© Natalia Goncharova, courtesy Mikhail Baryshnikov and ABA Gallery. (Click image for larger version)

Baryshnikov Arts Center: www.bacnyc.org

ABA Gallery: www.abagallery.com

Old Friends — Works from the Collection of Mikhail Baryshnikov

On a nondescript block just off of Union Square, near a Hale and Hearty soup place and across from a parking lot, stands an unmarked eight-story building with fire-escapes zig-zagging down the front. You wouldn’t know it, but inside, on the second floor, there’s an art space, ABA Gallery, specializing in nineteenth and twentieth century Russian art. One afternoon two weeks back, the amiable, bearded man who owns it, Anatol Bekkerman, showed me around its two spacious rooms filled with landscapes, portraits, still lives, and the odd abstract canvas (including two huge drip compositions by Bekkerman’s brother, Edward). But I had come to see the works in the first room, none of which were for sale. It was the last day of an exhibit of works from the collection of the great Russian ballet dancer, Mikhail Baryshnikov. For the first time, at the insistence of his friend Irina Antonova, director of the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, he had agreed to show a significant number of the works he has picked up here and there over the course of his dancing career. The exhibit, which will travel to Europe, is called “Art I’ve Lived With,” and most of its contents have traveled from his house upstate or a few blocks down from his arts complex in Hell’s Kitchen, the Baryshnikov Arts Center. In his short catalogue essay Baryshnikov, whom everyone refers to as Misha, calls the works “portable friends,” companions he has “packed and unpacked” many times over the years and in many countries.

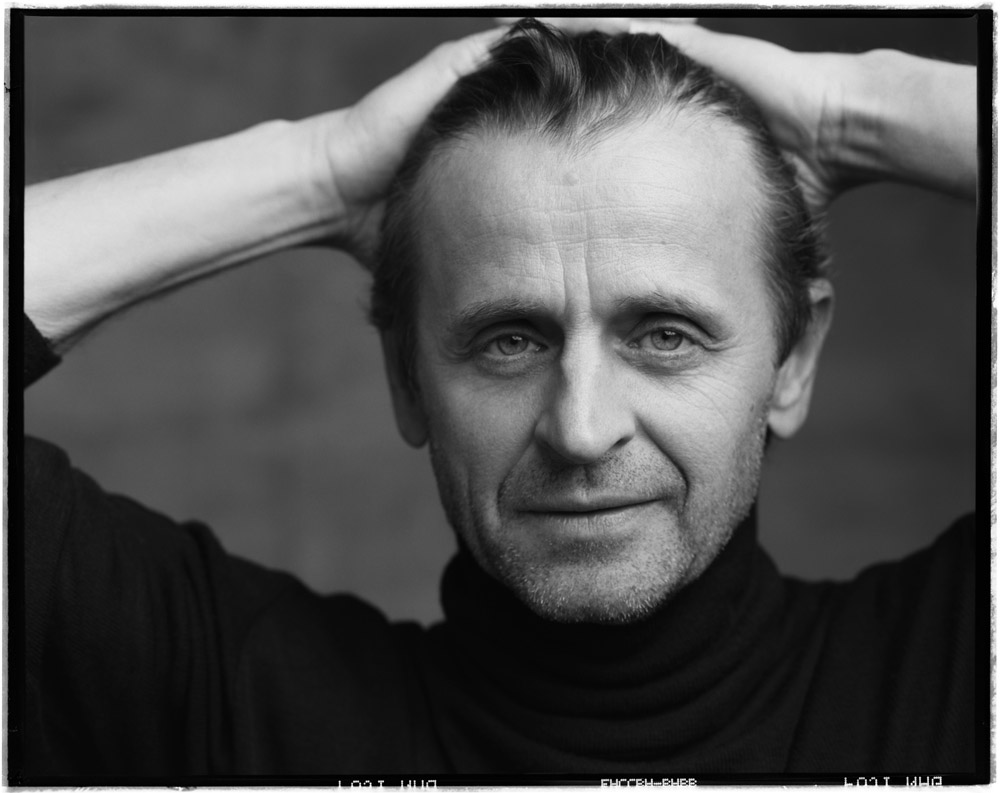

© Annie Leibowitz. (Click image for larger version)

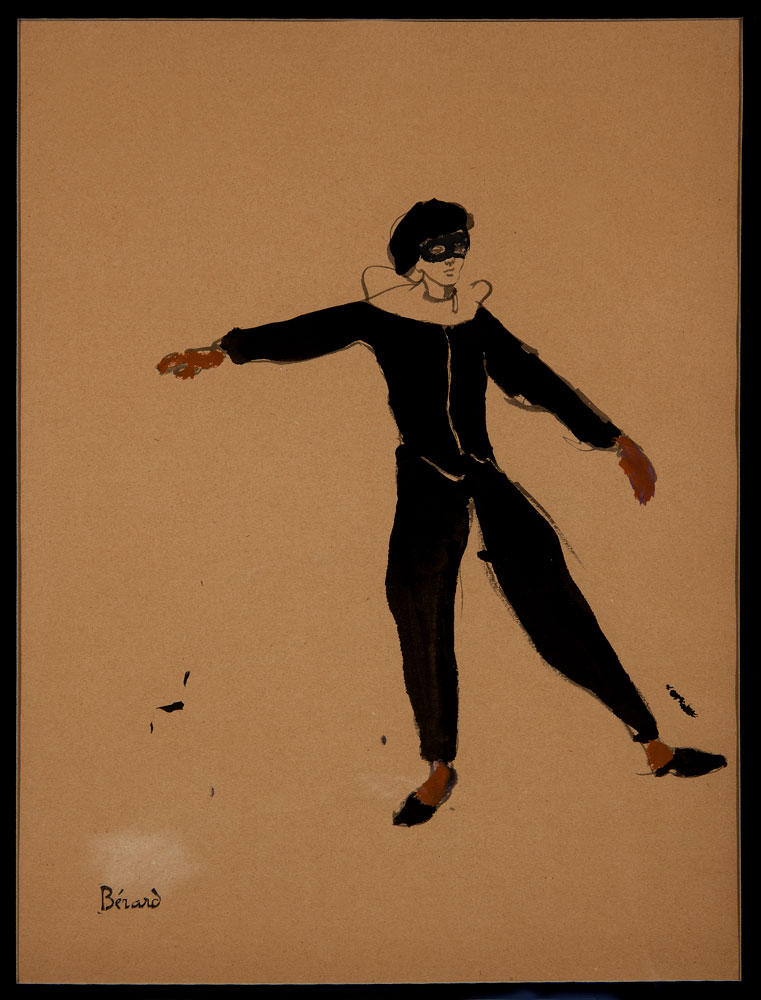

Misha strode into the gallery five minutes after the appointed time, trim and compact, sheathed in a knee-length leather jacket, a black porkpie hat on his head. He is no longer the boy with soft blue eyes that graced the bedroom walls of many a girl in the 1980’s, including my own. Somehow, he has grown wirier, tighter, more serious with age; what one senses more than anything is a sharp intelligence, an unwillingness to waste time. With a quick nod, he was down to business. This little collection, he told me, began with a simple purchase in Paris back in 1975, at the Galérie Proscenium on the Rue de Seine, on the left bank. Misha was twenty-seven then, and “the dollar was strong and I had money in my pocket,” he says, nonchalantly. Of course what he’s leaving out is that the year before he had defected while on tour in Canada with the Kirov Ballet, instantly become the most famous dancer in the world. One can imagine the sense of liberation, the feeling of being on top of the world and at the top of his game. On that winter day in Paris he bought two small works on paper, a Cocteau portrait of the Ballets Russes impresario, Serge Diaghilev (from 1917), and a Christian Bérard watercolor, a design for the original 1933 version of George Balanchine’s ballet Mozartiana. Both purchases make perfect sense. In the early twentieth century, Diaghilev had almost singlehandedly revitalized the art of ballet by producing shocking, fashionable, and often titillating works for the Parisian audience; several, like Spectre de la Rose and Prodigal Son (by Balanchine) would become signature roles in Baryshnikov’s career. (Surely Baryshnikov, with his famously sailing jump, must have identified with Nijinsky, who was said to be capable of covering the space from center stage to the wings in one leap. Misha’s collection includes a few images of Nijinsky, including a gorgeous bluish sketch by Valentine Gross of the thick-thighed dancer in Spectre, in which he played the essence of a rose.) As for the Bérard Mozartiana sketch, Balanchine was the choreographer Baryshnikov most wanted to work with after he left Russia; he even joined Balanchine’s company for a while, but by then the choreographer was too old and frail to make a new ballet for the young Russian star who had landed before him.

Baryshnikov’s first two purchases set a course for his collecting, which has tended toward small, elegant pieces, often with some connection to the world of the theatre, easily transportable, intimate in scale. The Diaghilev portrait is composed of just a few lines, really, a monocle, a tiny mustache, the suggestion of a double chin. Just as spare, in its way, Dufy’s pen drawing, “Portrait de Femme” (1930), reveals an appealingly open face with almond-shaped eyes, a frank expression and a mess of curls. “I just fell in love with this woman,” Misha says affectionately, as we pass her. The works seem to range from about six by nine to roughly two feet by two feet (one of the largest is an undated Goncharova pastel, “Untitled,” illustrating a trio of slightly grotesque, cold-looking faces on a Russian evening). “Kind of human size, so you can put them behind a chair, behind a lamp, behind a couch.” As he tells it, Baryshnikov favors walls covered in art, floor to ceiling, “like Gertrude Stein, from here to here” – he says, pointing to a wall – “full of photographs and art. In Russia we call it carpet-style.”

Almost a full wall of the exhibit is devoted to costume designs, many by Alexandre Benois, one of the original members of the art movement Mir Iskusstva and a close friend and collaborator of Diaghilev’s. Arranged in tight rows are designs for “The Nutcracker,” “Giselle,” “Petrouchka,” – all of which Baryshnikov danced – and various operas, many with notes in Benois’s hand detailing colors and fabrics: “soie,” “satin,” “astrakhan,” “velours agrementé de rubans.” One even has two tiny fragments of blue cloth attached to one corner. Amid this multitude, there is a sketch by Eugene Berman of two costumes for the Romeo in Antony Tudor’s ballet “Romeo and Juliet.” (It was first performed by American Ballet Theatre at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1943.) Where was Juliet, I asked? It turned out she was hanging on the other wall, demure in her Botticellian dress. Even here the lovers gazed at each other over a boundless divide.

As we walked down the line, Baryshnikov straightened a couple of skewed frames, quipping “the wall is dancing.” It’s clear that line and balance are important to him. A series of works by the Russian Non-Conformist painter, Alexander Arefiev, caught Misha’s eye. The colors are bold, set off by thick black outlines. The figures have no faces. “They break my heart, these images. The tension in those figures. She’s crying and he’s trying to manage the situation.” We move on. A Joseph Brodsky drawing (“Shore Leave”) of three soldiers and three women – remember “On the Town”? – reveals a secret, a second drawing on the back, with eight more sailors standing around near the dock. A dog sniffs at their feet; one of the boys takes a leak. There are several marvelously expressive portraits by Serge Sudeikin, including one of a doe-eyed boy with dark hair and shy, expressive lips. According to Misha it may be a portrait of the young Léonide Massine, one of Diaghilev’s protégés, who went on to become a major choreographer, and to appear in the 1948 ballet cult classic, “The Red Shoes”. Baryshnikov points out several gifts from friends, like a pen and pastel of birds and insects by Merce Cunningham, dedicated to Misha after the two performed Cunningham’s “Occasion Piece” in 1999. And a little drawing of a chaotic ballet rehearsal by Mikhail Larianov, a gift from Jerome Robbins after he created the Russian-inspired suite, “Other Dances”, for Baryshnikov and Natalia Makarova in 1976. A pair of feet, by Trisha Brown: “she stands and puts crayon between her toes and paints the right foot with her left foot and then switches. Standing up. Like this.”

What one does not see much of, at least at first glance, is nostalgia for the motherland. “I never had nostalgia about anything,” Baryshnikov says. But it’s there, if one looks hard enough. Its sweet fragrance wafts from a group of watercolors by Nikolai Lapshin, filled with a kind of pale, liquid, Russian light. In one, the Kazan Cathedral in St. Petersburg seems ready to dissolve into the thin wintry air; in another, a dark, craggy tree dominates the foreground, while behind it, hovering in the distance like a dream, we see a small city, Novgorod. The Russian soul.

What happens next? Hopefully, the collection will travel to the Pushkin Museum next year, as soon as funding is secured. Other European galleries have expressed interest. And what will happen when the paintings return? “I don’t know yet….I think because I’m showing it I feel that it’s the end. Its kind of complete. I decide definitely the collection is going to my center. What they do with this I don’t know. It will travel, then we’ll put it in boxes and in storage, because we don’t have enough places to display all this…. We recently moved from a bigger house to a smaller house, the kids are all gone to college.” So this is the end of his art-collecting, I ask him? “Probably, I mean, it’s the end of my life, darling. I’m almost sixty-five,” he says, flashing a boyish smile.

[…] Here is the piece I wrote for DanceTabs. […]

Dear Marina,

Thanks for your interesting interwiew, but I felt sorry, when Misha said, he is leaving, because of his age. Tell him, he is plenty of life and emotions, and certainly he has a lot of wonderful, and good things to show us.

Best wishes

Misha we love you forever.

Estela – São Paulo – Brazil

Thank you for reading and commenting…

You know, I think he was being playful when he said that. His mischievous smile made it clear to me that he know he was saying something provocative, and little bit tongue in cheek. He does not seem like that type to go in for self-pity!

After all, he’s still dancing, acting, and directing one of the most vibrant cultural center in NY…