© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

English National Ballet

Ecstasy and Death: Le jeune homme et la mort, Petite Mort, Etudes

London, Coliseum

18 April 2013

Gallery of 30 pictures by Dave Morgan

www.ballet.org.uk

The title of Tamara Rojo’s first triple bill for English National Ballet, Ecstasy and Death, could apply to numerous ballets, including those appearing simultaneously in London: the National Ballet of Canada’s Romeo and Juliet and the Royal Ballet’s Mayerling. Sex prefigures death: no happy endings there, though sometimes, as in Swan Lake and La Bayadère, there’s the chance of an apotheosis.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

There is one in Le Jeune homme et la Mort, the 1946 ballet Roland Petit gave ENB shortly before his death in 2011. The young man of the title experiences sadistic sex, suicide and transfiguration – of which more later. Le Jeune homme is preceded in the programme by Jiri Kylian’s Petite Mort, named after the ‘little death’ of orgasm. The 1991 work, new to ENB, used to be in Rambert’s repertoire: it opened the renovated Sadler’s Wells Theatre in 1998. Guaranteed to please audiences who appreciate honed, semi-naked bodies, Petite Mort supplies supple simulated sex to the slow movements of two Mozart concertos.

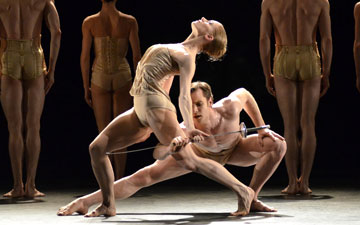

It opens with six men in flesh-coloured corselets playing with fencing foils as somewhat unpredictable partners. A swoosh of silk reveals six slender, steely women ready to replace the weapons. The women can support the men’s bodies as well as be lifted aloft by them, legs outsplayed. Power is shared, though the women are blatantly manipulated into submissive positions. ENB’s female dancers, feet arched on three-quarter pointe, make Kylian’s angular choreography look very balletic. Some ingenious games with crinolines on wheels lighten the sultry atmosphere, while Mozart’s sublime music sails on regardless.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

When Le Jeune homme et la Mort was new, the use of Bach’s Passacaglia in C minor for a work celebrating squalor and suicide was as startling as the cigarettes smoked on stage and the modern watch on the man’s bare arm. His paint-stained dungarees were a forerunner of jeans, the sweat of his exertions visible. Jean Cocteau, whose idea the ballet was, wanted the impoverished artist’s atelier to be ‘splendidly sordid’. (The drawings on the peeling plaster walls were by Cocteau himself). All the battered furniture was to be put to use in the action.

And what action! Nicolas Le Riche, étoile of the Paris Opera Ballet, erupts from the artist’s unmade bed in a frenzy of impatience and anxiety. This is a dancer accustomed to occupying a huge stage, a 41-year-old man who still hurls himself off tables as though flying. I saw him in the role at the Palais Garnier in 2000, and his magnetic energy seems undiminished. His jeune homme is not world-weary with existential angst but wired for a fix: he’s a sex and/or drug addict. Rojo is the woman (or hallucination) he has been waiting for, demonically beautiful in sulphur yellow.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

The role is often taken by a tall woman (though tiny Zizi Jeanmaire danced it with Rudolf Nureyev). Small Rojo, who has been longing for the role, succeeds in dominating tall Le Riche with unholy glee. Her black gloves are talons, her foot in a pointe shoe like a scorpion’s tail brushing the man’s groin. She blows cigarette smoke in his face and offers a blow job with contempt. On opening night Rojo was over the top, too triumphant too soon, instead of being an implacable force. Her seductive taunting became repetitive, so that the climax of his hanging seemed yet another sex game gone wrong rather than his tormented desire for quietude.

I relish the melodramatic apotheosis, in which he and we realise the woman was Death all along. She leads the man she has claimed over the roofs of Paris – the Paris of 1946, with the Eiffel Tower advertising Citroen cars in large letters. Petit’s ambitious young company, le Ballet des Champs-Elysées, couldn’t afford the transformation Cocteau had envisaged, so the designer, Georges Wakhevitch, appropriated a set he had prepared for a recently completed film: Martin Roumagnac (1946) with Marlene Dietrich and Jean Gabin. The set arrived at the last minute, just as the decision was taken to swap jazz music for Bach’s Passacaglia – a choice as seemingly arbitrary as those made by John Cage and Merce Cunningham.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Rojo has declared that her ambition as artistic director of ENB is to make audiences hold their breath. I certainly did during Le Jeune Homme et la Mort, watching Le Riche overturn chairs and upend himself on tables. And I did during the closing ballet, Études, willing the company to get through its technical demands without fumbling. Harald Lander’s 1948 Études, made for the Royal Danish Ballet, has been in Festival Ballet’s/ENB’s repertoire since the 1950s, danced by a succession of starry guests and variable home-grown corps. When it used to be performed at the Festival Hall, burly catchers had to stand in what passed for wings in order to field fast-moving bodies before they piled into each other. The Coliseum has plenty of space, though speedy criss-crossing sequences can still be hair-raising.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Tricky for today’s dancers are Lander’s expectations in the 1940s of the technique required of Danish dancers. To perform August Bournonville’s ballets they needed fleet footwork, petite batterie and precise pirouettes, as well as bounding jumps. Études starts with drilled classwork at the barre and progresses through the small beaten steps, often left out of modern training, to the flamboyant ones that impress audiences. En route, there’s a Romantic interlude to demonstrate how academic orthodoxy can be nuanced for ballets like La Sylphide and Giselle. Erina Takahashi was charming with Esteban Berlanga as her assiduous partner, but the section does go on.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

So does the ballet at 40 minutes, unless you’re enjoying the technical challenges. Vadim Muntagirov and James Forbat overcame them all. Though both prefer to turn to the left, they can switch without problems when joined by right-turning female corps members. Muntagirov, not a show-off by nature, accomplished every feat with aplomb, matching Forbat in wrapping his lanky legs around a formidable sequence of beats. Muntagirov withdrew from subsequent performances because of injury, but there was no sign of any impairment on the opening night. Congratulations must go to Rojo and her team of coaches for bringing the company up to such a high standard.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

You must be logged in to post a comment.