© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

Paul Taylor Dance Company

Gala: Junction, 3 Epitaphs, Perpetual Dawn, Offenbach Overtures

New York, David H. Koch Theater

5 March 2013

www.ptdc.org

davidhkochtheater.com

At a Gala, Paul Taylor Works, New and Old

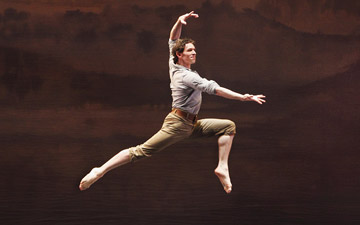

The Paul Taylor Dance Company is back at Lincoln Center, looking quite at home on the beautiful wide stage at the Koch Theater. You’d never know it was only a year since their move from City Center. With their buoyant leaps, supple backs and radiant faces, these super-athletic dancers easily fill the space. One marvels at their energy. Taylor’s choreography is fast, full-bodied, aerobic: it seems to engage every muscle in the body. The sixteen dancers perform several pieces per night and yet they appear no less vigorous and cheerful during their final bows than at the start. How do they manage it? One wonders what they look like in the morning.

© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

Opening night (March 5) was a gala performance; one might have expected Esplanade, or Arden Court, but that’s just not Taylor’s style. For a choreographer who has been criticized for being too popular in his tastes, Taylor can be very odd indeed. Junction (1961), which opened the gala program, is one of his strangest works. It was his first foray into the classical music repertoire, a year before the joyous Aureole. As he often does to this day, he picked music that was almost too familiar: Bach’s cello suites. Last year, when the dance was revived, he told the writer Nancy Dalva that Junction had been “an experiment for me to sort of clarify my idea of what was musical in a dance, and I decided that I would try not just to go fast when the music went fast and slow when it went slow, but to complement and sometimes do the opposite.” But it’s not just that. The tone and look of the steps – awkward, vigorous arm flapping, exaggerated curves in the back and abdomen that make the dancers look like insects – is so far removed from internalized, rigorous esthetic of the cello pieces that the two hardly seem to inhabit the same world. Is he poking fun at the music? “Take that!” Taylor seems to be saying, “I can take these orderly, cerebral pieces and use them however I want.” The steps are awkward, violent, even, at times, ugly. They seem willfully to ignore the music. But the dance is filled with remarkable images and contrasts. A dancer (Amy Young) moves with furious speed and attack, swatting wildly as a group of dancers moves slowly, laboriously behind her. Is she in distress? Are they? While the stage teems with activity, a woman crouches for a long time on a man’s back; he kneels on all fours, forehead to the ground. When the woman finally stands, still balancing on the man’s back with her arms extended, the others fall forward around her, paying tribute. Men roll across the stage, sweeping one arm forward as if scooping something off the floor. A weird scuffle breaks out, bodies piled and torqued as in a game of Twister. A woman is carried about, folded up like a package, and passed from man to man. The movements are executed with an air of total seriousness. The dancers’ expressionless faces are in stark contrast with the bright, color-block costumes and the simple backdrop of red stripes, which, one later realizes, are actually ribbons (by Alex Katz). The more often one sees Junction, the weirder it seems.

© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

Then, after a performance of the brief 3 Epitaphs (1956) – a witty piece for five completely masked figures who lope around like indolent simians – came the novelty of the evening: Perpetual Dawn. It’s one of two new Taylor works this season. Dawn turns out to be a pretty, bucolic piece, set to various fragments from Johann David Heinichen’s rather nondescript Dresden Concerti. The most one can say about the music is that it is cheerful, and that it must have made lively background music for parties at the court of Prince Leopold, Heinichen’s patron. Taylor has responded with a pleasant, rather generic dance for a series of couples dressed in modified peasant costumes by Santo Loquasto. The mood is happy, with a slight note of nostalgia. Love is in the air. Young lovers leap like gazelles; women are joyfully cradled; smiles abound. The backdrop, a pastoral landscape (also by Loquasto) is tinted in pink light, then blue, then pink again (by James F. Ingalls). Girls recline in the fields in decorous repose. Michelle Fleet, finding herself alone, scampers around in search of a partner, as she does in Esplanade; then she runs away as yet another rapturous couple enters to dance an earthy duet filled with cartwheel lifts and swings. Two women engage in an emphatic mime sequence – straight out of Giselle – though it’s never clear what they’re trying to say. No matter: it’s just one of Taylor’s jokes. The scene ends, incongruously, with the two engaging in a few phrases of the Charleston. The most intriguing sequence is for two boys who tilt back in an exaggerated pose – it reminded me of the marching soldiers in Company B – arms bent upward, kicking the air. Then they creep off sideways on the tips of their toes. But once again, it’s not clear what the movements are meant to suggest. It’s a generous dance, with something for everyone to do, but not terribly focused, and certainly not one of Taylor’s most original.

© Tom Caravaglia. (Click image for larger version)

The surprise of the evening (for me) was the closer, Offenbach Overtures (1995). The last time I saw this dance, several years back, it struck me as forced and cartoonish. This time it won me over completely. Has it changed or have I? Set to appealing Offenbach polkas and waltzes and costumed (by Loquasto) in simplified versions of soldier uniforms (including mustaches) and chorine outfits straight out of Toulouse Lautrec (all red), the piece pokes fun at ballet, at puffed-up nineteenth-century European conventions, at operetta, at heterosexual coupling. Parisa Khobdeh, playing a tipsy, disheveled ballerina who keeps falling down, hair flopping indecorously, is simply hilarious. She stays in character throughout the dance, even when she is barely noticeable at the back of the stage. But the pièce de résistance is a duel between Michael Trusnovec and Sean Mahoney. After a very formal preparation (Trusnovec even waxes his whiskers), the two square off. But then, the switcheroo: it turns out that this duel is actually a dance-off. Each man shows off pompously for the other: pirouettes! double tours! They throw off every trick in the book, not always successfully (bien-sur). But gradually it becomes clear that what was once enmity has turned into mutual admiration, and admiration into love. (Meanwhile their seconds have become embroiled in a messy brawl.) The duelers blow kisses, each sneaking over to his rival’s side for a rapturous embrace, until finally they run off in each other’s arms.

© Paul B. Goode. (Click image for larger version)

If the dancers look more comfortable in this antic dance than they do in Perpetual Dawn it is because Offenbach knows exactly what it is meant to be. It’s also possible that Perpetual Dawn will become more interesting as the dancers settle into it over time. (Though nothing can fix the music.) There is still another première to look forward to, To Make Crops Grow, as well as a revival of Taylor’s hilarious Sacre du Printemps (the Rehearsal). It’s a packed season, twenty-one works in all, not all of them masterpieces, of course. But sometimes the weirdest pieces can be the most interesting.

You must be logged in to post a comment.