© Erik Tomasson. (Click image for larger version)

Hamburg Ballet

Nijinsky

San Francisco, War Memorial Opera House

13 February 2013

www.hamburgballett.de

sfwmpac.org

It’s Valentine’s Day and I wish I could write a “love letter” review to the Hamburg Ballet. I am not being sentimental – this company is full of incredible dancers, from principals to corps de ballet; dancers who are exceptionally accomplished as technicians and artists, dancers who move well, individually and collectively, and ultimately, move me. How I would love to see them in a ballet other than Nijinsky, choreographed by their artistic director, John Neumeier, in 2000. This overly long and unrelentingly dramatic exploration, or perhaps exploitation, of the great dancer and choreographer, Vaslav Nijinsky, consists almost entirely of Neumeier’s own imaginings of how Nijinsky’s mind might have been awhirl with ghosts from his past lives, both on and off stage, as he lives inside his own convoluted head . Unfortunately, there is no perceptible method to the choreographer’s madness.

© Erik Tomasson. (Click image for larger version)

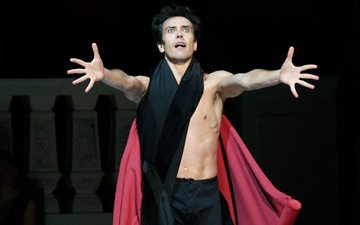

Neumeier has long been fascinated by mental illness, as I witnessed in his Illusions – like “Swan Lake” when it was first created in 1976. Danced to Tchaikovsky’s score and based on “mad” Ludwig II, King of Bavaria (who actually may not have been crazy), it deals with his confusion between fantasy and reality and ends with his suicide by drowning in a lake. At least the story is made clear, not like this Nijinsky, where attempting to decode the jumble of images is like trying to assemble a jigsaw puzzle without having the picture on the box to guide you. It doesn’t even help that I’ve read extensively on both Nijinsky and Diaghilev. Yes, I recognise all his dance roles – the Poet from Les Sylphides, the Faun, the Spectre de la Rose, the Golden Slave, Petrushka, Harlequin from Carnaval and the Tennis Player from Jeux – and an assortment of poses taken from photographs I’ve seen of Nijinsky dancing and with other people and dancers. But to what end has Neumeier tossed them together? How many people in the audience know to what they refer or why these specific people and his past roles matter? In fact, I find it rather a one-sided view of Nijinsky. Surely he is more than just a madman and could also be shown as an acclaimed performer and choreographer who descends into insanity instead of spending more than two hours flailing in a maelstrom of psychosis. In order for chaos to mean anything significant it needs to have the foil of clarity.

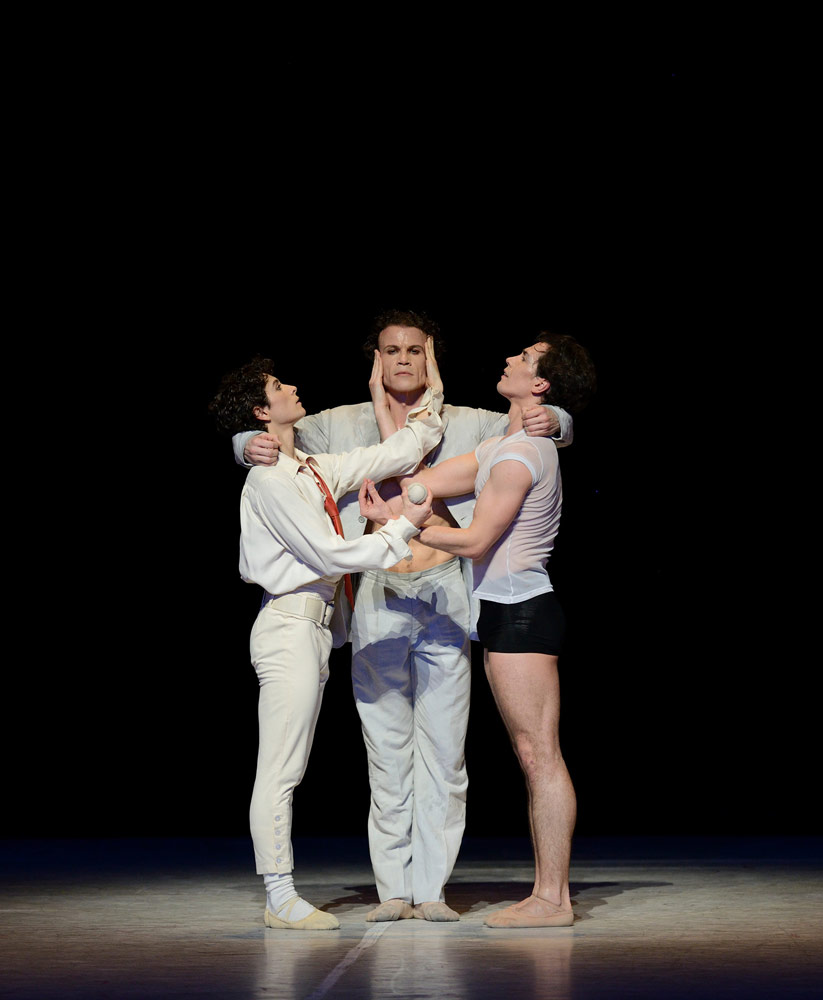

More irksome is watching all the various Nijinskys dance to Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherezade (first, third and fourth movements.) Since it would have been far too disjointed to have bits of the original music for each role, commissioning an original score that captured the essence of each ballet and could bridge all the styles successfully would be a solution. The other musical misstep is using Shostakovich’s powerful Symphony No. 11 for the second half, though it’s played very well by the SF Ballet Orchestra under the baton of the Hamburg guest conductor, Simon Hewett. The problem is that the war sections, both the First and Second World Wars, overshadow the rest of the dancing, except for the section of Nijinsky and his brother, Stanislav, danced stunningly by Alexandre Riabko and Aleix Martínez respectively. Neumeier also misses an opportunity to show Nijinsky’s brief period of normalcy when Russian troops reached Budapest where he and his wife Romola had spent WWII. Suddenly surrounded by his native language and fêted by soldiers who were incredulous to meet the renowned dancer, he emerged from his shell and joined in when the Russians played folk music and danced.

© Erik Tomasson. (Click image for larger version)

The sets, costumes and lighting are all first class, particularly the opening and closing scenes of the ballroom of the Suvetta House Hotel where Nijinsky gave his last public performance on January 19,1919 (all you numerologists can have a field day with that date.) The giant white rings that fill the space, behind, above and even rising horizontally from the floor recall Nijinsky’s obsession with the circular element of movement which he wrote about and drew prolifically in his diaries. The choreography, however, fails to illustrate these concepts and remains quite angular. Most of the ballerinas of the Ballets Russes wear costumes closely based on the originals except for the Chosen Virgin from Le Sacre du Printemps who, instead of being dressed in something resembling the primitive peasant dress designed by Nicholas Roerich, wears a nude leotard reflecting Neumeier’s own version of the ballet where she dances literally naked alone on stage.

There is a strange parallel between this ballet and the recent exhibition, Rudolf Nureyev: A Life in Dance, at the de Young Museum here in San Francisco. That show had little to do with the life and art of the defector from the Kirov and was mostly an excuse to show his own collection of beautiful costumes of the mid- to late-twentieth century. Some had been worn by Nureyev, but most were from ballets he had choreographed or staged for companies such as the Paris Opera Ballet, Teatro alla Scala, and London Festival Ballet. The name of the exhibition is just a marketing ploy to bring people in. Putting Nijinsky’s name on this ballet functions in the same way because most of the audience doesn’t come away knowing really much more about him.

© Erik Tomasson. (Click image for larger version)

By the final curtain I feel I’ve been machine-gunned with bullets made of images of this legendary dance icon, often without the benefit of an explanation or a logical narrative. I know that the Scheherezade music will play unbidden in my mind for a thousand and one nights like an advertising jingle. At least I will still see in my mind’s eye these exceptional dancers and hope they will return in the not-too-distant future.

You must be logged in to post a comment.