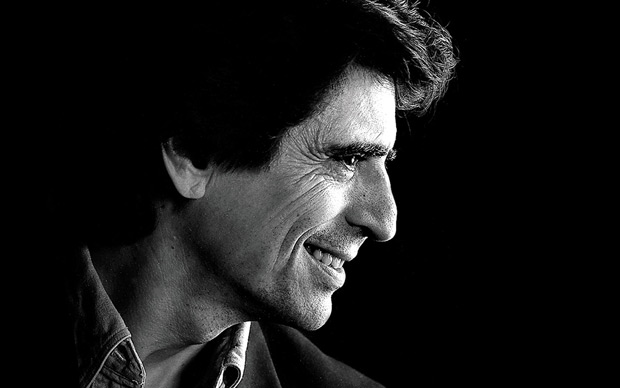

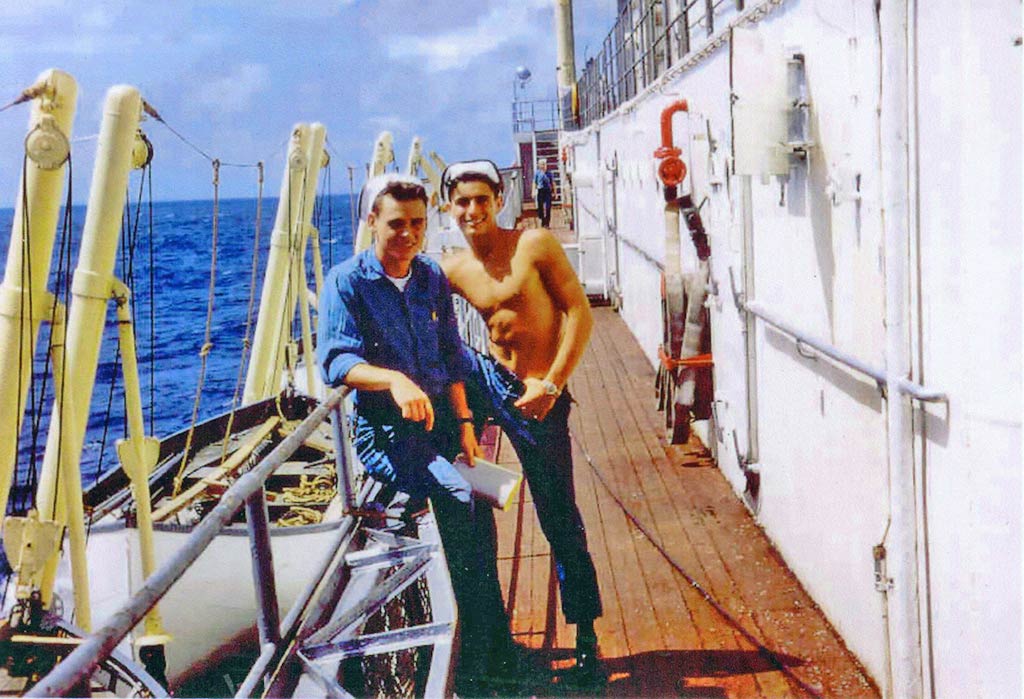

© Philip Bermingham, courtesy Edward Villella. (Click image for larger version)

villella.org

www.miamicityballet.org

Edward Villella, Back in Town

© and courtesy Edward Villella. (Click image for larger version)

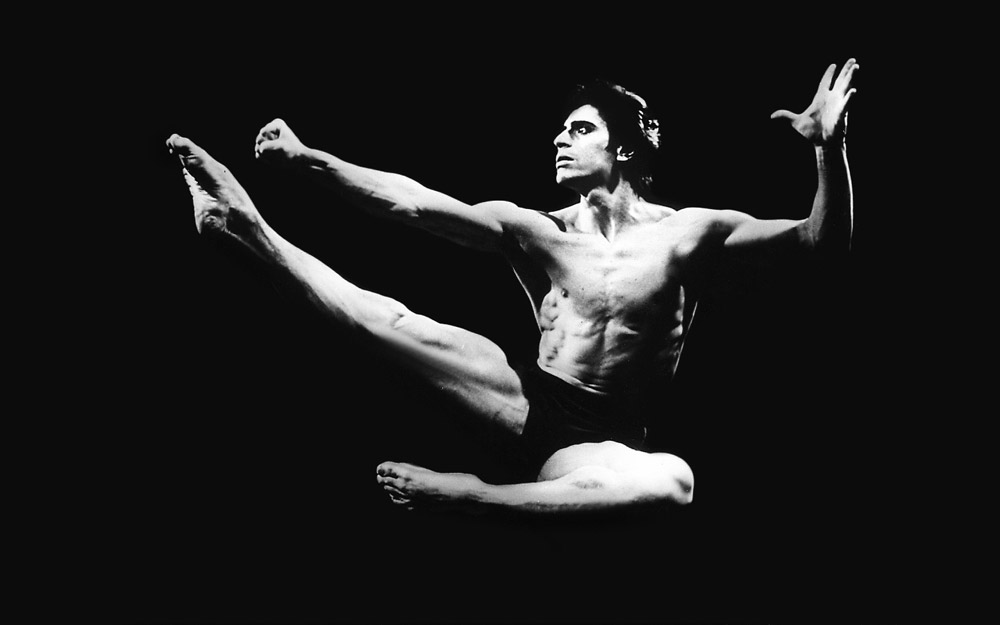

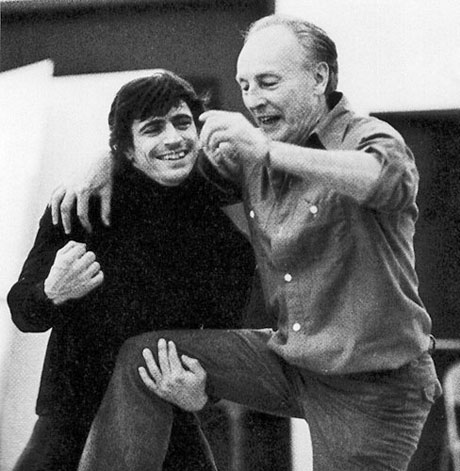

© George Platt Lynes, courtesy Edward Villella. (Click image for larger version)

Even as a student, there was something about him that commanded attention. Watching him stretch in an empty studio, Jerome Robbins sensed a focus and innocent eroticism in the young dancer that would inspire him to make Afternoon of a Faun. Not long after Villella joined the company in 1957, on his twenty-first birthday, Balanchine gave him the role of the Prodigal Son in his 1929 ballet. As Villella writes in his 1998 memoir (entitled, what else, Prodigal Son), “it was the first ballet that made me think and start to expose my real self.” More than most dancers – or artists of any kind – Villella was always himself onstage, a dancer full of vitality, sensuality, and joy. There was nothing fussy or stylized about him, though his dancing had enormous style. If you want proof, I suggest that you go check out the blurry video of Midsummer Night’s Dream at the New York Public Library. In his shimmering costume, with silver dust in his hair, Villella appears to skim across the stage, feet beating together like hummingbird wings. In the words of the critic Robert Greskovic, he was “elegant yet impetuous, powerful yet delicate, straightforward yet sly, romantic yet classical.”

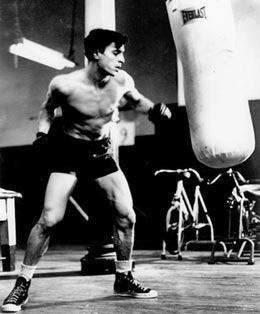

© Bill Eppridge, for Life Magazine, courtesy Edward Villella. (Click image for larger version)

After an early retirement brought on by a series of injuries (due in part to his discontinuous training), Villella went on to lead the Eglevsky Ballet and Ballet Oklahoma. Finally, in 1985, he was lured to Miami, where he became the founding director of Miami City Ballet, his home for the last quarter century. In that period, the company (and the related school) became one of the leading interpreters of Balanchine outside of New York (some would say the leading exemplar). In 2010 the troupe appeared for the first time on Dance In America; the year before it had had a highly successful New York run. In 2011 it performed to packed houses (and glowing reviews) in Paris. Even so, trouble was brewing backstage. Disagreements with the board of directors over repertory and artistic control and money issues, eventually led to an acrimonious split. It was a sad ending to a truly remarkable undertaking. Villella, now back in New York, is ready to move on to the next phase. A few weeks ago, I caught up with him in New York and asked him about his plans. What follows is an edited version of our conversation.

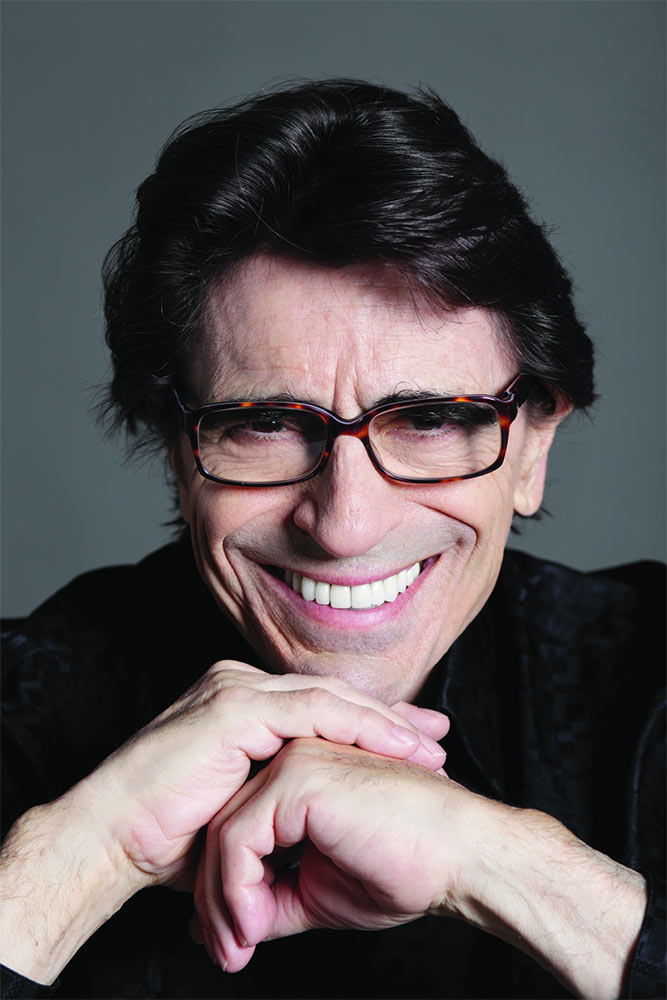

© Gio Alma, courtesy Edward Villella. (Click image for larger version)

How is it to be back in NY?

It’s absolute heaven. I feel like I’ve been culturally deprived for twenty-five years. When I first got down to Miami people would come up to me and ask: “what are you doing here?” We had to start from nothing and create new habits. The habit there was to have a major company pass through, which meant Giselle, Sleeping Beauty, the nineteenth-century spectacles. That’s all they knew. It’s a resort town, a clubbing town, it’s very shallow culturally. And it’s very difficult to raise money there. But I knew what I was getting into. I had the opportunity to make a company from the ground up, so all of the mistakes would be mine, and all of the successes. I wanted to make a company that I would have wanted to dance in, from a dancer’s point of view.

Where are you living these days?

We bought a brownstone up in Hamilton Heights [in Harlem]. It’s beautiful up there. The neighborhood is in a state of transition, because of Columbia University. It’s very neighborly. My wife is a former Canadian figure-skating champion, and there’s an ice rink nearby. She hasn’t skated in twenty-five years.

© Martha Swope, courtesy Edward Villella. (Click image for larger version)

No skating rinks in Miami?

There are a lot of things here that there aren’t in Miami.

Do you think Balanchine could have run New York City Ballet company the way he did if he were alive today?

It would have been a huge struggle. But of course he had Lincoln Kirstein. Lincoln told me once: “you know what I do? Protect Balanchine.” I had to do it all. They used to call us the “Miami Miracle” because we got things done. I took a year and a half to raise visibility and introduce the idea of a new ballet company to the community. I predicted that if we did our up-front stuff correctly, we’d have 2,000 subscribers. On opening night [in 1986] we had 4,500 subscribers. I looked at the map: there was Miami, and half an hour up the road there was Fort Lauderdale, and half an hour the other way Palm Beach. Naples was just up the West Coast. That gave us four different venues so I could set up a circuit. The advantage of that is that it gives dancers multiple opportunities to perform, and with dancers, no matter how much you provide in the studio, the real progress happens onstage. We reached out to the community in Miami, Fort Lauderdale, and Palm Beach. I treated each venue equally. We would do long weekends in each place. I also got us touring in the first season.

© George Platt Lynes, courtesy Edward Villella. (Click image for larger version)

Why was touring so important to you?

We had to raise our visibility. Also, it was a way to be eligible for national funding. But twenty-five, twenty-six years ago, there was very little Balanchine in the rest of the country. That basically put us on the map. My premise was, if you’re going to do the work, do it the way it was originally intended. I had been studying these works for years and years.

© Bert Stern, courtesy Edward Villella.

Did you bring in coaches?

It was difficult to afford, but I did. I brought in Allegra Kent to coach Serenade and one or two other things. I had prepared five years of programming before we opened so we would have an idea of what we wanted to be when we grew up. One of the works I wanted desperately was the full-length Jewels. We were the first company outside of New York City Ballet to do it. But we approached it very carefully. First we did Rubies. It’s the smallest of the ballets – we had nineteen dancers at the time – and I knew it well. The next was Emeralds, and then the largest was Diamonds, so we had to wait for that. The three “jewels” are still around: Violette Verdy, Patricia McBride, and Suzanne Farrell. I invited Violette down to coach Emeralds, but I also did two or three works that she was associated with and had her coach those as well. And I did the same with Patty McBride and Suzanne. We performed Jewels at a gala in Miami, one in Fort Lauderdale, and one in Palm Beach. That raised our visibility and helped us raise most of the money we needed to cover the production. Then I waited until the following year [1992] to put it into the repertory. I was really milking it.

Edward and Allegra: the originals in Bugaku (10 minute video)

How did you know to do that?

I’ve been around. I had a small group of dances from NYCB and we used to tour, so I had a little bit of background. Necessity is the mother of invention. Maybe it was ambition. It was mostly Balanchine for the first six or seven years and the premise of that was, one, I knew it, two, no-one else did it. But I had to start gently; I couldn’t throw too many sophisticated ballets at them. The first program, we opened with Allegro Brillante, and then I had Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux. I also had works by two other choreographers, Richard Tanner and our resident choreographer at the time, Jimmy Gamonet de los Heros. But the key was Allegro, because that way people could see something that looked very nineteenth-century. Balanchine once said, “in Allegro Brillante you will see all I know about classical ballet.” That was a very gentle way to begin.

Did you commission new works?

A few. But my premise was to present only masterworks. I wasn’t interested in “oh my god, some choreographer somewhere made a nice ballet, so now everybody is running after him.” I didn’t do that. I was very patient, I knew what I wanted.

© and courtesy Edward Villella. (Click image for larger version)

You commissioned a work from Ratmansky in 2012, Symphonic Dances.

I adore the way he works. The dancers loved him, and he loved the dancers. He once said our guys were his favorite dancers to work with. It took me about 3 years to get him down there and raise the money. I commissioned very few new works, because there was never enough money. I knew we couldn’t live on commissions. Paul Taylor, Twyla Tharp, Jerry Robbins, Balanchine, that was the spine. I spoke before every performance in order to illuminate certain areas of these complicated neoclassical works. I gave the audience insight into what they were about to see.

Was the Cuban community in Miami a source of support for the ballet company? Cubans are known for their love of ballet.

Not really. Early on, the Cubans would come if there was a Cuban onstage. They didn’t know Balanchine, they’d never seen it. I remember when we were just starting out, a defector or two would come, and we would be jammed. But for the most part, if we had half a house, that was a big deal. We were generally in the 1,000-seat range.

Did you have the critics’ support?

After a while. It took about five years. At the beginning, my programming got clobbered. More than once, the critics complained about my presenting ‘the same old Balanchine.’

Where did you find your dancers?

About four or five of our original dancers came from Oklahoma [Villella was the artistic director of Ballet Oklahoma from 1983-1985]. And then we announced there was a new company forming. We found dancers who had enough ability but I knew I would have to train them. So I devised a class that would serve the repertoire so that they would have the attack and the Balanchine vocabulary.

Edward Villella talking about starting ballet and his fathers disapproval…

In your memoir, Prodigal Son, you mention what a hard time you had finding a class that gave you what you needed.

You know I didn’t dance for four years, between the ages of sixteen and twenty [while he was getting his degree at Maritime College], and then suddenly I joined City Ballet, and I thought, well, everything will be fine. Four years later, I could still jump. I was so naïve, I thought I could just go out there and fly around. It was critical for me to create a class that would allow these dancers to dance not only Balanchine and Robbins and Taylor but to do almost anything.

© and courtesy Edward Villella. (Click image for larger version)

What were the unique aspects of your class?

The music was key. The other part was the upper body. How do we move? For instance, the first exercise I gave at the barre after pliés, tendu battement, had three rhythms, so they got used to that. I had a fabulous pianist, Francisco Rennó; we really understood each other. I gave all these intricate steps, and he would play and embellish what I was doing. He played a lot of jazz. I looked at the ballets and figured out what kind of barre would benefit these dancers and give them an insight into the musicality, the attack. I worked to the back of the room, away from the mirrors, a lot. If I look at a Balanchine ballet, it’s a series of simplicities that make up an apparent complexity. So I took my time. We didn’t do Agon until about the fifth year.

And then there’s the speed. I’ve never seen Oberon’s solo (the Scherzo) danced as briskly as you did in the 1966 film of Midsummer Night’s Dream.

The thing about that movie is that Robert Irving conducted, and it was pre-recorded. It has never been played as fast. That was the point. Balanchine wanted the steps to look like I was just skimming the floor. Once you get it, you feel like you’re flying.

© Gio Alma, courtesy Edward Villella. (Click image for larger version)

Did you do a lot of coaching in Miami?

Yes, and I taught class every day. What I was looking for was speed, and an articulation of the difference between the Russian plié and the Balanchine plié. The Balanchine plié is very much like the Danish. What the Russians do is squeeze out the plié, whereas with Balanchine the energy never stopped. The end was the beginning. This was an important premise to get across to the dancers. And then there there’s everything you do with the upper body and the port de bras and how all those lines relate to each other. My premise is, don’t dance the steps, dance the music. The music shapes the gesture.

It sounds like you were giving them an extra layer of information that you didn’t always get when you were dancing.

Balanchine rarely talked to us, and certainly not to the guys. He would say very very few things. With Prodigal Son, he taught me the opening in half an hour, the closing in half an hour, the pas de deux in an hour, and then I never saw him again. I had a conversation with Arlene Croce about it once. I said, I wish he’d given me some thoughts, some insights. I don’t understand why he didn’t break it down. And she said: “maybe he wanted to see what you would do with it.” One time in particular, when I was having trouble with the pas de deux, he said, “no, not right, not right, Byzantine icons, dear.” So I went back and looked at some Byzantine icons and right there I understood the whole port de bras. At some point he started to talk about Apollo. He talked about soccer steps, and a matador watching the bull go by, and an eagle on a crag, waiting to swoop down. They were all very masculine images. There is a temptation to reduce the ballet to a pose. But Balanchine told me: “Apollo is a rascal.”

© Martha Swope, courtesy Edward Villella.

How was your approach to directing the company different from his?

I wanted the dancers to know what I knew. When I came to New York City Ballet I hadn’t danced for four years, so it was critically important for me to analyze the ballets. But I had no points of departure. One day Balanchine said, “I’m going to bring this Dane, Stanley Williams. He knows how to make people move.” So Williams comes, and I take the first class, and I say, “ah!” There was a simplicity, a logic, a structure, that I had been missing. Balanchine’s classes were structured around choreographic ideas. He would give maybe a twenty-minute barre. And I couldn’t survive that way. I needed more. Williams and I became very close; he became one of my best friends. He was evolving and developing as a teacher. He said something very interesting: “you think you’re getting a lot from me, but I can’t begin to tell you how much I’m getting from you.” He was learning how to take things apart.

Miami City Ballet has a lot of Latin dancers. Does that partly explain the company’s warm, extroverted style?

Most of our Latin dancers were Cuban, and where do the Cubans get their ideas from? Russia. So it was mostly the nineteenth-century style. It was a big deal to get them from where they were, in the 19th century, into Stravinsky and Modernism. It took a long time. So the idea of the company being Latinized is not completely valid. The thing is, every dancer knew who they were onstage. I explained the manner, the style, the points of departure. So they knew not only who they were, but how everything related to everything else. We used the premise of the company as a family. Plus, as the school progressed, we took all our dancers from our school. This whole thing was crafted. Nothing just happened.

© and courtesy Edward Villella. (Click image for larger version)

Did you give Lourdes Lopez, the new artistic director at Miami City Ballet, any advice when she took the reins?

I met with Lourdes and I said to her, look, what you should do is make it your own. Feel confident in your taste and make it your own.

What have you been doing since you left Miami?

The thing I don’t want to do is repeat what I did before: raise money and deal with a board. There is so much ignorance out there. It’s terrible to say, and I said it maybe too many times. But the reason I’m here is because I have this knowledge and this background that I’m dying to pass along. And I understand that what we do is entertainment. It’s not just serious art. It’s wonderful qualitative entertainment. But you have to have some kind of background to understand the quality of the entertainment that’s before you.

© and courtesy Edward Villella. (Click image for larger version)

What are your plans?

I’ve done masterclasses and coached Prodigal, and spoken at the Paley Center for Media. There’s a company out in New Jersey, the New Jersey Ballet, who I’m working with. I love to coach, I love to teach. I spent twenty-five years doing fourteen to sixteen hour days. For me it was terrifically exciting, but then there’s the other side of it. It’s enervating and it’s hard to do. I don’t want to get tied down. I’d like to write a book. But I want to wait until September, because I want my mind to be clear. I don’t want to be overly influenced by the negative.

Do you feel bruised by your experience in Miami?

For me it started 25 years ago. I kind of knew. The other part was, we had just performed in Paris [in the spring of 2011]. We did fourteen ballets, seventeen performances, over the course of three weeks, and we sold something like 96-97 percent of the seats. They danced like I’d never seen them dance before. I did forty interviews, and every interview started with the same question: “how did you get them to dance that way?” Then we came back from Paris with a couple million dollars in debt. As far as I was concerned, my contribution ended in Paris, because there was nothing else I could do. I did two more seasons, but that was it.

From the early 90s, an 8 minute profile of Edward Villella where he talks about his life and influences and featuring much footage of him dancing.

Do you have any regrets at all about anything you said or did in Miami?

Not really.

Are you following the company closely?

No. It’s not so much taking a step back, but it’s no longer my company.

© Marina Harss. (Click image for larger version)

What do you think distinguishes the dancers you performed with over the course of your career from dancers today?

Probably the way Balanchine developed us. If you look at the array of these women – Violette Verdy, Patty McBride, Suzanne Farrell – they were just amazing personalities, and he never interfered with that. He knew us so well, and he made the works around us. Like the guy in the third movement of Rubies, flying around, getting chased. That’s how I grew up. We used to chase each other in the streets. It was uncanny.

Do you miss dancing?

[His eyes light up, and he nods, with a roguish smile.] I’m looking for the devil’s 800 number.

[…] Edward Villella is back in town, unbowed by his Miami City Ballet experience and ready to begin the next chapter of his life. I sat down with him recently at a café around the corner from his Hamilton Heights brownstone to talk about his life in dance, Balanchine, his experiences in Miami, and his plans for the future. You can read the interview here, in DanceTabs. […]

Again, one of Marina’s superb interviews. Fulsome, satisfying, and edifying.

I’m sure you know that Edward Villella is slated to take on the Chairmanship

of the USA IBC’s jury at Jackson in 2014. His was a consistent presence at

the end of each competition, and a number of his dancers either came to compete or were awarded contracts at the conclusion of a given Competition.

It will be interesting to learn just who he is choosing as jurors.

Thanks again, Marina.

Terrific interview!

Thank you Eddie for being one of the greats of our generation. I was always inspired by your performances. You always took my breath away. Your performances and your presents on stage was electrifying.

The interview was very good. Thank you. I was a founding member of the Miami City Ballet in 1986. I wanted to acknowledge the excellent work of Elyse Borne, the company’s first ballet mistress. She is not mentioned in the interview, but she was instrumental in getting the company up and running. She was always such a great coach and approached the work with humor and grace. I think some credit is due.

Thank you all for your kind comments. It was a fascinating conversation. And thank you Mr. Lineberry for mentioning Ms. Borne, who served as ballet mistress at Miami City Ballet for eight years (and San Francisco Ballet for six) and has staged Balanchine ballets for everyone from National Ballet of Canada and the Royal Ballet to the Mariinsky and the Royal Danish Ballet.

A truly remarkable person who immeasurably increased the value of living as a contemporary. I thought the Miami Ballet under his leadership was a true national company and deserved more recognition from the national scene. One could almost feel the maturation of the dancers with every succeeding performance. The interview is a treasure. Thank you. BLM

After moving to the Miami area from New York I was disappointed by the lack of good entertainment in the midst of all that glitz – until – someone told me that Edward Villella and Company were in Miami Beach. Edward was one of the “greats” that made NYC. SAVED!

Edward never disappointed – his presentations were as skilled and as beautiful as were the presentations by the New York City Ballet during the years that he danced there. We were so lucky to have him as our resident Artistic Director. For me Edward made the Miami Area liveable.