© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

American Ballet Theatre

A Month in the Country, Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes, Symphony in C

New York, Metropolitan Opera House

21 May and 22 May (mat) 2013

www.abt.org

Tremblement d’Amour

Has there ever been a more sensitive, sympathetic chronicler of that inner flutter brought on by the onset of love than Frederick Ashton? It seems unlikely, on the evidence of two back-to-back performances of his late work A Month in the Country at American Ballet Theatre (a company première). In forty-five minutes and with the assistance of Chopin (and, indirectly, of Mozart), Ashton has taken the heart of the Turgenev play and turned it into a series of tender miniatures. With great skill, wit, and love, he sews them together (with ribbons) into a portrait of a sentimental married woman experiencing pangs of longing for a young man, but also of her comfortable little world and the emotions that turn it topsy turvy. Russia, by way of the Cotswolds.

The curtain opens on a scene that tells the audience everything it needs to know about the “family unit” in question: A young boy does his homework at a desk, and an elderly gentleman (Yslaev, head of this respectable household) reads the paper, sprawled out on a chair. A young girl (Vera) practices the piano in an adjoining room, and Natalia Petrovna, our heroine (danced on the 21st by the fine-boned and nervously girlish Julie Kent) engages in flirtatious repartée with a harmless admirer on a settee. A stiff-backed footman picks up a glass carelessly left on the floor. The walls are covered in (probably second-rate) paintings, floor to ceiling, in the Russian manner; the French windows, open to the breeze, reveal a little bridge, and beyond it, a late-summer sky and some melancholy firs. (The descriptive, but not heavy-handed designs are by Julia Trevelyan Oman, as are the layered, laced, and beribboned costumes, which billow fetchingly whenever the dancers turn or jump.) Ashton revels in the slight ridiculousness of the scene. Petrovna, a woman past her prime, is a ham; the admirer, sitting at her feet, will get nowhere; the boy quickly tires of his studies; the husband hasn’t a clue. Chopin’s variations on the aria “La ci darem la mano” from Mozart’s Don Giovanni play in the background. The musical choice could not be more suited to the scene: it is light and easy enough to be convincing as a piece a young girl might actually be practicing on the piano.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

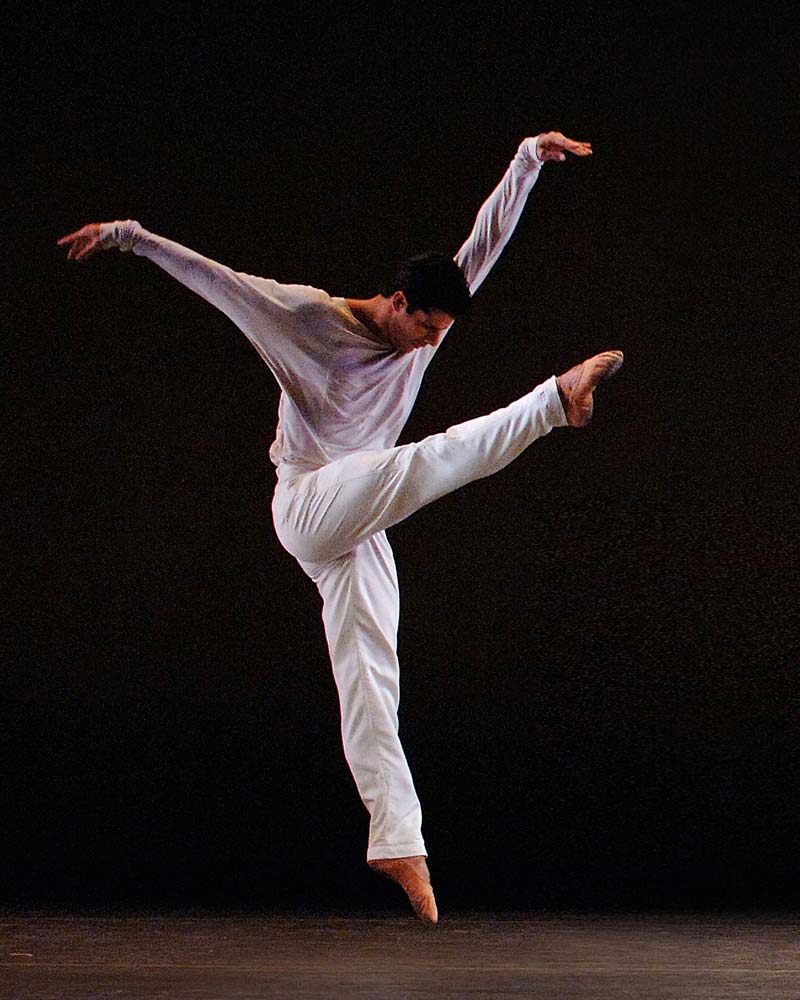

Then comes a masterful little melee: everyone joins in the search for Master’s keys – there is much quick bourréeing across the floor and bumping into each other, crawling through each others’ legs and lifting people out of the way. And then another set piece in which the boy (Kolia) plays with a ball while performing a series of wham-bam stunts (double tours, split jumps, a manège of jetés in attitude, pirouettes à la seconde performed while passing the ball under his leg). Ashton’s pacing is perfect; one action flows into the next, and time just melts away. By the end of Kolia’s playful solo (and of Chopin’s Theme and Variations) the audience is practically out of breath, and precisely at this moment Ashton creates a little pause for reflection. A slight breeze moves the curtains, and a handsome young man appears in the French window, carrying a kite. The temperature in the room changes. It’s the boy’s tutor, Beliaev, and all eyes (except the husband’s) are on him. Kolia loves and admires him; Vera adores him as only a young girl experiencing her first crush can. The admirer (Rakitin) watches him with guarded distaste. And Natalia Petrovna, well, she has fallen in love. From that moment on, everything she does is for him.

What makes Beliaev so captivating? Nothing, really: In the end, one realizes that it’s not about who he is, but what he represents. He embodies the almost unconscious sensuality of youth, the promise of young love. In a way, he’s a slightly older version of the boy in Death in Venice. Ashton doesn’t try to explain too much; he merely shows Beliaev to us for what he is, through loving eyes. He gives him simple, limpid, almost innocent steps. He’s playful, a little gauche, occasionally ardent. He’s good to the boy and kind to Vera, not leading her on, exactly, but enticing her with his tender concern. And he’s jolly, too, joining in a funny little parlor dance with the whole family. In one of his two solos he looks slightly bored, distractedly sketching out Russian steps, hands behind his back, small kicks and changes of direction in arabesque, the better to show off his youthful poise. (Petrovna watches adoringly.) Just before that, he engages in a flirty dance with the maid and she plops strawberries into his mouth. But he’s fascinated by Petrovna. He caresses her lace scarf adoringly, like Cherubino in Marriage of Figaro. He’s in love with the idea of her, the promise of passion with an older woman.

All of this leads of course to the inevitable dénouement, a tumultuous pas de deux for Petrovna and Beliaev, in which she becomes almost unhinged with happiness. It’s filled with marvelous detail: rapturous lifts with legs fluttering, entwined hands, an embrace in which her arm wraps around her neck (the yoke of love), tiny tiny bourré steps that zigzag across the floor. Ashton pushes her rapture right to the edge of ridiculousness, even, at times, stepping over the line. But he is right to do so; humans are slightly ridiculous when they think they’re in love. The emotion is all the more real for being so absurdly excessive. Of course, everything goes downhill from there: Vera spies the tryst and makes a public accusation, forcing Petrovna’s hand. Young Beliaev leaves the household, along with the long-suffering admirer. One can’t help but think that Ashton’s sympathies lie with this character, a man of the world who knows a thing or two about thwarted love. Ashton give him the famous “Fred step” as he and Petrovna walk out into the garden, arm in arm: arabesque, developpé, pas de bourré, pas de chat. (Ashton picked it up from Pavlova, and liked to drop it into every ballet, like a talisman.) Its gentle rocking motion encapsulates that familiar, everyday feeling that one associates with Ashton’s ballets.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

In the final moments, Ashton throws in a heart-rending touch: as Petrovna cries, alone, Beliaev returns, kneels down, kisses the ribbons of her dressing gown, and departs once more, this time forever. It’s completely over-the-top and just perfect. Right on cue, the heart catches in the throat. The casting on May 21 worked very well and the matinée of the 22nd was, in a way, just as good. Julie Kent was histrionic and imperious and slightly over-ripe, shaking her shoulders and twisting her wrists with like a capricious child. (Hee Seo, in her début on the 22nd was more rapturous, with gorgeous lines, but too young to capture the desperate, foolish side of Petrovna.) Roberto Bolle, his matinée idol looks only slightly marred by long sideburns, was less convincing; looking rather stiff, he seemed afraid to color the steps or give any interpretation at all. (David Hallberg, on the 22nd was far more impetuous, more hotheaded, and more supple.) Gemma Bond, a young dancer trained at the Royal Ballet and an excellent actress, threw herself into the role of the young girl, floating high on the wings of hope one moment, crushed and humiliated the next, then hysterical and angry as only a teenager can be. (Sarah Lane was more child-like and less funny but just as touching in her own way.) In the role of Kolia, Daniil Simkin (21st) danced with his usual crisp, clear, perfectly controlled virtuosity, but lacked charm. Aaron Scott’s footwork was less pristine, but more convincingly boyish. And I’ve never seen Stella Abrera look as animated and quick on her feet as she did in the role of Katia, the maid, on the 21st. Simone Messmer was more flirtatious, sharper.

The program opened with Mark Morris’ Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes, a suite set to piano pieces by Virgil Thomson (played onstage). This chamber ballet, with its witty off-kilter positions and sparse, asymmetrical patterns, is more suited to a smaller theatre. But as the piano pieces grow increasingly lyrical, and the dances more expansive and relaxed, leading to a kind of quietly elegiac ending, the dimensions of the theater cease to matter. One is pulled in by the casual beauty and musical intelligence of the world onstage, and Morris’s loving quotation of classroom steps. Isabella Boylston and Marcelo Gomes stood out in particular (on May 21) for the lushness and freedom with which they infused the choreography. Joseph Gorak danced an outrageously well-articulated solo on the 22nd; he was also a marvelous Lensky last week. Give this young man more roles, please.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

Then, after Month, the evening closed with Balanchine’s Symphony in C, a striking reminder of the chasm that separates these two choreographers. If Ashton’s world is a nineteenth century cameo, all curls and eyelashes, Balanchine’s is a shimmering diamond, incomparable and slightly inhuman. A resplendent universe of legs and arms, all air and clarity and timeless perfection. In place of Ashton’s frou-frou, body-against body partnering, we get hands encircling wrists with the lightest of touches, the man never encroaching on the ballerina’s space. All is clean, sharp, an unerringly musical. Or at least it should be. The performance on the 21st lacked dynamism and focus. Veronika Part’s dancing in the adagio was twice as grand as it had been at the gala last week, but also more wobbly and insecure, despite the elegant, sure partnering if Cory Stearns. Why does she vary so from performance to performance? (At the matinée on the 22nd, Polina Semionova gave an impeccable, almost breezy account of the same adagio.) At the matinee, Stella Abrera was again in top form.

The matinée also included an appearance by Natalia Osipova and Ivan Vasiliev in the third movement. Both danced with their usual whiz-bang energy and attack, but Vasiliev looked somewhat strained by Balanchine’s highly stylized, elongated movement. It’s not really his thing, but it was fascinating to watch him try to embody the style of the refined Balanchine danseur. The matinée performance of Symphony was better over all, but the night before there had been a few highlights, most notably the dancing of James Whiteside in the first movement – my, what beautiful sissonnes you have! – and the duo of Herman Cornejo and Xiomara Reyes in the high-spirited scherzo. The two seemed to be having a grand old time, and how can one blame them, with such effervescent music bobbing and bubbling in the background? And how Cornejo flew offstage with every exit, and dashed on with every entrance, arms opening warmly to the audience! He made every moment count.

You must be logged in to post a comment.