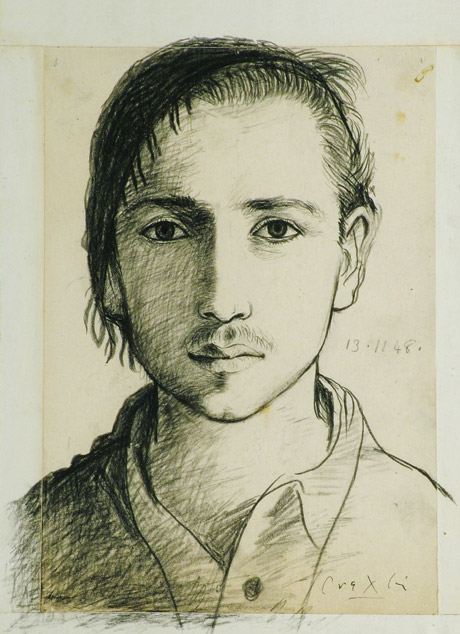

Photograph by Matthew Thomas, © estate of John Craxton.

A world of private mystery: John Craxton RA (1922 – 2009)

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Until 21 April 2014

www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

John Craxton is known – if at all – for his book jackets for Patrick Leigh Fermor’s travel writings and as the designer of Frederick Ashton’s Daphnis and Chloë, whose story he likened to a Pompeian Barbara Cartland. Hiding in that remark is Craxton’s sideways appreciation of life that the Fitzwilliam museum’s exhibition only fitfully reveals. Craxton claimed that to be successful a painting must be enigmatic. Despite an impressive retrospective – presenting works from the 1940s to 2003 – Craxton the man remains an enigma.

© Estate of John Craxton.

Craxton himself resisted labels. Influences on his work are eclectic – English romanticism, Picasso and cubism, William Blake, the Mediterranean light of his spiritual home on Crete – yet Craxton’s style is distinctly his own. He displays a mastery of colour and line that is equally articulate in landscapes, still lifes, figurative compositions and portraits. Only in a portrait of a friends’ baby is there a sense of Craxton fulfilling a commission. Otherwise he was very much a free spirit.

© Estate of John Craxton.

That freedom of expression was unlocked by Craxton’s travels around the Greek islands. He literally went AWOL, presumed missing. The painting that resulted, Pastoral for PW from 1948, contains many recurring images in Craxton’s work, goats, stylised craggy rock formations and trees, a carelessly attractive young man, striking contrasts of light. It is a distinctively confident painting.

The exhibition begins in 1941 with the young Craxton, rejected for military service, attempting to find a voice and justify the role of the artist in wartime. Poet in a landscape is a deliberate echo of Samuel Palmer’s similar, bucolic composition from 1825 – but Craxton’s angry landscape is wracked with splintered trees and vegetation gone to seed.

© Estate of John Craxton.

Nor are his other early experiments with landscapes conventional. The billowing chestnut trees in Cart track, from 1942, have a cactus-like spikiness, and are rendered in exotically intense greens. Craxton was working in household enamel paints due to wartime shortages and the vibrancy of the colours hints at his later work in Greece.

Of these, Landscape with the elements from the 1970s is the design for a tapestry, dynamic in its interplay of colour and nature. A radiating orange sun pierces the waves of a green sea and splashing fish. A landscape depicting Hydra from a decade earlier is a study in fragmented shapes and lines – turquoises, blues, vivid greens – inspired by Craxton’s interest in Byzantine mosaics.

© Estate of John Craxton.

Craxton’s mastery of line is also evident in Still life with cat and child. A lobster, octopus and squid are the tantalising attraction for a hungry cat, all rendered with a freshness and clarity in a few coloured lines of red, orange, blue and green. Cats repeatedly reveal Craxton’s sense of humour – in a cartoon for a Christmas card, Ten puss fugit, and in Cretan cats where, felinely curled around a wooden chair, two cats fight for the possession of a fish bone. That painting dates from 2003 but Craxton went on working after that, overseeing the return of his designs for Daphnis and Chloë for The Royal Ballet the following year. Dismissed originally as contemporary beachwear his costumes and sets now have classic status.

Suzanne Hickinbotham, from the production department of the Royal Opera House, told me, “Craxton didn’t like, didn’t believe that the original designs were his when he saw them. He still didn’t like them when a set model was made. So he redesigned. He was always allowed to fiddle. He changed the silhouette of the mountains and was very concerned to get the correct blue on the borders and on the back cloth. Craxton did lots of the painting himself, working from a wheelie-chair.”

The exhibition makes nothing of Daphnis and Chloë. Closest we get is Galatas from 1947 and a vine-covered pergola that later reappeared in the first scene of the ballet. There is an unexplained autographed photograph of Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev with Craxton. A radiant Fonteyn, pictured on holiday in Greece with the artist at the time of Daphnis, incidentally decorates the exit door of the exhibition. Ashton commissioned Craxton to redesign Apollo – a ballet for which he would appear ideally suited. The results did not find favour with the guardians of George Balanchine’s work – but frustratingly we get to see nothing of that.

© Bill Cooper.

Dancing is represented by shepherds, sailors and other young men, another of Craxton’s recurring motifs. In Three dancers – Poros you feel the pulse of dance in the interplay of blue and ochre. There is an enigmatic quality in Craxton’s depiction of men. Shepherd and rocks reveals a lone figure lost in thought, tender and remote. In Still life with three sailors the toughness of male camaraderie is hinted at in this scene of fish and chips, drinking and smoking, but there is a vulnerability about Craxton’s sailors and soldiers, in paintings not exhibited here, that exposes the human being beneath the uniform.

© Estate of John Craxton.

Craxton said, “I love sailors and hate navies, love soldiers, hate armies.” That humanity is seen in Reclining figure with asphodels I. A young sailor sleeps among asphodels – which Craxton identified as the location in the afterlife reserved for ordinary folk, whose company he preferred. It is a beautifully serene image.

The exhibition adds nothing of note to the literature about Craxton. The Fitzwilliam has produced a slim volume, more a brochure than a catalogue, and recommends the 2011 book by Ian Collins published by Lund Humphries. That volume was compiled with Craxton’s reluctant cooperation and is, as Collins admits, far from definitive. It is also marred by reproductions that muddy Craxton’s vibrant use of colour.

© Estate of John Craxton.

Sparkle, ping and twang are words repeated by David Attenborough to describe Craxton’s palette in a BBC film about Tate Britain’s recent, smaller, Craxton exhibition. A friend of Craxton, Attenborough is a genuine enthusiast but his perspectives are not profound. Nor, screened in a corridor between a lift and staircase, do the Fitzwilliam present the film in conducive surroundings. And could not the Fitzwilliam have found a way of screening Daphnis and Chloë too?

Craxton’s world is tantalisingly private in this exhibition – but do go and

You must be logged in to post a comment.