© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

Australian Ballet

Cinderella

Melbourne, State Theatre

18 September 2013

australianballet.com.au

At the end of Cinderella’s first act, and in the wake of a flowing silk curtain sweeping across the stage (a temporary replacement for the State Theatre’s usual staid, yet gorgeous, red velvet), I suddenly became aware of my surroundings. Mouth agape, notebook hanging negligently off my knees, pen lost somewhere beneath the seat in front of me… I had been completely transfixed by the magic of the stage. Perhaps it’s no surprise, really. This Cinderella, the hotly anticipated centerpiece of the Australian Ballet’s 2013 season, is sensationally, luxuriantly, and extravagantly beautiful and, quite frankly, a production I would pay to see again (and again) in a heartbeat.

© Jerome Kaplan. (Click image for larger version)

Later, as I began to sift through my feelings about the ballet (and in the absence of any of the usual scribbled notes to guide my thoughts), I realised that the success of this production has as much to do with Jérome Kaplan’s ballsy and occasionally outrageous costume designs as with Alexei Ratmansky’s deft and elegant choreographic sequences or the sublime dancing by the artists of the Australian Ballet. The choreography alone is thrilling: sweeping, elegant and sparkling with humour inspired by the characters in the story. Despite the significant stylistic shift from their previous program of Romantic ballet works, the company looks confident and well rehearsed, seeming to relish the challenges inherent in bringing Ratmansky’s vision to life. After all, this is a vision that is unapologetically big; though Cinderella may retain some elements of a classical production, including the basic narrative outline, it infuses heritage and tradition with wit and a kind of rosy, cinematic wash.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

For audiences abroad that have seen Ratmansky’s Cinderella performed by the Mariinsky Ballet (a production that was still touring internationally as of last year), I should hasten to note that this is a new ballet rather than a remount. According to the lead dancers Leanne Stojmenov and Daniel Gaudiello, Ratmansky appeared to treat this Cinderella as an entirely new work, setting choreography on the company in their home studios. There are now two original Alexei Ratmansky Cinderellas out there in the world, although the Australian Ballet’s version, made more than a decade after Ratmansky’s experiments in 2002 with designers Ilia Utkin and Yevgeny Monakhov, has a very different look, largely thanks to Kaplan’s designs. Both Cinderellas, however, utilise Sergei Prokofiev’s romantic and lush score, performed here by Orchestra Victoria and conducted by Chief Conductor Nicolette Fraillon. Ratmansky has previously expressed a desire to redo Cinderella, and this was his opportunity to do so.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

Cinderella begins with our heroine (Stojmenov) picking the laundry off the line. She weeps at the foot of an enormous, sepia-washed Edwardian style painting – a representation of a long-lost and much missed mother. This picture of quiet grace is shortly contrasted by the appearance of the dreaded Stepmother and her two awkward daughters, Skinny and Dumpy (Amy Harris, Ingrid Gow and Halaina Hills). Oscillating between obsequiousness, coquetishness and driving ambition, Harris’ Stepmother is comedic gold. Harris is a fine dancer and an excellent performer, and the sense of this character as the ultimate stage-mother/micro-manager shines through, enhanced rather than inhibited by her shockingly pink frocks, headpieces and toothy grins.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

For the Stepdaughters, Kaplan has crafted shapes where there are none, defining outrageous silhouettes. The Dumpy Stepsister (performed by the anything-but-dumpy Halaina Hills) sports a bulbous knot on her head – rather like a spectacularly sculpted beehive – and a bouncing bubblegum bubble skirt that sways and undulates with every step. In an absolute nail-on-the-head design moment, the Skinny Stepsister (Ingrid Gow) wears her pointe shoes laced over knee-high stripey turquoise stockings. Much later, stiletto hats (perched jauntily, heel up and toe down) make their impressive debut on three very silly heads – a commentary, perhaps, on the changeable nature of women’s fashion.

The cruelty inflicted on Cinderella comes through the destruction of her mother’s portrait – with the Stepmother ripping apart the image and flouncing through the frame. Cinderella is consoled by the arrival of a beaky fairy godmother (retired Principal Artist Lynette Wills) who looks more Nanny McPhee than ‘Bibbity-bobbity-boo’ with her demure grey coat, bowler hat and spectacles. The magic she weaves is as much memory as anything else, as the image of Cinderella’s mother appears, projected across every surface of the room.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

The reference to Nanny is apt here, although on further reflection, Ratmansky’s take on the fairy godmother bears some similarities to P.L Travers’ Mary Poppins, whisking her charges to paste the golden stars onto the night sky. Cinderella’s Fairy Godmother whisks her up above the earth where planets, stars, the sun and the moon dance above the clouds.

Truthfully, had Ratmansky’s choreography been less interesting, we might have had more time to ruminate on the cheek of dressing lithe, fit, ballet dancers in what are essentially textured beach balls at hip level. Mercury’s (Chengwu Guo) costume is particularly outlandish – a swishy skirt made like cheerleading pom-poms, a winged hat and a golden breastplate. Nevertheless, what should be a fashion disaster manages to come across as incredibly chic – a fantastical take on the solar system and the dance between the sun and the moon made possible by a designer willing to take the risk. This section replaces Frederick Ashton’s dance for the Four Seasons; Winter, Spring and Summer fairies replaced by celestial bodies. It is a wise move, for it sets Ratmansky’s version apart for older Australian audiences, some of whom may still remember Sir Robert Helpmann and Ashton himself performing as the ugly stepsisters in Ashton’s Cinderella in 1972.

© Jerome Kaplan. (Click image for larger version)

At the ball, Ratmansky’s choreography certainly taps into the craze for social dancing between the wars – this is a party, after all, but one in which loose, undulating steps bleed into circular lifts and sharp arabesques. There is the conga line of hip isolations and jazz hands, as well as busy, prancing steps en pointe and partnering work that sees the female dancers tilted backwards and slid around the stage by their partners, rather like elegant, satin-clad wheelbarrows in slim suits and pincurls. The arrival of Cinderella in her tea-length gown inspires a fashion overhaul, with satin leisure suits traded for gowns. This interwar era comes alive again through digital magic, as the moon melts into a Dali-esque clock at midnight, when rows of garden topiaries are transformed into enormous ticking metronomes with all-seeing eyes across the faces, or even, in a kind of retro throwback to Walt Disney, a projection of a cartoonish ship that sails by in the background as the Prince travels the world, searching for his lost love.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

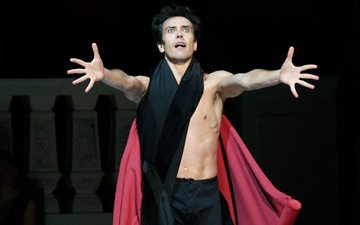

As the Prince, Daniel Gaudiello is excellent. The casting for this ballet was announced quite late, with Ratmansky delaying the final decisions. However, this is a choreographer who knows what he is doing with casting as much as anything else. Interestingly, the last time Ratmansky worked with the Australian Ballet (in 2009 to create Scuolo di Ballo) he paired Gaudiello and Stojmenov. Gaudiello’s deep plie and soaring jump suit the choreography which eats up the space in quick, complex pathways. Above all, however, Gaudiello is believable in the role, tossing his hair and swaggering across the stage in his shiny white suit.

The ballet ends just as it should, with Cinderella discovered and the Stepmother and Stepsisters whisked off in suitable, slapstick style. Cinderella is reunited with a repaired painting of her mother as the Fairy Godmother slips unobtrusively away, tucking the silver slipper into her coat.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

If this production has one main theme it is that more is better: larger gestures, deeper backbends, and more magnified emotional states elevate the possibilities for a large-scale fairytale work of this ilk. The artistic choices, both in terms of choreography and aesthetics, are layered and textured. The set features full length walls of fringe and frothing silk, moveable set pieces including an oversized pink sofa in the shape of puckered lips, and glossy projections (designed by Wendall K. Harrington) that alternately transform the face of the moon into a clock, create the sensation of falling stars, or cast a golden glow to indicate the transition from real life into one of Cinderella’s hopeful fantasies. A similar effect happens choreographically, with Ratmansky drawing from a number of different movement traditions.

When the Australian Ballet takes Cinderella to Sydney later in the year, Bolshoi/American Ballet Theatre artist David Hallberg will perform with the company. Sydneysiders are lucky to have a chance to see him in the role of the Prince although at the end of the day, I feel lucky just to have seen the premiere and to have been genuinely delighted by its wonder.

Wonderful, evocative review. And how I’d love to see this new Cinderella!

Thanks Marina! Hopefully you get a chance to see it at some point- it is really a lovely production.