© Dancetime Publications. (Click image for larger version)

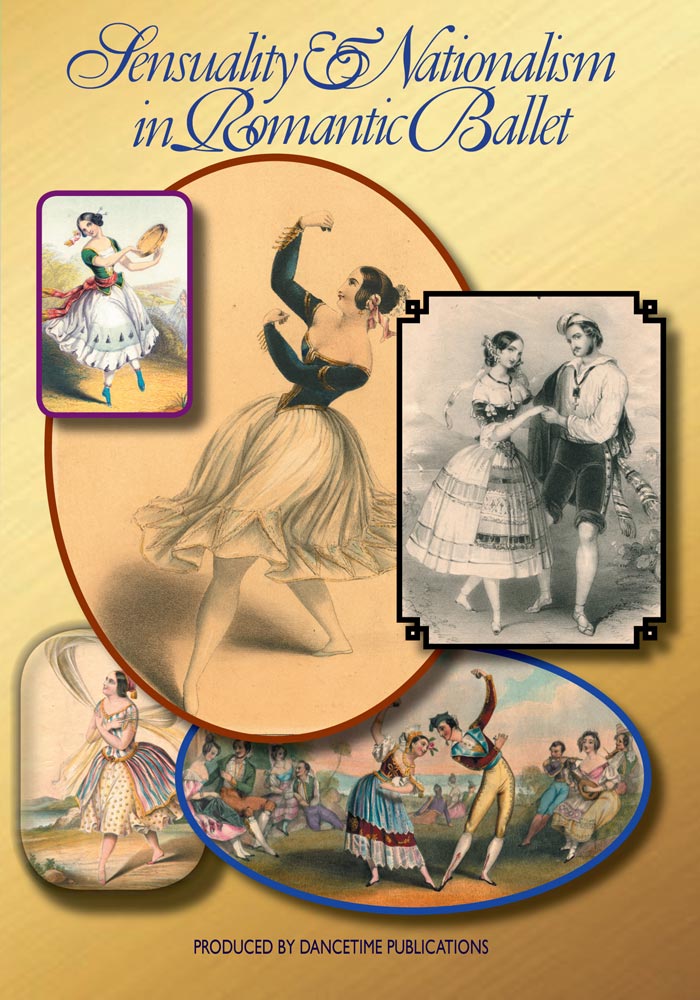

DVD: Sensuality & Nationalism in Romantic Ballet

Written by Robert Atwood and Claudia Jeschke

Running time: 57 minutes

Price: $49.95 by mail-order from the publishers

Dancetime Publications

Today, ballet is a slave to popular opinion, perhaps more than ever before. State funding for the arts continues to diminish around the world and although some of this income is being replaced from private philanthropy, no company can survive by regularly presenting ballets that fail to meet box office targets.

The inevitable outcome of this economic reality has been to rely upon the staple classical repertoire, albeit augmented from time to time by the occasional obligation to make something new. In companies all around the world, the most popular ballets stem from the same original source that was nurtured over just five years in late nineteenth century St Petersburg where the fusion of many great talents – led by Tchaikovsky and Petipa – created three works that still remain the world’s most popular representations of the art. These are, of course, The Sleeping Beauty (1890), The Nutcracker (1892) and Swan Lake (reworked by Petipa and Ivanov in 1894).

The earlier decades of the nineteenth century had been dominated by another ripe period of creativity, enriched by the social and cultural influences that defined the Romantic period, with its fascination for the supernatural, the mystical and the exotic. Romanticism spread through society and culture in painting, architecture, literature and music. But whereas in every other branch of the arts the output of the Romantic era is still widely accessible today, the ephemeral nature of dance means that almost everything from that period has been lost. Even the most ardent connoisseur of ballet is likely only to have experienced the rich heritage of the Romantic epoch through its two great survivors: La Sylphide (1832) and Giselle (1841), remnants of a golden age that transformed the art of ballet and which have come down to us through history by retaining a worldwide performance appeal.

This well-conceived and succinct DVD is based on original research by Professor Claudia Jeschke of the University of Saltzburg with a text that was written by both her and Robert Atwood, edited by Stuart Math and produced by the specialist US Company, Dancetime Publications. It provides a succession of brief and fascinating insights into Romantic Ballet with a text that achieves a successful balance between retaining an academic approach to the subject while still providing informative access to anyone with a strong interest in the evolution of dance. The larger part of the DVD is taken up by a series of seven compact chapters, small but perfectly formed capsules of narrative, some of which are sub-divided into separate themes, each focusing on different facets of developing the Romantic concept in ballet. Each chapter is illustrated by contemporary engravings and pictures (drawn from the clearly remarkable collection of dance images in Salzburg’s Derra de Moroda Dance Archives, of which Professor Jeschke is the director/curator) and by well-placed snippets of restaged dance steps. It is narrated by Atwood, Math, Michele Rafic and Carol Teten (the founder of DanceTime Publications).

© Courtesy of the Derra de Moroda Dance Archives, Salzburg.

The concluding part provides the complete versions of six restaged dances that few will have ever seen before, the choreographies spanning a century from 1761 to 1859, although the total dance time for the six pieces is only a little more than 20 minutes. These restaged dances added greatly to my understanding of how dance technique and fashion developed through the late eighteenth and early to mid-nineteenth centuries. One benefit of the DVD to any researcher or student is a menu that enables the viewer to select any part of the narrative or particular dance that they wish to see.

It is a pity that I strongly disagree with the opening statement in this otherwise excellent DVD, where, against the background of several evocative drawings of sylphs, the narrator introduces us to the topic of ‘Sensuality and Nationalism in Romantic Ballet’ by saying “When people think of the nineteenth century dance, they usually think of the white ballets of the Romantic period”. Anyone who appreciates the vital importance of the Romantic era might perhaps believe this to be true but on the contrary, and for the reasons I mention in the opening paragraphs, I expect that the general ballet-going public will think first of those three ballets born at the very end of the nineteenth century in Imperial Russia, during the later classical period, which is why they continue year-after-year to see them with such an undiminished fervour.

The DVD shows us images of ballets that were just as popular as Giselle in their day and concerned very similar subjects, such as Le Papillon (1860), a fantasy ballet by Marie Taglioni to a score by Jacques Offenbach, which is illustrated by an etching that could easily have been a woodland scene from La Sylphide. But it also strives to show that there was more to Romantic Ballet than merely “doll-like poses and stories about sylphs and fairies”.

The introduction progresses to explain that the beginning of the Romantic era “reflected a period of dramatic change in artistic perspective…a period in which people’s ideas about themselves and the world around them were revolutionised”. And it is true that the earlier years of the Romantic period (the decades that bridged the 18th and 19th centuries) were more concerned with material issues in the real world rather than the supernatural. This is perhaps best seen today in the matters of landowning inheritance and marriage that dominate that other great surviving narrative of La Fille mal gardée (dating from 1789). This grounding in reality can also be seen in the first act of Giselle with its focus on a day in the life of fieldworkers and hunters, centred upon the village folk rather than the aristocracy; all bound up in the age-old tale of a romance that crosses this impenetrable social divide (even if it does so unknown to the deceived and innocent village girl). It is worth noting that although we first encounter Albrecht, this story is all about Giselle and Albrecht’s role is only defined in relation to her.

By the late eighteenth century, the almighty power of the church in Rome and the divine rights of monarchies had been well and truly challenged. This tumultuous era led to the rise of constitutional rather than “God-ordained” power and many countries became defined by issues of national identity rather than by their ruling families. Also, the growing vitality of business and trade created a bourgeoisie that needed to be entertained. These factors led to a change in the way that ballet was presented: as public entertainment in theatres rather than for the private pleasure of the aristocracy.

Audiences for ballet had therefore diversified to include a much broader range of society – led by the rapidly changing social strata in post-revolutionary France – and so it was essential for theatrical productions to achieve a new level of communication with their audiences by developing a greater association with popular culture. This can best be seen in dance leaving the elegance of a formal indoor setting for codified structures and steps, moving “outdoors” with a focus on popular rustic dances of celebration, such as can be seen in the first act of Giselle. Another example shown here is a solo from Cachucha – first performed by Fanny Elssler, the epitome of Romantic ballet, in 1836 (but restaged here from notations that date to 1871).

© Courtesy of the Derra de Moroda Dance Archives, Salzburg.

As indicated in the DVD’s title, an increasingly essential aspect of this period was to establish new national identities for ballets and the characters portrayed within them, thus reflecting the wider changes taking place across Europe. In ballet, this cross-pollination of influences was carried by the proliferation of nomadic guest dancers and ballet masters, helping to establish an international phenomenon that had stretched across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas by the early nineteenth century. This is well illustrated in the DVD by a lampooning cartoon of Elssler (shown in her Cachucha costume) drawn en pointe, standing on a map of the world, with one set of toes balanced upon Paris and the other on New York, while holding a sack of money in each hand, the left-hand loot clearly marked as dollars.

Identifying a character’s nationality became a shorthand reference that “helped define to the audience aspects of her personality”. As the narrator continues, “In essence, national dance became the medium through which human characterisation on stage was made possible”. This growing emphasis on nationalism was also bound up with an increasing fascination for the exoticism (even perhaps, the eroticism) of faraway cultures, which came to provide characters, themes and settings for theatrical works, including ballet.

The DVD also focuses on the synthesis of ballet technique that evolved from crossing the traditional boundaries of ballet, particularly in the marriage of the styles that had emerged in France (devoted to the ideals of courtly decorum and formal, patterned structures in using the floor) and Italy (more expressive, dramatic gestures and athletic movement). This marriage of styles had begun in the mid-18th century in the work of Jean-Georges Noverre (1727-1810) and Gaspero Angiolini (1731-1803), each separately developing a mutual concept of the ballet d’action, which changed the nature of dance steps, making them more expressive, shifting the emphasis of ballet to the “dramatic content of movement”.

The DVD acknowledges this key step in the evolution of ballet by specific reference to the example of Angiolini’s collaboration with the composer Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787) in staging the pantomime ballet Don Juan (ou Le Festin de Pierre), which premiered in Vienna in 1761. Don Juan is now considered the seminal work of the ballet d’action and Gluck’s score was “ground-breaking in its expressiveness and its capacity for story-telling”. Don Juan also related a story of Spanish origin through national dance material that was designed by Angiolini to express both story and character and this is illustrated through a restaging of a Fandango from the ballet, based upon Gluck’s own manual to which had been added movement notations for rehearsal purposes.

This Austrian work by an Italian choreographer and a Bavarian composer based on a Spanish theme is followed by a similar example of the French School through a brief excerpt of Vestris Gavotte (1832), which shows the marriage of stylistic deportment (especially in the upper body) with the speedy athleticism of light, quick and elegant steps. Essentially, the Vestris Gavotte provides a bridge between the techniques exemplified by Gaetano Vestris (1728-1808) and his son, Auguste (1760-1842): the clear geometrical structure of the dance and precise harmonies of the dancing couple reflect the earlier period of Gaetano; and the allegro virtuosity of the steps and the consequent stamina required by the dancers exemplifies the “personal talents and achievements of the younger Vestris”. The narration goes on to show how this synthesis of material from the French and Italian Schools of dance is encapsulated in the vocabulary of the allegro variation in the first act of Giselle (although for illustrative purposes this is danced here as a solo for the male dancer in the character of Albrecht).

The DVD then moves on to show how the Romantic era shifted the focus from the architectural patterns of the dance in its use of the floor space to the development of character and story-telling through movement, often linked to the individual performance qualities of particular dancers. The great artists of the Romantic era became known for particular signature dances that best reflected their individual qualities of technique and expressiveness.

Further chapters deal with other issues central to an understanding of Romantic ballet such as the creation of ‘Couleur Locale’, which means establishing a sense of national location through stereotypical associations of design, costume and gesture, which were often more evocative than they were accurate! This section is illustrated by the Tyrolienne duet by Henri Justamant (1859), which has never before been seen by anyone still alive. ‘Expressiveness’ is considered through the more co-ordinated use of the upper body, illustrated through Albrecht’s second act entrance on the way to Giselle’s grave and the way in which his subsequent variation in the second act pas de deux is transformed from being pure dance by the character’s permanent awareness of both Giselle’s grave and the ethereal presence of the Wilis.

© Courtesy of the Derra de Moroda Dance Archives, Salzburg.

The significance of the ‘Spanish Repertoire’ in Romantic Ballet merits a sub-chapter of its own and is also illustrated by an example from the choreographies by Justamant in a solo for the character of Esmeralda in his ballet Quasimodo (ou la Bohémienne) (made in 1859) and from which the Tyrolienne duet is also taken. Justamant’s work is now sadly long-forgotten by all but professional dance academics and has never been presented to the public in living memory, although he left fully notated scores for more than 100 ballets and divertissements. The stereotyping of national identity throughout the Romantic period is demonstrated by the notable similarity of style and step formation in the Spanish dance examples, which span almost a century, from Angiolini’s Fandango (1761), through Cachucha (1836) to Justamant’s Pas de Esmeralda (1859).

The final chapter examines various aspects of transforming the ballerina’s art during the Romantic era. This looks at the use of the veil, the arabesque and floor space in Romantic ballet. The sub-section on the veil includes many sketches from the Opfermann family – dancers working in Germany and Austria in the mid-19th century – who left a sketchbook of ideas for the use of veils in ballet, including many variations of the sculptural potential for swinging and folding the fabric, thus extending the dynamic range of the dancer’s movements.

The Romantic period brought innovations around the concept of balance which contrasted with the stately and erect carriage that had characterised movement in eighteenth century ballet. The Romantic period developed the dynamic possibilities of moving in and out of balance, as embodied by the use of the arabesque. In the era of Romanticism the arabesque was more an expression of the natural world – a spectacular transition to represent the bending of a flower stalk, for example – or as an expression of national dance identities (such as Arabian dance from where the term originates) than it was to describe the formal set position of ballet technique that it was to become later in the nineteenth century. The innovations of Romantic Ballet also included the notion of falling to the floor to create theatrical impact and emotional power, a device that is, of course, used to significant effect in Giselle.

Femininity is a crucial feature of Romanticism. The Romantic period was perhaps more than anything else the era of the ballerina. Choreography and costume design concentrated the impact of movement, certainly in more provocative terms than ever before, on the female form. Changes to the costuming of ballerinas during this period enabled them to raise their legs higher, thereby creating visual lines that “would have been unacceptably risqué in an earlier era”. The use of fabric became a key part of the developing sensuality of dance through the Romantic period, which is well illustrated here through the Pas de L’Abeille from the ballet La Péri (1843). This dance depicts the Péri – a supernatural girl – disturbing a bee when plucking a rose, which then gets caught up in the fabric of her dress. The ballet critic, Théophile Gautier wrote the libretto for La Péri and his record of the dance describes how in trying to escape the bee she removes the fabric and accidentally reveals her body.

This focus on story-telling coupled with a new freedom in costuming and a new dynamic in movement and the use of the veil created a shift towards sensuality, which made the woman dancer the central active force in ballet. But this renewed focus on the woman was not just a matter of erotic titillation, since the Romantic period created a new dependency on the woman’s execution of demanding and virtuosic material. An examination of Justamant’s notations for Quasimodo shows that the most technically difficult material in the ballet is given to the character of Esmeralda.

The restaged dances begin with a one-minute Fandango solo from Angiolini’s Don Juan (ou Le Festin de Pierre), originally created in 1761. The reconstruction is based upon the publication of Gluck’s annotated performance scores (by Sibylle Dahms and Irene Brandenburg in 2010) and the music is a piano reduction of the appropriate part of the Gluck score executed by the German musicologist, Thomas Hauschka. It is danced impeccably by Rainer Krenstetter, an Austrian danseur who won the Prix de Lausanne in 1999 and is now a soloist with Staatsballett Berlin.

Next comes the Vestris Gavotte (1m 53s), danced by Krenstetter and Nadège Hottier, formerly a ballerina with the companies in Bonn, Leipzig and Berlin and now ballet mistress at the French Academie of Ballet. It has been recreated from the notated score in E.A.Théleur’s Letters on Dancing, published in 1831. The music used has again been executed by Thomas Hauschka. Authentic costumes for this and three of the other works were provided by Lydia Harmom of Tutu Etoile. A casual observer of this piece would be forgiven for thinking it to be in Bournonville style.

© Dancetime Publications. (Click image for larger version)

The third reconstruction is the Cachucha solo made famous by Fanny Elssler in 1836, which is danced superbly by Hottier, complete with castanets and rose, every centimetre the Spanish señorita. The dance has been recreated by Ann Hutchinson Guest who coached Hottier for the 5-minute performance. Her reconstruction is based on the publication of a notated score by Friedrich Zorn in 1887. This DVD is worth owning for this little gem alone, although if I had a quibble it would be a minor irritation with the camera shots cutting randomly to close-ups of the feet or upper body and the dancer momentarily departs from the camera shot. Hutchinson Guest also provided the music. The Spanish costume for Cachucha was made by Dance Through Time.

Restaging number four is an extract from the Pas de l’Abeille (3m 32s) from the ballet La Péri, composed in 1834 by Jean Coralli and Théophile Gautier, which is danced seductively and daintily by Carolina Osopova of The Brooklyn Ballet in her long yellow veil. This is not a reconstruction but an approximation of the dance which follows the descriptions of the story and gestures written by Gautier. Some phrases in the step material have been derived from the written notation of veil dances recorded in Henri Justamant’s choreographic scores. The music used for this Pas de l’Abeille is another piano reduction executed by Thomas Hauschka from the original orchestral score by Joseph Burgmueller.

The fifth restaging is the energetic Pas de la Esmeralda (4m 20s) from the ballet Quasimodo (ou la Bohémienne), created in 1859 by Henri Justamant and reconstructed from his own written notations. The music is again a piano reduction executed by Thomas Hauschka from the original orchestral score by Joseph Luigini, as attached to the archived notation. Esmeralda’s dance is performed by Kerry Shea (also of The Brooklyn Ballet).

And the final restaged dance is the Tyrolienne (4m 49s), a pas de deux – also from Justamant’s Quasimodo (ou la Bohémienne), performed by Richard Glover and Christine Howard, again from the Brooklyn company. The camera work is poor in places and the two dancers are not always in frame but this duet contrasted against the Vestris Gavotte amply illustrates how the pas de deux developed into a more sensual and less stylised dance over the course of the Romantic period.

In addition to the six restaged dances, the DVD also contains extracts of Idomeneo Chaconne, conceived and staged by Sibylle Dahms and Claudia Jeschke and danced by Krenstetter; “Aus meiner Sicht” – a lecture performance about the part of Albrecht in Giselle, conceived and presented by Rainer Krenstetter and Claudia Jeschke and danced by Krenstetter (who seems to me on this small evidence to be a superb interpreter of the role); and the Opfermann Veil Studies as performed by the Manhattan Youth Ballet.

© Courtesy of the Derra de Moroda Dance Archives, Salzburg.

The general public may not recognise the opening statement that the white ballets of the Romantic era are the most recognisable product of nineteenth century ballet but this DVD certainly proves – if any proof were required – that the Romantic period transformed the performance of dance forever. As the narration concludes, there are “a multitude of influences that continued to evolve and shape ballet and many aspects of contemporary dance as we know it today”. Two centuries later ballet is still largely centred on the leading role of the prima ballerina. We can also trace this legacy beyond ballet: “Explorations in balance, weight, and dynamic transitions informed not only the development of ballet technique but also the new inventions of the early modern dance pioneers: echoes of the romantic period can be seen in the sculptured fabric of Loie Fuller; in the suspension and falling of Isadora Duncan; and in the floor work of Martha Graham”.

This is not by any means a DVD for casual viewing, but for the serious student of ballet it provides a concise and fascinating understanding of the key components of Romantic Ballet, hugely enhanced by the opportunity to see a group of restaged dances from that era that have not been seen before, which at one level provides an insight into the meaning of gesture and movement in Giselle; and on another clarifies this essential step in the evolution of ballet and dance, with many references that can still be seen in works that are being made today. The carefully restaged dances are to be savoured again and again.

You must be logged in to post a comment.