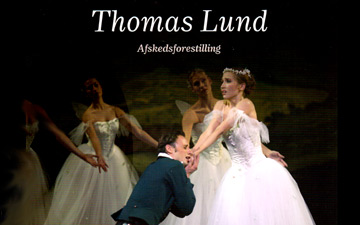

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

cr Kermessen

Royal Danish Ballet

La Ventana, Kermesse in Bruges

Copenhagen, Royal Theatre

3 and 4 May 2013

kglteater.dk

Gudrun Bojesen interview, including her work on La Ventana

Is this double bill, I wonder, the final chapter of Nikolaj Hübbe’s Bournonville makeover? These new productions of La Ventana and The Kermesse in Bruges follow his own versions of the ‘big three’ – La Sylphide, Napoli and A Folk Tale – and, with the addition of the surely sacrosanct dancing-school scene from Le Conservatoire, they complete the set of surviving ballets likely to hold their place in the repertoire outside the sheltered environment of another Bournonville festival. His choice of producers – solodanser Gudrun Bojesen for La Ventana (interview), former solodanser Ib Andersen for Kermesse – is significant in that neither of them has set a Bournonville piece on this company before, and neither of them is associated with the ‘old guard’ Bournonville team which was responsible for most of the productions over the last decades: Le Conservatoire always excepted, all of the active Bournonville repertoire now bears Hübbe’s own stamp.

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

Although she was working on the shorter of the two pieces, Bojesen in a way had the harder job. Bournonville made La Ventana’s famous mirror dance first, as a speciality number for two of his favourite dancers, and developed the rest of the ballet afterwards to exploit its huge success. He added a thread of a story but it remains essentially a divertissement – a jewel, but one needing a setting to show it off properly. Bojesen rejected any thought of a modern-dress production and instead set out to create a more authentically and intensely Spanish atmosphere. That the outcome is not entirely successful is mostly due to a stage version of ‘first novel syndrome’ – she has a lot of ideas and has tried to include them all, and the result is somewhat over-busy. For instance, though I like her idea of a scene-setting prologue, by the time she’s introduced not only a bored waiter, a guitarist, a flamenco singer, and a passing tourist who may or may not be Hans Christian Andersen on his travels, first-time viewers are beginning to wonder if they’re ever going to get to the ballet itself. On a second viewing it actually makes a lot more sense, and with a bit of tweaking of exits and entrances it could be genuinely effective – but most people will only see it once.

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

The dancing, when we do get to it, is much more simply staged and it’s a pleasure to see this lovely choreography again. Diana Cuni – one of the company’s finest Bournonville dancers – leads the first cast, with Alexander Stæger as her suitor; Amy Watson and Marcin Kupinski are their alternates. Stæger is the stronger actor of the two men and in this version that’s important; he was also dancing with a lot more zip and apparent enjoyment than I’ve seen from him before. In the pas de trois I particularly enjoyed Lena-Maria Gruber’s calm authority and – in the other cast – Gregory Dean’s new-found confidence: maybe his recent success as Romeo has moved him up into a higher gear.

Ib Andersen’s new Kermesse is an instant success, a production to last for decades. First of all, it’s gorgeous to look at: Jérôme Kaplan sets it exactly where Bournonville wanted it – the middle of the 17th century – and takes his inspiration from the great artists of the time: Vermeer, Rembrandt, Frans Hals and others, all politely thanked in his programme note for their ‘invaluable help’. The sets are simple, the costumes anything but: those for the principal dancing characters are traditional and appropriate, but for sumptuousness and sheer beauty they’re outdone by some of those for the corps de ballet and for the extras. Two men who are literally porters, only onstage for seconds, have elaborately detailed outfits, made – like all the rest – from beautiful fabrics, and the women of the corps de ballet owe both Kaplan and the theatre’s costume department a huge bouquet for dresses which both move beautifully and make their wearers look fabulous.

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

Andersen was a solodanser here for five years, till Balanchine lured him away to New York, and a brilliant exponent of Kermesse’s leading role in his time. His production follows the path of tradition, more or less. He’s changed some of the choreography for the corps in the first scene, in the belief that it isn’t genuine Bournonville: assuming he’s right – and I’m in no position to argue with him – my only regret is that he’s got rid of the traditional clogs. That may be a great relief for the dancers, who are often quoted as hating them, but I really miss the noise they made – the music sounds only half-there without them. Otherwise all is familiar, through to the sweetly decorous ending as the leading players join hands in a row across the front of the stage and bow as the curtain falls. (I do wish, though, that Andersen hadn’t decided to return to the tradition – dropped in the last production – of having the rich, pushy lady in the third scene made up as black.)

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

cr Kermessen

Structurally and dramatically, Kermesse is an odd piece. Briefly, it’s about three brothers who rescue an alchemist, Mirewelt, from a street attack and are rewarded with a magic gift each: a ring for Gert, making him irresistible to women, a sword for Adrian which makes him invincible in combat and for Carelis, the youngest, a viol which makes everyone who hears it start to dance. (The last one always seems out of line with the others but I guess it means Carelis can literally make everyone dance to his tune – it’s the gift of power, perhaps.) Originally there was an element of satire in the ballet, but that’s long gone and it’s now a mixture of comedy and romance, with a moral just visible under the surface as each brother in turn realises he doesn’t need the prop of magic in order to find happiness.

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

To start with it seems as if we’re going to be spending the evening watching the development of the love affair between Carelis and the alchemist’s daughter, Eleonore, but in fact they are more or less sorted by the end of the second scene and the spotlight switches to the other brothers. The one with the ring, Gert, is a bumbling but endearing fool who can steal the show in the hands of a good comic, Adrian has a strong solo, Eleonore’s two friends and their mother have a lot to do and of course there are some nice character roles for the older dancers – so it’s very much a company piece. There are 19 named roles, most of them double cast: from the less important characters I’d pick out James Clark and Charles Andersen as two gentlemen – the villains of the piece in so far as there are any – Gitte Lindstrom having a wonderful time as the widow besotted by Gert, Dean again in the divertissement, Stæger again leading the spirited Slovanka, and Astrid Elbo, a young dancer with a strong stage presence, as the tightrope dancer. Eleonore’s friends were all well played, with Alexandra lo Sardo outstanding as Gert’s spitfire girlfriend and Cédric Lambrette was an increasingly camp, frantic and funny butler.

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

Benjamin Buza, who is making quite a name for himself this season, danced Adrian in both performances, substituting for Jonathan Chmelensky in the first cast as well as appearing as scheduled in the second one: he’s technically secure and dramatically convincing, a real asset in the making. Gert was shared between the experienced Nicolai Hansen, making his debut the night I saw him, and the much younger Jon Axel Fransson, both of them appealingly funny. Buza and Fransson belong to what is beginning to look like a whole new generation of promising young dancers still in their first two or three of years as full corps de ballet members, and joined this season by even younger talents – three of the four romantic leads were still apprentices this time last year. Ida Prætorius has attracted the most notice so far, especially for her Juliet a few weeks ago: she’s a real ingenue type, blonde, very pretty and sweet, whilst the second cast Eleonore, Stephanie Chen Gundorph, is a quite different dancer, dark, quieter and at present perhaps a rather more complex character. Both were enchanting. Gundorph’s Karelis, Andreas Kaas, is their contemporary, dancing his first big role: he doesn’t have quite their stage presence yet but his Bournonville dancing is already stylish and assured. Prætorius, in the first cast, had Alban Lendorf as her partner: he was a rather serious Carelis, taking his responsibilities as both suitor and keeper of the magic viol to heart; his dancing was pure delight.

© Costin Radu. (Click image for larger version)

In fact delight was the keynote of the whole evening: complaints and quibbles notwithstanding, I was very happy to see the whole company reclaiming their ‘joy in dancing’, the Bournonville essence which is fundamentally what keeps these old ballets alive.

You must be logged in to post a comment.