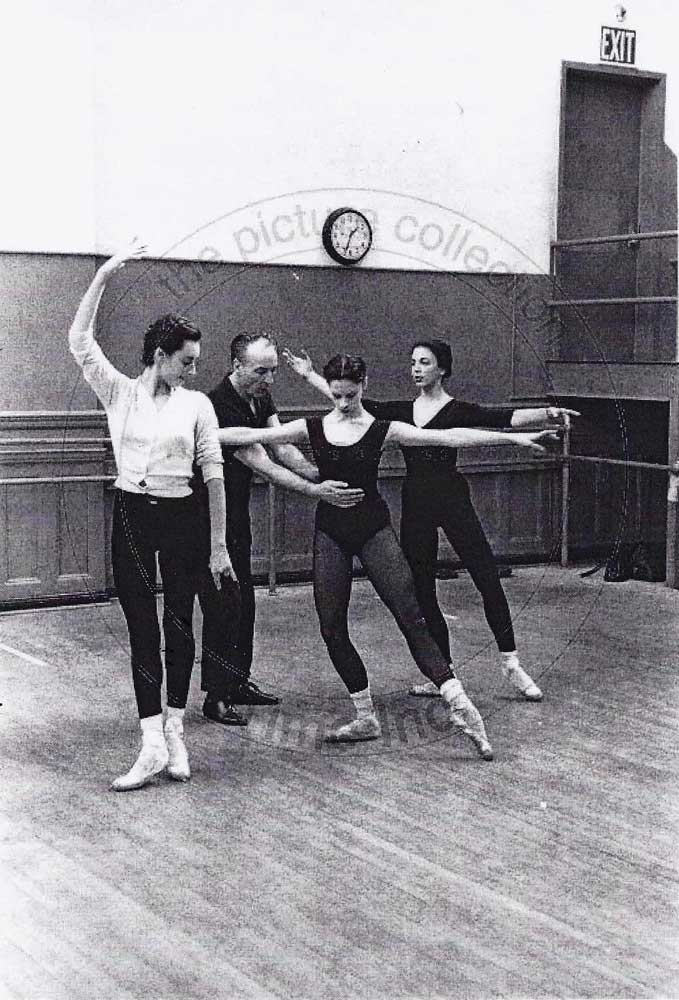

© Nancy Reynolds. (Click image for larger version)

Bringing Balanchine Back: An Interview with Nancy Reynolds

In one way or another, Nancy Reynolds’ entire life has been devoted to dance – much of it to the ballets of George Balanchine. As a young girl growing up in New York Reynolds decided that she had to become a dancer, much to the chagrin of her family, who considered the profession far too limiting for a well-rounded young woman. Her first ballet teacher was Tanaquil LeClercq, the leggy, cool New York City Ballet dancer who originated the role of Choleric in The Four Temperaments, the doomed central figure in La Valse, and the ballerina in Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun. In 1957 Reynolds too joined New York City Ballet. After five trying years, during which she struggled with her body and the all-consuming nature of the profession, she made the difficult decision to leave her youthful passion behind and go to college. She studied art history at Columbia and then began a new career in book publishing. Soon enough she was pulled back into the world of ballet by an opportunity no aspiring editor could possibly refuse: editing Lincoln Kirstein’s ballet tome, Movement and Metaphor. One thing led to another and she found herself immersed in a series of engrossing projects, from putting together Repertory in Review, a massively-researched compendium of New York City Ballet’s repertory from 1935-1976 (Serenade to Union Jack), to co-writing No Fixed Points, a nine-hundred page history of Western theatrical dance in the twentieth century. Along the way she wrote criticism, worked on the International Encyclopedia of Dance and directed research for Choreography by George Balanchine: A Catalogue of Works. Each of her books is an essential addition to any serious dance lover’s library.

Since 1994 she has undertaken a ground-breaking project under the auspieces of the The George Balanchine Foundation, the Balanchine Video Archives. The idea occurred to her one day while watching a dance performance. “What would we give to have seen Mozart coaching Don Giovanni?” she asked herself. The archive’s mission is to record working sessions with the dancers who originated significant roles in the Balanchine repertoire and conserve them for future generations. The project has two parts, the Interpreters Archive and the Archive of Lost Choreography. In the first, a dancer on whom Balanchine created a particular role – say Alicia Alonso in the case of Theme and Variations from 1947 – spends two days coaching a young performer, passing on the choreographer’s pointers and observations, filling in details that have been lost in the mists of time. In the second, a passage from ballet that has been lost – like the solo from Le Chant du Rossignol, made in 1925 – is recreated in the studio, again with the aid of its original interpreter. Since 1995, there have been over fifty of these sessions. The videos can be viewed at more than seventy libraries around the world (including the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts) and are also available to educational institutions for streaming, by subscription.

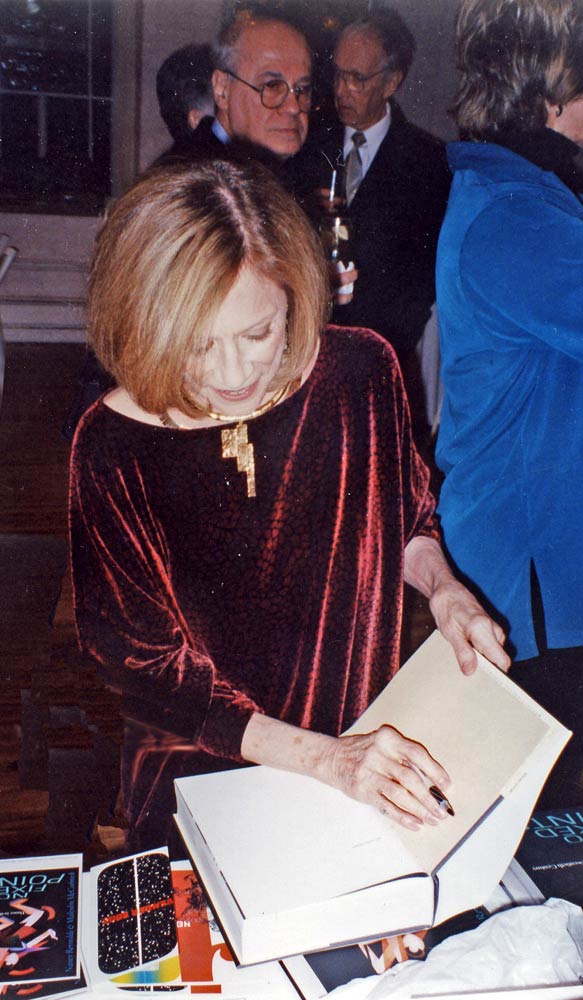

© Brian Rushton. (Click image for larger version)

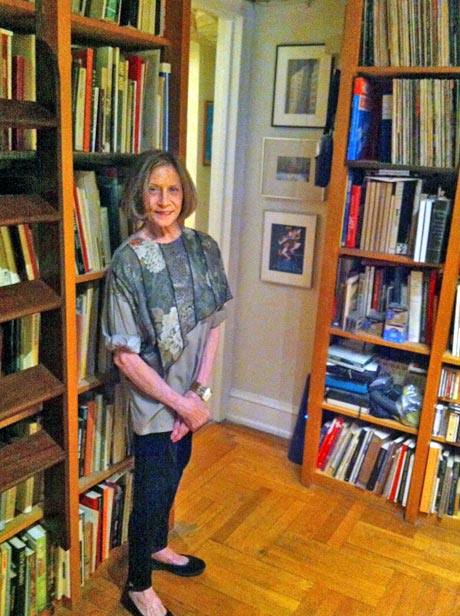

Nancy Reynolds and I spoke just before Christmas in her warm, book-lined apartment near Prospect Park in Brooklyn, just as the sun was beginning to dip behind the facades of a row of townhouses visible from her dining room window.

What’s your background and how did you come to study ballet?

I came to New York when I was ten, and have been here ever since. My parents separated when I was two – my father was stationed abroad during World War II. My mother was a New Englander and had always wanted to live in NY, so when their divorce became final, she headed here. I seem to recall my first experience of watching ballet, when I was about seven, was Ballet Theatre, and Les Patineurs was on the program. I believe John Kriza was the Boy in Green – he wore green in those days. The second time Sadler’s Wells came to New York I saw Fonteyn, Rowena Jackson, Nadia Nerina, and Svetlana Beriosova, and by that time I was beginning to get more and more interested in the ballet.

You also played the piano, didn’t you?

Yes, badly. I did the usual, three years of lessons.

When did you start taking ballet?

It was a total coincidence. I was enrolled in an after-school program at the King-Coit School, which offered a little dance, a little acting, and a little painting. We studied Duncan dancing. Tanaquil LeClercq’s mother was the receptionist and she said “I have a daughter who is a leading dancer with NYCB, and she’s never taught before and she’d like to give it a try.” So my first ballet lessons, about 40 minutes each, were with Tanny. As I look back it was absolutely amazing to have this gorgeous young teacher – she was about twenty-one then – who spoke excellent English. I say that because later on I had a lot of Russian teachers who had heavy accents and were way past it as far as being able to move goes. I don’t know what did it, whether it was studying with Tanny, or the fact that I happen to have very high insteps, but between the two, after about five months, I knew this was what I wanted to do.

© Fred Fehl. (Click image for larger version)

What happened next?

I think maybe those classes lasted about a year, but by the end of that year I was dying to study ballet intensively. I was twelve. By then I knew about the School of American Ballet. But SAB required attendance three times a week and my mother thought that was much too much. So we asked Tanny whom she would recommend, and she recommended Vera Nemchinova, who was teaching at Ballet Arts. I went once a week. By the end of that year I was insistent on going to SAB. And by then I knew who Balanchine was, and I’d seen lots of NYCB performances. I saw Tanny when La Valse was new. She asked me to come backstage and showed me her dress. As for the coat, she said, “Look at those jets,” [the stones decorating the dress] “I think Karinska got them off an old dress.” As you can imagine, I was over the moon.

What was she like?

She had a great sense of humor, and she was absolutely unpretentious, breezy, with nothing of the grande dame. She was sort of a cutup. She didn’t philosophize about dance, at least not verbally. She was down to earth and American, with no airs. A lot of that showed onstage.

How did you end up joining the company?

I had been at SAB for about five years. Balanchine was in Copenhagen with Tanny, who by then had come down with polio. I was an apprentice for the winter and then we went to Chicago and performed Nutcracker in the spring. This was followed by a six-month layoff and we didn’t start up again until the fall of ’57. That’s when I became a full member.

I’ve read that you were very unhappy in the company…

It was a huge disappointment. I was a poor technician; because I had high insteps and a flexible body, I wasn’t very strong technically. That was always a problem, so I was always frustrated. I felt unable to do justice to Balanchine’s ballets. Also, I didn’t like the life. I didn’t like all the hours spent waiting around and the fact that you never knew your schedule until the night before, and I didn’t like the dieting and all that body stuff. I didn’t like being exhausted and depressed all the time. So after a while I started to wonder, “why am I doing this?”

At one point, Balanchine sent you to the Martha Graham school to see if it might help strengthen your back. What was that like?

I remember skipping across the floor and doing some floor work. But for me the pursuit of ballet technique was simply all-encompassing, and anything that got in the way or used up my strength seemed very secondary. I remember going to Jacob’s Pillow one summer; we did Spanish dancing, Indian dancing, modern dance, calisthenics and ballet. I resented everything except the ballet.

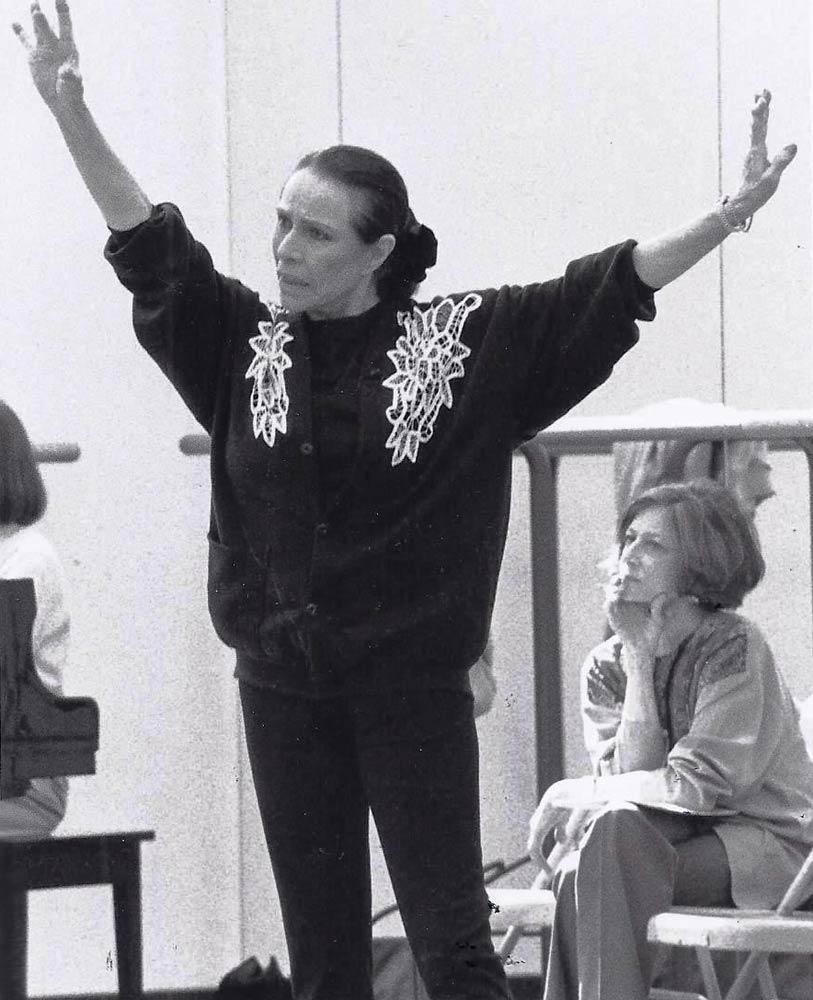

© Martha Swope. (Click image for larger version)

Did the Graham technique help you?

Well, I don’t know. Certainly not enough. I always had a weak back. I went to Pilates also. These were both Balanchine’s recommendations, which shows that he was concerned with his dancers. I left the company in 1961 and gave up dancing completely. Many years later when I’d gotten into dance history, I thought that what I should have done was at least try one other company. Robert Joffrey and Todd Bolender seemed to be interested in me, and people told me I was the kind of dancer Lucia [Chase] would have loved. But for me, Balanchine was the only thing. That’s silly, I know; there are lots of kinds of dance, and even lots of kinds of ballet. I might have been more successful in another repertory.

What fascinated you about Balanchine?

His choreography! And I didn’t really know anything else, except Sleeping Beauty, which I adored. I remember turning my nose up at Massine – he told stories and didn’t have all those wonderful steps. Of course now we wish we had more of those Massine ballets.

You were at NYCB during an extraordinary time. Diana Adams was in the company, as were Allegra Kent, Maria Tallchief, and Patricia Wilde. What was the atmosphere like? Did it feel like a golden age?

Balanchine was a god. Everybody says that, but it’s absolutely true. Most people who were there just worshiped him. I knew Stravinsky was around, and I saw some Agon rehearsals. It was obvious that Agon was an extraordinary event. Balanchine was around all the time; it was nothing special to see him in the hall. But I will tell you, there were lots of empty seats at City Center. We had Sunday evening performances, and from the stage you’d see rows and rows of empty seats. Balanchine said the same thing about Diaghilev’s company: there were full houses on glamorous opening nights, but often many empty seats after that. I was always a little embarrassed to say I was with NYCB, because the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and Ballet Theatre seemed like much more important companies. But I felt I was a pioneer, bringing Balanchine to the great public.

In a way, that adulation toward Balanchine in the company seems so unhealthy, at least on a personal level. Do you think he abused that power?

He knew he was the heart and soul of the company. I don’t know whether it was due to overweening pride or a quiet confidence in his abilities. In his youth he was also apparently quite personable with the young ladies. So perhaps he was used to being at the center of attention and just accepted it. But it was one of the big negatives. Because if you’re an adult you don’t like to have your life controlled by another person. So on the one hand I believed in his art to the utmost, but on a personal level I resented the situation.

Did you dance any featured roles?

I was a second movement demi-soloist in Symphony in C, and I did the Russian Dance corps in Serenade. 4 T’s [The Four Temperaments] and Serenade were my favorite ballets to dance. In 4T’s you could be a little bit geeky and not too classical, and Serenade just had such sweeping movement.

© Costas. (Click image for larger version)

In one way or another, your whole career has been devoted to Balanchine. What has sustained you?

At one point I tried to not specialize in Balanchine. In fact one of the reasons for writing No Fixed Points was to prove to the world that I could do something other than write about Balanchine. But it didn’t work too well! The entrance of the Balanchine Foundation into my life took care of that. There’s no doubt that you can see his ballets again and again and see something new in them each time. And the memory of him is very vivid – the memory of feeling that way, of believing in him so strongly.

Are you still learning new things about Balanchine through the Video Archives project you’ve developed for the Balanchine Foundation?

Each time I watch these coaching videos [in which steps are taken apart and analyzed in a studio setting] I’m astounded by all the things that I had never noticed before in his choreography. They are so eye-opening. Take the second aria in Stravinsky Violin Concerto–we did a taping earlier this winter coached by the roles’ originators, Peter Martins and Kay Mazzo. I always thought theirs was the “easy” pas de deux, and I was astounded to find out how difficult it is. At a certain moment, which the dancers practiced several times, the man and the woman link arms, the woman assumes attitude front on pointe and the man promenades her holding only her calf while she switches arms overhead. He then takes one of her hands and then the other as he swivels her to a low arabesque facing in the opposite direction from where she started. My lord! It seems as though she’s been on pointe with hardly any support for hours.

After you left the company, you went to college to study art history. Did that feel like your true calling?

My mother always talked about education, and when I wasn’t happy in the ballet I thought maybe she had been right all along. So I was very excited to go to college. I went to Columbia School of General Studies. My mother had majored in art history. I had planned to major in Greek; I was very intrigued by it, but it required you to do homework every night and one of the liberating things about college was that you could go for months without assignments. I greatly enjoyed art history, which turned out to have practical benefits as well.

How did you get into publishing?

In my first job out of college I was involved with the editorial side of an art encyclopedia. It was right up my alley because of my art degree and because we could be excused from the office to go to the Frick or the Met or wherever we needed to go for research. I didn’t intentionally choose publishing but I knew Praeger Publishers had a line of art books, so I interviewed there and was hired.

© Praeger Publishers. Image from Amazon sale page

And how did you get involved in editing Lincoln Kirstein’s Movement and Metaphor?

Mr. Praeger was very personable and he knew I had a dance background, and he said, why don’t you try to sign up a dance book? I was very much a junior editor at that time, so I phoned my friend Alex Schierman, who was Kirstein’s long-time assistant and whom I’d known since ballet school and I said, help! Can Lincoln recommend an author or a topic or anything? And she got back to me and said, “actually, he’s written a book of his own and wants to get it published.” So that was nothing short of sheer luck.

Did you already know him?

Not at all and he certainly didn’t remember me from NYCB. We started a brand new relationship. He was pleased that I had been a dancer. His book Movement and Metaphor is what turned me on to dance history. Before that I had always thought dance history was just a bunch of old Russians writing their memoirs. Editing that book really changed my life. And Lincoln also revealed himself to be a very kind and compassionate person, completely unlike his exterior and completely unlike his reputation. I thought he was a sweetheart, but at the same time I think he was having some sort of nervous breakdown. It was rough.

Did you experience his mood swings?

I remember his coming into the office one day and his mouth was drooping and he looked absolutely gray, and he walked down the hall, zigzagging from one wall to the other. I didn’t know that he was what today I think we would call bipolar. (That term didn’t exist then and neither did some of the medications now used to deal with the condition.) I would see Eddie Bigelow every so often and he filled me in. He said, “he’s an absolute genius, but he goes off the rails.”

What happened next?

I left my job because I found the office too confining. I wanted to be a free-lance editor. And I decided I wanted to live in Europe. By then I was married, but, so be it, I wanted to live in Europe anyway. I had studied quite a bit of German and I thought that if I went to Germany for a while I would crack the language once and for all. But what I really wanted was to live in Paris. After two months in the Bavarian countryside I moved to Paris but soon realized that I didn’t know how to make a life there. I had brought some editing projects from New York so I was sitting in my rented apartment editing in English all day and sightseeing like crazy. I loved the city but it was terribly lonely. After four months in Paris I came back to NY. Then I met Selma Jeanne Cohen; she was my second big influence as far as dance history goes. I applied to her dance history course at the University of Chicago. That’s what got me started. I admired her very much and I became interested in the idea of doing my own research, not just working on other people’s manuscripts.

© The Dial Press. Image from Alibris sale page

Is this what led to your writing the compendium, Repertory in Review, which covers forty years of New York City Ballet history?

Just before I went to Germany, the literary agent, Robert Cornfield, asked me – out of the blue – how would I like to write a book on the New York City Ballet? At the time I said, “oh no, I can’t, I’m going to Europe.” Amazingly enough when I came back six months later Bob still hadn’t found anyone to write it, so I took a deep breath and decided to try. But I didn’t do it full-time because I was scared to death. Writing had never been one of my ambitions.

How long did you work on it?

Five years. The great thing about Repertory in Review was interviewing all those people that I had once known and discovering a whole other side of them. It seems to me that when you dance with people all you talk about or think about is being onstage. That, and the state of your muscles. You have no idea about the rest of their lives. Over the course of writing that book I interviewed many people and I was just delighted and amazed. I realized I was comfortable in this world.

What was it like interviewing Balanchine?

I asked him about every ballet he had choreographed for NYCB and its predecessor companies. He gave me a great interview on Agon and a great interview on Nutcracker. We talked about Apollo, about Prodigal, about Ivesiana – about everything. He was quite engaging and he took me seriously enough to answer my questions. Because I had been a dancer he knew I sort of knew what I was talking about.

© Nancy Reynolds. (Click image for larger version)

You also put together Choreography by George Balanchine: A Catalogue of Works. Where did you go from there?

I felt the need to broaden my knowledge. I wanted to be a critic, which I never really achieved.

Why do you say that?

I’ve written very little dance criticism as such. I think I got side-tracked with writing books. I also taught at Brooklyn College. Yale asked me to teach a course, but I didn’t think I was any good at teaching, so I turned them down. By then I was into the writing groove.

Would you have liked to do more criticism?

Well, I thought I would. In New York, as writers critics are the kings and queens. Historians seem less important. On college campuses the situation is the opposite, especially if you’ve written a text used in class. But one of the reasons I didn’t pursue criticism is that I’m not a fast writer.

How many people were involved in researching Choreography by George Balanchine?

We had researchers all over the place. We had someone gathering clippings in Germany from the period just after Balanchine and Danilova left Russia; we had people in France, England, Australia and here. I could say, “I’d like to see a review of such and such a performance,” and they would find it. It was very well funded.

© Yale University Press.

How did No Fixed Points come about?

When I was at Praeger, they had a series called World of Art. The books were a little larger than pocket sized, and I got the idea of writing a book like that on twentieth-century dance. My agent, Bob Cornfield, sold the idea to Viking, but unfortunately as the years went by the manuscript got longer and longer, far exceeding the World of Art format. After 17 years I wasn’t nearly finished.

You had a collaborator on that book, Malcolm McCormick. When did he come on board and how did that work?

As No Fixed Points dragged on and on I began to think I was never going to get to the end, so I decided I needed a co-author. Malcolm was a costume designer and a former dancer and he did some teaching and wrote about costume design. I knew him from Selma Jeanne Cohen’s International Encyclopedia of Dance. I was the editor in charge of the art subjects, and when I got to the history of costume I was having difficulty finding an author. A friend suggested Malcolm as someone who had practical experience in the field and who could write the survey article. With No Fixed Points we decided which of the remaining chapters we would draft and then edited each other.

© Nancy Reynolds. (Click image for larger version)

How long did it take in the end?

I would say from first to last about 23 years.

And the International Encyclopedia of Dance?

Twenty-six years or something like that. [laughs]

When did you come up for the idea for the George Balanchine Video Archives?

It was just one of those things. I remember when it happened. I was sitting in Moscow watching Bourmeister’s Swan Lake at the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko musical theater, and it just came to me: wouldn’t it be interesting to see process? What would we give to have seen Mozart coaching Don Giovanni? In his will my father left some money to be put into a project of my choice. I was a friend of Barbara Horgan, so I knew of The Balanchine Foundation. My idea seemed to fit with what they were doing at the time, which was a video series on Balanchine teaching, The Balanchine Essays. I remember I was at a conference in England, and Alicia Markova said she remembered the variation from the Song of the Nightingale. Then at a lecture Freddie [Franklin] said something about remembering large parts of Baiser de la Fée.

How did the video sessions begin?

The first person I went to was Alicia Markova. She didn’t know me so I was astounded that she said yes. Then we had a party to announce my gift. Maria Tallchief was there, and she said that documenting and preserving Balanchine was the most important thing anyone could do. And Arlene Croce wrote something along those lines as well. So I thought, do I dare ask Maria Tallchief to participate? It took me a long time to get up the nerve. I began to think of others. I remember writing to Todd Bolender. Then I decided the first Mozartiana [of 1933] was an important ballet, so I started interviewing people about that. I interviewed Marie-Jeanne and others. It was a staple of the Ballet Russe [de Monte Carlo] for at least two years, so I got in touch with two former Ballet Russe people I already knew, Bobby Lindgren and Sonja Tyven. Then Freddie got interested in working with Julie Kent and Nikolaj Hübbe on the two pas de deux. Coaches have their choice of repertory and dancers. Melissa Hayden chose to coach Stars and Stripes and Donizetti Variations. She said something really interesting about Donizetti: “I don’t think it’s received the attention it deserves, because the music is so light, but let’s try doing it to Black Swan. And they did, and it made the choreography seem much more important and grand. We have it on video, with Gillian Murphy and Peter Boal.

© Brian Rushton. (Click image for larger version)

How many coaching sessions do you film per year?

Two or three. Sometimes the teaching is done from scratch, but if it’s a complicated ballet we try to get a dancer who already knows the role because it’s impossible for them to learn it during the session. So we look for a dancer who knows the part and whom the coach wants to work with.

And how long are the sessions?

We try to do two hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon, and then an interview. They usually last two days; once we did three, and that proved to be too long. Maria [Tallchief] chose Jennie Somogyi to do some variations, and by the third day they were both absolutely exhausted.

How many people do you have on staff at the video archive?

It’s me, and I have a technical advisor. We have a couple of post-production houses that we use. About two years ago we asked Nichol Hlinka to join us, and she’s a great addition. We had an office for a while but it seemed like a waste of money.

Do you ever get dancers who are resistant to the coaches when they teach them a different approach to a role they already know?

No, because I say to them beforehand, “for these sessions, please do what the coach says, even if you know the choreography and interpretation are different now, because this is for the record.” What we’re trying to do is capture what the coach originally danced and how he/she danced it and what Balanchine said or demonstrated at the time he was creating it. There are many versions of these ballets; we are not supplying the version.

And what about the Archive of Lost Choreography? Is that an ongoing process?

Well, once video was invented nothing is really “lost” any more. So you need to find ballets that not only are no longer danced but that have never been recorded. I got Markova to stage the variation from Chant du Rossignol and Freddie to stage excerpts from Raymonda, Baiser de la Fée and Mozartiana, but he said he didn’t remember any others. Todd Bolender did Renard and Stanley Zompakos did the Gigue from Mozartiana. But I don’t know anyone else who could do it.

© Brian Rushton. (Click image for larger version)

Do you know who uses the videos?

We have a list of the participating libraries on the website. I think we’re up to 76. Only educational institutions, libraries, and other non-profits can buy the videos, not individuals.

Why not individuals?

I think once you get into commercial distribution your relationship to the marketing changes.

Is it available on streaming video?

There’s an outfit called Alexander Street Press that does streaming video on the Internet by institutional subscription.

There is an amazing level of detail and nuance that is provided by the coaches in these sessions. Are you afraid that without something like the Video Archive these nuances, and the intention behind them, might be lost?

I think we know that things are being lost. It seems to me that, apart from the steps themselves, any nuances Balanchine imparted to his choreography are worth preserving.

© Marina Harss.

Are there sessions in which the stagers disagree about details?

Yes… (laughs). Well, we haven’t had that in a while. I think the only time it got a little bit heated was when we had three people. We had Vida Brown, Maria [Tallchief], and Freddie [Franklin], and there were places where there was disagreement. At one point Maria pulled out some notes from 1940.

Has anything you’ve seen in these sessions surprised you or changed the way you thought about a particular piece?

It’s sharpened the notion that Balanchine’s choreography evolved over time and that there’s such a thing as a forties style and a fifties style, etc. To some extent he evolved with the times, with different dancers, and used different accents. And I’m amazed by the amount of detail I never noticed. I can’t believe I watched these ballets for years and didn’t notice all kinds of things. I find it particularly interesting to watch the partnering, the effects of which are often hidden on stage. We recently did a tape of Suzanne Farrell coaching Meditation. The choreography is supposed to look seamless in performance, but when you see it analyzed, with the dancers in the studio in practice clothes, you marvel at how unexpectedly ingenious and complicated the partnering is.

© Martha Swope. (Click image for larger version)

In a way, would you say that the Video Archive is the greatest accomplishment of your career?

[Long pause.] If I were to be remembered, I would like to be remembered as a writer. Writing is the most challenging thing I’ve ever done – except for dancing. But if I’m remembered at all, I think it will be for the archives.Who do you think are the interesting choreographers of our time?

Probably Wheeldon, Ratmansky, and Morris – not very original choices! James Kudelka and Alonzo King have done interesting things in the past although I’m not familiar with their recent work. But I don’t think we know enough about what’s around us. Kent Stowell did a gorgeous Romeo and Juliet – to Tchaikovsky, by the way – and a wonderful Nutcracker with designs by Maurice Sendak. (Full disclosure: he’s a personal friend). I think Trey McIntyre is very talented. I’d like to see more work by Aszure Barton, and I’m curious about Pam Tanowitz. Then there’s someone called Paul Vasterling in Tennessee who I hear is good. But these last named are not widely recognized because the big companies mainly assign choreography to their own or turn to well-known outsiders. They should sit and watch lots and lots of videotapes. I’ll bet there are good people working out there who most of us don’t get a chance to know about.

[…] Here is a link to the interview. […]

Wonderful interview. Captures Nancy’s charming modesty? I learned a lot.

As usual, Marina is spot on in the ability to pose questions that elicit the responses which are so informative. She also reveals the Reynolds generosity of spirit.

Thank you both! Nancy is such a remarkable woman.

When former dancers die i get so upset thinking oh my gosh were they interviewed? … was something of their unique reality and domain given before they died? Nancy Reynolds and wonderful others have given great invaluable labor to preserve painstakingly what should be preserved. sometimes i will read a great dancer write they were profoundly upset seeing a certain balanchine ballet performed today because the entire essence of the ballet was lost. the entire, extremely brilliant and particular way the steps were supposed to be performed completely missing. the magic no longer visible. this is always so painful to hear. reynolds’ work is so crucial. her mentality so correct that the true essence of what makes a certain balanchine ballet have its original “singingness” is a vital and wonderful aim with a very high purpose.

i know balanchine said his works will change and wont be his anymore. and farrell often talks about his choreography and ballets being a live, evolving , vibrant thing ( though she too is painstakingly trying to wholistically preserve and remember as precisely as possible balanchine’s works).

but if a ballet’s modern manifestation is less good or greatly less good or even dull compared to the original work and the ballet dancers less interesting and more uniform (as also i have read) then i feel very bewildered and think how can we change this. how can we correct this.

anyway i have never gotten to see any of these things for myself so i dont know the reality of the ballets or performances of them directly. ever. i wish i could have experienced the beauty for my own self. i wish i could have been in those first empty rows of so long ago that reynolds spoke about.

i remember gelsey kirkland in her famous book “dancing on my grave” write that she was crying seeing allegra kent dancing one time because it was so profoundly beautiful…

witnessing something in moments in time is such an incredible and extraordinary thing… such a great gift… a great, temporal gift but when these great “gifts” can be captured in film for others to witness what an incredible gift as well which can keep giving such great joy to others ongoingly in time…i am so profoundly grateful for filmed performances… words couldnt express it… film might be inferior to live performance but filmed performance is dramatically superior to zero and eternally uncaptured performance…

an ending note: nancy reynolds was so beautiful and elegant in that 1977 photo with balanchine and also her photos of she as a dancer were so beautiful (despite her saying she wasnt that good. but it was hard for everyone. diana adams said in the gem of a book “remembering balanchine” i think it was that she oftentimes felt strained (my paraphrase) in dancing balanchine and trying to live up to expectations )…

interviewer marina harss was so terrific… i loved this rich, substantial piece…it was so very satisfying…i loved hearing about the wonderful allegra kent… if the great alicia alonso is on tape what a great thing… (a final aside:alonso’s white swan was one of the most beautiful that i have ever seen…)… i bless the internet for articles such as these.. Brenda Du Faur

***When former dancers die i get so upset thinking.oh my gosh wete they interviewed … was something of their unuque reality and domain given…Nancy Reynolds and wonderful others have given great invaluable labor to preserve painstakingly should be preserved. sometimes i will read a great dancer write they were profoundly upset seeing a certain balanchine ballet performed tiday because the entire essence of tge ballet was list. the entire extremely brilliant and particular way the steps were supposed to be performed was entirely missing. the magic completely gone. this is always so painful to hear. reynolds’ work is so crucial her mentality so cirrect that the true essence ofxwhat nakes a certain

sorry that last paragraph of my comment got accidentally repeated in my pasting of it