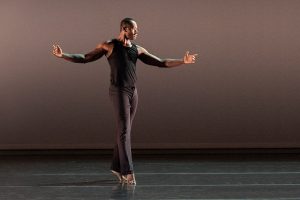

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

American Ballet Theatre

Symphony in C, The Moor’s Pavane, Symphony #9

Washington, Kennedy Center Opera House

9 April 2013

www.abt.org

www.kennedy-center.org

With two symphonies on its program along with a great selection of Baroque music, the American Ballet Theater’s triple bill, presented at the Kennedy Center Opera House during the company’s six-day visit in April, featured a symphonic offering to satisfy the most discerning music aficionados; and with choreographic masterpieces by George Balanchine and José Limón and a Washington D.C. premiere of Alexei Ratmansky’s new work, the ABT program was in every way a balletomane’s dream come true.

Balanchine’s Symphony in C is a thrilling visualization in movement of Georges Bizet’s first symphonic work, Symphony in C Major. The music, which the French composer wrote as his conservatory project when he was just 17 years old, abounds in bright energy and sunny charm and possesses an unmistakable operatic flair. Balanchine’s choreography, in turn, transforms Bizet’s melodic exuberance into a dazzle of intricate steps and fascinating patterns.

It was Igor Stravinsky who in 1947 introduced Balanchine to Bizet’s little-known score. At that time, the choreographer was a guest ballet master at the Paris Opera Ballet and contemplated a new work for the famed French troupe. Bizet’s inspiring melodies hit all the right notes with Balanchine, who staged and choreographed the entire ballet, nobly titled Le Palais de Cristal, in a mere two-week period. The original production was lavishly designed, with costumes of a special color for each of the ballet’s four movements (red, black, green, and white, representing rubies, black diamonds, emeralds, and pearls). A year later, Balanchine reworked the piece for Ballet Society (the precursor of New York City Ballet) with the costumes simplified to take on a black-and-white color palette (white satin tutus for the women and black plain costumes for the men), the choreography adapted and accelerated to better suit the NYCB dancers, and the title changed to honor the composition to which the ballet was set.

Balanchine’s Symphony in C is carried forward by the surge of music and movement – exquisite formations one after another spilling onto the stage to match the pattern and the flow of the music. Clarity and speed are not only of great importance here, they become the intrinsic essence of the dancing itself. The revised ballet has kept the hierarchical structure of Le Palais de Cristal: at the center of each movement is a principal couple, behind them two solo couples, and further to the backdrop the dancers of the corps de ballet. It’s a ballet about ballet, designed to showcase the exceptional talents of the ballerinas, their speedy footwork, and their precise timing and musicality. Whether they are the members of the corps or the principals, the women, who outnumber the men 40 to 12, shine and enchant as they preside over each section of the dance.

The real pleasure of watching ABT perform a Balanchine ballet is seeing how its dancers, with their striking individuality and unique virtuosity, give Balanchine aesthetics a new perspective. Despite a few uneven moments, the opening night cast had a bevy of standouts and the ensemble certainly got the spirit right, if not the details. Paloma Herrera led the first movement with supreme authority and firm control of her line and position. In Adagio, Hee Seo’s extensions and balances were superlative; she seemed to luxuriate in the music, beautifully stretching her body and complementing her every movement with elegance and lyricism. Daniil Simkin brought loads of bravura and youthful abandon to the third movement, Allegro Vivace. Sarah Lane and Jared Matthews, joined by the entire cast, perfectly matched the luminous rush of the music in the ballet’s ebullient, thrilling finale.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

José Limón’s The Moor’s Pavane, now nearly 65 years old, is an enduring classic of 20th-century modern dance. Set to a sonorous medley by the English Baroque composer Henry Purcell, this 20-minute piece danced by two couples captures the emotional core of Shakespeare’s Othello, depicting the convoluted and fateful relationships among four main characters – The Moor, His Friend, His Friend’s Wife, and The Moor’s Wife (Othello, Iago, Emilia, and Desdemona). Premiered in 1949 at the American Dance Festival, with Limón himself in the role of The Moor, the dance has captivated audiences with its taut drama and profound theatricality ever since.

The ballet is choreographed as a slow-motion pavane – a Renaissance court dance with ceremonial, elegant gestures and decorous bows and reverences. As a white silk handkerchief – which serves here as a visual metaphor for the human condition – changes hands among the personages, the tragic story of love and betrayal unfolds to its fateful end. It is powerful dance-theater, displaying with jarring intensity and precision the universal themes of Shakespeare’s monumental drama – desire, jealousy, obsession, and deceit.

The Moor’s Pavane is a terrific vehicle for the ABT dancers, and the opening night cast, with the superb Marcelo Gomes in the role of The Moor, reached the ballet’s magnificent heights in a compelling, heartrending performance. Cory Stearns gave an impressive portrayal of a manipulative and devious Iago, Stella Abrera was utterly convincing in the role of his scheming yet gullible wife, and the delicate and ethereal Julie Kent was solemn and vulnerable as The Moor’s Wife; but it was the breathtaking performance of Gomes in the title role that will stick in memory the most. His Moor was a towering presence from beginning to end: powerful in his bearing, violent in his rage, and poignant in his grief.

Ratmansky’s Symphony # 9, the final dance of the program, is full of surprises and unexpected twists, just like its music – Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 9 in E Flat Major, Op. 70, which feels more like a witty musical comedy than a serious symphonic work. “You have to have as much of a sense of humor to appreciate this music as Shostakovich had to have in order to write it,” Leonard Bernstein said about Shostakovich’s Ninth. Shostakovich himself referred to it as “a joyful little piece.” Joyful and extremely brave, I would add, considering the historical circumstances under which this symphony was written. Instead of the widely-expected symphonic epic – patriotic in character and majestic in scale – to commemorate the end of the Second World War, Shostakovich’s concise and playful composition seemed like a slap in the face to Soviet authorities – an apotheosis to Stalin it certainly wasn’t. Shortly after its premiere in Leningrad, in 1945, the symphony was banned for its “ideological weakness” and not performed until 1956.

Ratmansky was attracted by the symphony’s wide spectrum of contrasting emotions, which range from grotesque and heroic to melancholy and romantic. He was also drawn by the danceable nature of the music and its unpredictable and relentlessly bouncing tunes. In his new ballet, the choreographer refracted all these musical intricacies and surprises – melodic, rhythmic, harmonic – into a rich tapestry of visual images and shifting moods, some of them vividly evoking snapshots of post-war Soviet life with its cheerful May Day parades and painful WWII memories.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

As the music starts, a happy giddiness sets in. The first movement is merry, bright and dynamic, sending the dancers – a soloist couple (Simone Messmer and Craig Salstein), and four couples of the ensemble into an ardent, whirling dance. Echoing Shostakovich’s breezy string arpeggios and jaunty, cartoonish-like woodwind solos, the steps are lively and sharp and the rapidly-changing groupings are flecked with humor and imbued with youthful spirit.

The second movement brings a somber, tranquil atmosphere – quite a contrast to the ballet’s kaleidoscopic opening. The music is rather melancholy, “a quiet, sweet little waltz” opening with a haunting, lyrical clarinet solo. It invites a slow, sinuous pas de deux, exquisitely danced on opening night by Roberto Bolle and Veronika Part. They lose themselves in a delicious flood of highly imaginative movements, sprinkled with a dash of mime. Ratmansky’s choreography here is bracingly fresh and offers an ample dose of achingly beautiful movements, at once intriguing and intimate.

The ballet culminates in wild dance frenzy by the entire ensemble, with a male soloist (Jared Matthews) looking like a spinning vortex of energy. Desperately trying to set himself free from this tornado-like whirl, he jumps as if reaching for the sky, his fingers splayed like rays of light as the stage goes dark.

Symphony # 9 is drenched in enigma. The ballet’s three movements are veiled in such potent mystery that one hesitates between looking for clues or just watching them unfurl. Some of its mysteries might be uncovered in two brand 1-new Shostakovich-inspired ballets set to the composer’s Symphony #1 and Chamber Symphony for Strings, which together with Symphony # 9 will form a full-evening trilogy when premiered by ABT during the company’s spring season at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House.

You must be logged in to post a comment.