© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The Royal Ballet

Chroma, The Human Seasons, The Rite of Spring

London, Royal Opera House

9 November 2013

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

www.roh.org.uk

The Royal Ballet’s autumn season triple bill offered very different ways of presenting bodies in space: anatomical studies in an architectural limbo (Chroma); flying figures in constant flux (The Human Seasons); a tribal community following ritual patterns (The Rite of Spring).

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Wayne McGregor’s Chroma (2006), which resulted in his appointment as resident choreographer, was startling at the time because of the unballetic extremes to which he stretched dancers’ bodies. Since then, his choreographic contortions have become familiar and rather less challenging. His striving to find an alternative vocabulary to neo-classical ballet has its limitations, so over the years he has gradually absorbed more established (and safer) ways of using the dancers’ training.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

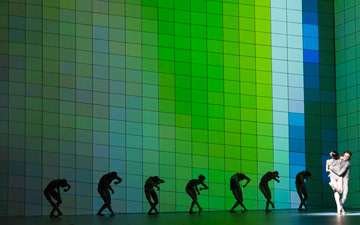

Chroma requires hyper-flexible physiques for its series of duets, in which men seem prepared to wrench their female partner’s legs out of their sockets. The splayed positions and undulating spines, arched lower backs and jutting pelvises imply emotional tension, even sado-masochism, but at the end of each coupling, the participants simply walk away from each other: nothing meaningful has taken place. Spectators stand impassively by in John Pawson’s stark set, their upright forms contrasting with the calligraphic squiggles of their fellows in action. Skimpy costumes are designed (by Moritz Junge) to match the ten performers’ skin tones, which, with the exception of dark Eric Underwood, are shades of deathly pale.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The music, a combination of orchestral racket and plangent piano by Joby Talbot and Jack White, bears little relation to what’s going on until Steven McRae brings out its jazzy rhythms in his solo spot, like the tap dancer he is. A big finale aims to convince the audience that the convoluted encounters have added up to a ballet. Not really. Chroma resists interpretation other than as a cool showcase for acrobatic bodies.

David Dawson’s new work, The Human Seasons, is his first commission from the Royal Ballet. After starting his career as a dancer in British companies, he has made his name as choreographer elsewhere. English National Ballet has performed two of his works, A Million Kisses to My Skin and Faun(e), which raised expectations of his talent as a ballet-based creator. Indeed, it’s a relief at first to see eight of Chroma’s cast of ten reappearing without distortions to their classical line, using recognisable steps to make the most of the stage space. But then the steps give way to running and running – a sign, like Chroma’s walking, of a choreographer’s flagging invention.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Dawson’s inspiration is the Keats sonnet comparing the ages of man to the seasons of the year. The commissioned music is by British composer Greg Haines, who sounds as if he had Mahler and Philip Glass in mind: lots of ecstatic strings, chiming chords and pulsing repetitions. The stark set, by Enzo Henze, has enclosed side walls and a dark backdrop against which white laser beams are projected.

The seasons aren’t readily distinguished, though obviously the ballet starts with ‘lusty Spring’. Steven McRae has a dynamic solo, joined by three young women, Olivia Cowley, Itziar Mendizabal and Beatriz Stix-Brunell, in dark blue leotards. Maybe they’re three Fates, maybe not. Edward Watson is then joined by Lauren Cuthbertson for a pas de deux with high-flying lifts. It’s the first of many such duets, all on the move, swirling and swooping. Some of the lifts are rapturous, others almost as grotesque as MacGregor’s couplings; particularly demeaning is a sweeping manouevre in which a woman is dragged along the floor by one leg, face down, as though she’s being used to mop the stage. Why?

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Since all seven women are identically dressed, I had a problem identifying them. Blonde Melissa Hamilton has gone dark so as not to be taken for Sarah Lamb, but can now be confused with Cuthbertson or Marianela Nunez (also darker than before). Dawson’s choreography, with its free-flowing arms and torsoes and frequent outward circling of the legs (renversés en dehors) doesn’t reveal the sequence of seasons, in spite of pauses in silence that punctuate the flux.

Perhaps we’ve reached autumn when Hamilton is mass-partnered by six men as if she’s a leaf on the wind. Skeins of women stream in diagonals across the space. There’s time for fast-moving solos by Federico Bonelli, Watson and McRae – again – interspersed with running about to change places or make rapid exits.

© Dave Morgan, by kind permission of the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The last two lines of Keats’ sonnet equate winter with mortality. Sure enough, Bonelli crosses the stage to doomed music, yearning arm raised aloft as he seeks wilting Nunez. A Messenger of Death lurks in the background, joined by a quartet in flying angel lifts. What a disappointment: Dawson has resorted to balletic clichés, including ending with the ‘Présages’ lifts (women held above the men’s heads, one leg straight, the other bent) with which he opened the piece. Ah well, seasons return, individuals die, life goes on.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The tribe in Kenneth MacMillan’s Rite of Spring believes that spring won’t return unless a life is sacrificed. Stephanie Jordan has contributed a fascinating programme note about the many different accounts of Stravinsky’s score in the century since it was first performed. MacMillan’s 1962 Rite, the most familiar to Royal Ballet audiences, alters its impact with the choice of sacrificial victim. Zenaida Yanowsky accepts her fate, like a suicide ‘martyr’, instead of flailing frantically to the end. She submits in a trance, exalted as the embodiment of her people’s collective will. Her death is less shocking as a result – or have we become desensitised to martyrdom?

© Dave Morgan, by kind permission of the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

You must be logged in to post a comment.