© Dave Morgan (Click image for larger version)

English National Ballet

A Tribute to Rudolf Nureyev: Petrushka, Songs of a Wayfarer, Raymonda Act III

London, Coliseum

25 July 2013

Gallery of Pictures (Cast 1) by Dave Morgan

Gallery of Pictures (Rojo cast) by Foteini Christofilopoulou

www.ballet.org.uk

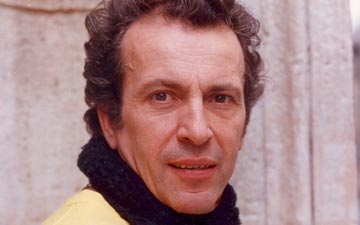

You wouldn’t have guessed from English National Ballet’s poster and programme cover that the company was paying homage to Rudolf Nureyev. Whoever dreamt up the ‘edgy’ image of a Picasso look-alike in a vast black ruff and bondage cords had evidently never seen Nureyev or Petrushka.

Fokine’s 1911 ballet opens the triple bill, after a filmed tribute to Nureyev on the 20th anniversary of his death and the 75th of his birth. The speakers included Lynn Seymour, Michael Coleman and Gary Harris, all of whom had worked with him. Harris acknowledged that Nureyev had effectively saved London Festival Ballet (as ENB was known then) in the 1970s by performing and touring with it, as well as mounting his own productions of Romeo and Juliet and The Sleeping Beauty.

© Dave Morgan (Click image for larger version)

Petrushka was one of Nureyev’s favourite roles. He first danced it with the Royal Ballet in 1963 and then over the years with the Paris Opera Ballet, Joffrey Ballet, Festival Ballet, Ballet de Nancy and finally the San Carlo Ballet in 1990, not long before his death at 53. In my recollection, he was wrong for the role. Petrushka needs a performer who can obliterate his physique and personality, transforming himself into a sawdust-stuffed puppet with ungainly wooden limbs. Nureyev acted the role, pulling a pathetic face and dying histrionically. The most memorable Petrushka I ever saw was David Bintley in the Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet (now Birmingham Royal Ballet) production. I even believed I saw blood on his mitten when he extended it to the crowd as he collapsed.

ENB has borrowed BRB’s Petrushka sets, front cloths and costumes, contributing a few of its own from the past. Though Alexandre Benois’s setting (one of his many designs for Petrushka) looks wonderful, ENB’s production fails to come alive other than as an historical curiosity. Petrushka always was antiquated, set in 1830, when Russians celebrated the three days before Lent with a Butter Fair in the Admiralty Square in St Petersburg. Stravinsky drew on Russian folk songs for the music; the puppets were familiar figures from folklore; the original subtitle was A Burlesque Ballet in Four Scenes.

© Dave Morgan (Click image for larger version)

The main characters are indeed caricatures. The Charlatan who manipulates the puppets is a rogue, as his name indicates. Petrushka is a hopeless loser; the Ballerina doll a parody of air-headed femininity; the Moor an exotic savage with a scimitar. So, is it acceptable to cast a dark-skinned dancer (Shevelle Dynott on Thursday night) as the Moor instead of blacking-up a white performer? No worse, I guess, than asking an intelligent female dancer (Nancy Osbaldeston) to be a witless doll or a talented male dancer (Fabian Reimair) to lose control over his limbs. Or to put an uncredited extra in a fur suit on a hot night because Stravinsky had written music for a performing bear.

But, like the crowd of revellers, we need to believe in these non-human characters. Above all, we need to be convinced by the crowd’s reactions to each other and the puppets’ drama. Fokine was adamant that the lively fair-goers should seem spontaneous, preoccupied with their own interests and not responding in unison to the music’s rhythms – unless they emerge for brief, specific dances. They must remain distinct from the puppets, whose actions are dictated by Stravinsky’s musical descriptions of them. ENB’s crowd of company members and youngsters are all too obviously drilled into making way for each vignette, standing in a semi-circle instead of jostling.

© Dave Morgan (Click image for larger version)

So the action fell flat, not helped by unatmospheric lighting. The sky should darken as the snow falls in the last scene, which takes place as night falls. The Charlatan (James Streeter) returns to his puppets’ booths, probably after having a drink or three, remembering when he used to show tame bears instead of temperamental puppets – a quote from A Bullet in the Ballet, by Caryl Brahms, who wrote of Petrushka: ‘In his inability to express himself, he is the most articulate figure that the Ballet knows.’ His spirit triumphs in the final moments, though only we and the Charlatan witness his defiance.

Reimair, making his debut as Petrushka, was poignant without stirring strong emotions. Dynott was a cheerful, imperturbable Moor, Osbaldeston a china-doll-faced Ballerina with dagger-sharp feet and a surprisingly strong personality. As street dancers, Shiori Kase and Jung ah Choi competed valiantly. But it does look as though the present company has little continuity with Festival Ballet’s Diaghilev heritage.

© Dave Morgan (Click image for larger version)

Song (or Songs) of a Wayfarer, the middle duet, was created by Maurice Béjart in 1971 for Nureyev, with Paolo Bortoluzzi of Béjart’s own Ballet du XXe Siècle. I saw Nureyev dance it in 1983 at the Coliseum with the very young Patrick Armand, who subsequently joined London Festival Ballet. Béjart apparently envisaged the duet as a depiction of a restless dancer going from country to country without a homeland to which he could return. Set to Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, it’s clear that the Wayfarer’s companion is his dark angel, his Messenger of Death: presciently, the duet could have been about the scourge of AIDS, which killed Nureyev, Bortoluzzi and Jorge Donn, another great Béjart dancer.

As a technical exercise, a display of male prowess, the duet is a test of classical placement. Both dancers face the audience with nowhere to hide. Béjart took Nureyev’s favourite steps and stance in ‘overcrossed’ fifth position and gave them a modern dance twist without distorting them unduly. In the Nureyev role, Vadim Muntagirov is a golden youth with the ideal physique of a supple, long-legged dancer – which Nureyev wasn’t. Esteban Burlanga, who leaves ENB at the end of the season, has to strive to match Muntagirov’s romantic elegance and assert himself as the all-knowing survivor. Both succeed in complementing each other’s strengths. Baritone Nicholas Lester sings Mahler’s bitter-sweet songs sympathetically, while the choreography emphasises every repeated phrase. I admire Béjart’s resolute spareness even as I resist his emotional manipulation.

© Dave Morgan (Click image for larger version)

Muntagirov proves what a splendid danseur noble he has beome in the closing divertissement from Act III of Raymonda. Nureyev had first mounted this version for the Royal Ballet’s touring company in 1966. ENB has borrowed Barry Kay’s opulent set and costumes from the Royal Ballet, enabling the Coliseum season to honour Nureyev with a suitably lavish classical ballet spectacle.

© Dave Morgan (Click image for larger version)

He had cherry-picked the prettiest, trickiest variations from all three acts of Petipa’s 19th century ballet and added more for the men to do. Muntagirov tackles his Nureyev solo with grace and precision; the male quartet are less exact, though they land their double tours en l’air without fault. The first three female variations are carefully controlled by Fernanda Olivieira, Nancy Osbaldeston and Erina Takahashi. Only Crystal Costa in the fourth one is insouciant enough to disguise just how difficult the solos are. Daria Klimentova is radiant as Raymonda, with Muntagirov as her attentive partner. She’s a trifle too abrupt in her Hungarian variation, which could do with a more luscious womanliness.

© Dave Morgan (Click image for larger version)

The Tribute bill is a well-chosen one, showing off the company while commemorating its links with Nureyev. The season has been so short that the dancers haven’t had time to grow into their roles. They look as though they’re remembering instructions rather than relishing the ballets. They could take a lesson from the Trocks’ account of Raymonda – sheer joy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.