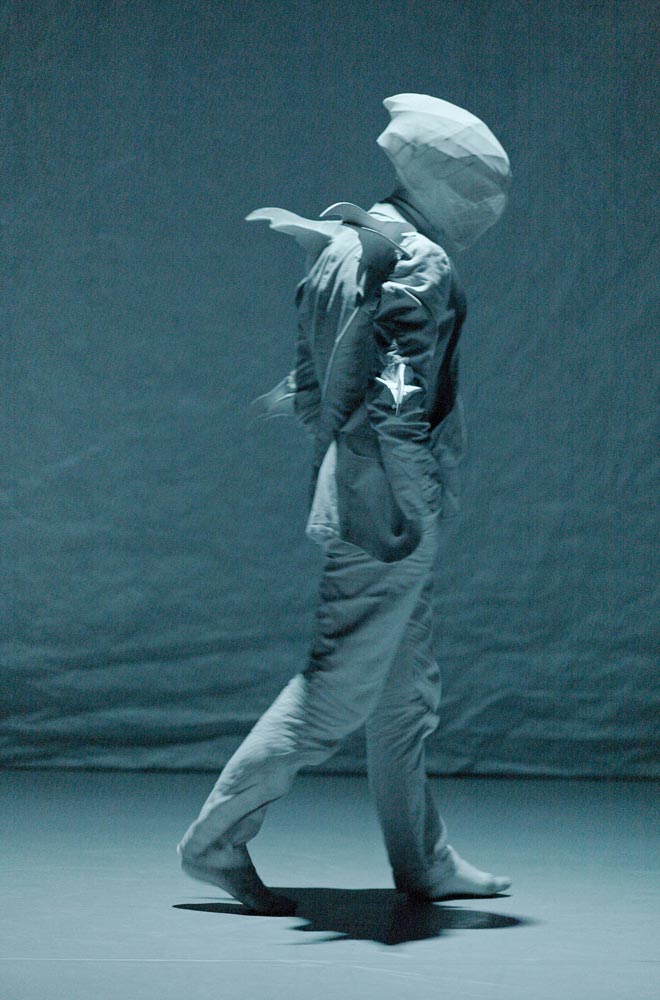

In The Tempest Replica, her latest invention to come to New York (the last one was The You Show, earlier this year), she takes on Shakespeare’s Tempest. Over the course of an hour and a half the story is told, more or less, twice: first in swift pantomime (aided by projections) and then in a series of more intensely danced interludes. As one enters the theatre, a slight man in everyday clothes (Eric Beauchesne) is folding origami boats and setting them on the stage. He is Prospero. Behind him hangs a semi-translucent curtain. The lights darken, and he anxiously cries out: “Ariel! Ariel!” A figure appears (Sandra Marín García), tall and lanky, clad in gray. Beauchesne places a paper boat in her hand and quietly commands: “shipwreck.” García’s arm undulates, like a guitar string in slow motion. As when one watches puppet theatre the eyes adjust and the illusion comes to life. Then, abruptly, García stuffs the boat into the gaping hole of her mouth, accompanied by a loud roar in the score. The mundane becomes monstrous.

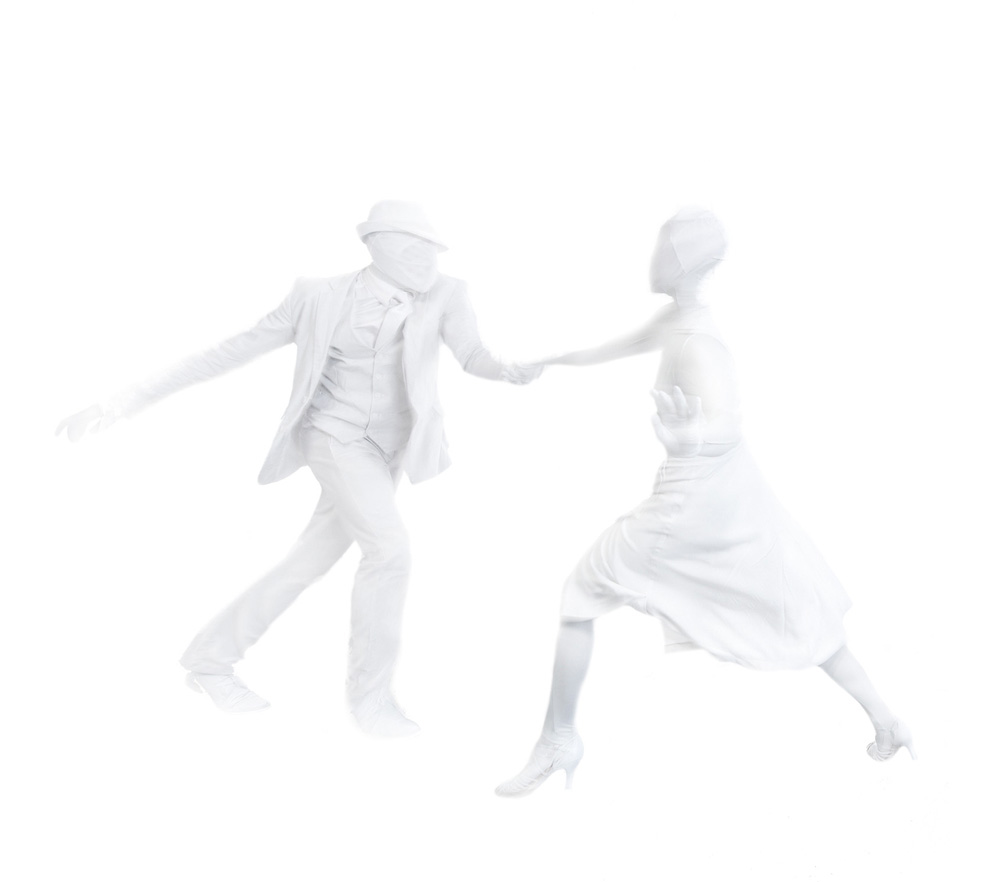

In this first section, Pite tracks the events of The Tempest quite faithfully, aided by animations and surtitles, cleverly projected onto a character’s dress, an unfolded piece of paper or the parchment-like back curtain: “Act one scene two: Prospero’s daughter sees shipwreck,” etc. The choreographer recently told an interviewer (Janet Smith): “I would love if every audience member that came to see it knew The Tempest, but that’s of course not true. So I thought, ‘Let’s tell it through an on-stage storyboard, with figures that are like the plastic people in an architectural model.’” She sheathes her dancers from head to toe in white, including strange ovoid head-coverings that make them look like aliens or attractive computer-generated figures in a video game. Select details – a stylized crown for King Alonso and a dragon-like crest for Caliban – identify the faceless characters. Garcia, in particular, does not seem quite real: her white superhero outfit and high heels accentuate her improbably lean, Barbie-doll lines as she flicks her fingers or walks with exaggerated articulation, shape-shifting like a Transformer.

© Jorg Baumann. (Click image for larger version)

The story rolls along: a spectacular reenactment of the opening storm and shipwreck; the meeting between Prospero’s daughter Miranda (Cindy Salgado) and the shipwrecked Prince Ferdinand (Jermaine Maurice Spivey); the plotting of Prospero’s enemies; the violent, salacious dreams of the dragon-like Caliban (Bryan Arias). Prospero’s past is revealed through the device of cartoon-like animation, accompanied by tinkly music (one of a few sentimental touches in the show). The play’s themes – Caliban’s resentment, Miranda and Ferdinand’s rapturous attraction, King Alonso’s treachery – are developed in the second half as individual portraits. These are performed in street clothes and set to everyday sounds or noises produced by the dancers themselves (yelps, grunts, sharp intakes of breath). Many of the pas de deux are intricate combat sequences, with bodies swirling and gliding across the floor (in socks), or throwing each other as dazzlingly as actors in a kung-fu movie, but without the help of special effects. (These superhero-style battles were a feature of The You Show as well.) One marvels at the dancers’ precision and articulation and at their utter concealment of effort; these sequences must have taken months to perfect. Bryan Arias’s portrait of Caliban, in particular, is a masterpiece of sinister, slithering, flickering motion. Jermaine Maurice Spivey performs a gasp-inducing solo in which he launches himself into the air and flips and spins, then lands weightlessly and revolves, seemingly in slow motion, on one leg, his upper and lower body moving at different velocities, creating a stunning torque. Pite’s dancers are the ninjas of the dance world.

All ends well, with a happy couple and Prospero’s pardoning of his enemies. As the lights dim, these once sinister men, again clad in white, release the magician from his unearthly powers by applauding in silence. The idea comes from Shakespeare: in Prospero’s final soliloquy, he beseeches the audience to release him from the bonds of illusion “with the help of your good hands.” The metaphor of theatre as chimera – in Prospero’s words an “insubstantial pageant” – and of the artist as a conjurer clearly appeals to Pite. (And it’s a good thing, because this season she worked on yet another Tempest, creating the choreography for Thomas Adès’s Tempest at the Metropolitan Opera.) Pite told her interviewer: “I was really drawn to the higher themes of the play: it’s about a creator, a magician, Prospero, trying to reconcile his art and work with his family.” The artist and his creation; it’s a theme she has treated before, in Dark Matters. In that production, one of the main characters was represented by a bunraku puppet. Does she see the stage as a kind of elaborate marionette show? Perhaps.

© Jorg Baumann. (Click image for larger version

This, in turn, may be the show’s greatest weakness. It’s clear that Pite is a highly-skilled choreographer with sophisticated imagination and the means to give it physical form. And yet, there is something unsatisfying about the show. It creates an elaborate surface, but engages the mind and the heart less than it should. Yes, The Tempest can be read as a metaphor for the illusion of the theatre – an attractively post-modern idea – but what makes the play interesting is that it can be experienced on many levels, the seeds of which are planted by Shakespeare. Of course dance, even in the hands of a maximalist like Pite, has its own logic, less complex than words perhaps, but potentially just as powerful. I couldn’t help feeling that Pite’s use of the play, however refined in the details, was opaque at its core. Its storyline seems to serve mainly as an architecture upon which to hang her experiments in movement and stagecraft. Almost any story with fantastical elements would have worked just as well. As a result, the viewer is visually stimulated, perhaps moved by the dancers’ prowess, but not much more than that.

You must be logged in to post a comment.