© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

KAGE Physical Theatre

Forklift

Melbourne, Arts Centre

www.kage.com.au

www.artscentremelbourne.com.au

To the side of the seating bank looms the gray stonewall of the National Gallery of Victoria, decorated for the summer season with splashy advertisements for the latest contemporary installation, Melbourne Now. Straight ahead, past the makeshift stage of a paved courtyard and stacked pallets of cardboard boxes, rests the concrete and glass magnificence of the Arts Centre. Above, the Arts Centre’s distinctive spire, reportedly modeled on the folds of a ballerina’s tutu mid-twirl, stretches high into the sky. This is the setting for Forklift, the latest premiere from Melbourne-based KAGE Physical Theatre. Directed by the ‘KA’ of KAGE, Kate Denborough, Forklift features three women and (ok, not a surprise)… a forklift. This is an urban rather than an industrial landscape, with the clangs and creaks of trams and the chatting of passing pedestrians adding to Jethro Woodward’s original sound composition.

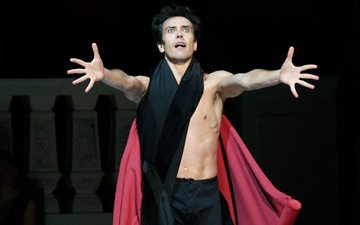

Forklift begins with a gag. A woman, Nicci Wilks, sporting an oversized neon work jacket wanders in with her esky and thermos, calling instructions to the technicians at the lighting board. Her character is grounded in the caveman, gum-chewing, bum-scratching stereotype of construction workers. After a quick snack, she climbs in her forklift, and disappears offstage, only to return with two bodies draped across the machine. These two women, Amy MacPherson and Henna Kaikula, are dressed in the drab brown colour of cardboard, but act as sirens, seducing both the machine and its original driver from their most pragmatic purpose.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

The forklift is a surprisingly versatile prop. The performers hang from its metal prongs, climb along the roof, contort across its lift, and shimmy down the sides to slip behind the wheel. The forklift rarely stops moving. It weaves back and forth across the stage, spins in place and performs many tricks, including raising and tipping its metal prongs. This is probably more dangerous than your average circus performance, and certainly more risky than the kind of contemporary physical theatre KAGE usually offers. The forklift raises the performers high in the air where they perform acrobatics on a flying pallet, yet the floor beneath the performers is unsympathetic brick paving. Fortunately, all three performers and their director are licensed forklift operators; and in case there is any residual confusion, KAGE’s website reminds its audience, “Forklifts are not to be used like this in the workplace.”

Lighting is designed by local collective, Bluebottle, which is renowned for its stand-out concepts. However, during the premiere performance (which took place outside at 6:30pm), the lighting design was rendered invisible under the wash of daylight. This was an error on the part of KAGE and its producers; we missed the direction and atmosphere that comes with a lighting concept: the nuances of moving muscles in silhouette, the play of shadows against a wall, and crucially for Forklift, the glow-in-the-dark reflections of the high-visibility materials. Compared to the production pics and online videos, it seems that Melbourne audiences got a much less vibrant and significantly less visually-directed, experience.

In hindsight, I wonder if the absence of theatrical lighting actually highlighted the slow and often meditative tempo of Forklift, as well as the sense of disappointment that came with an ending rather than a resolution. But it may also be the function of a work that draws from a number of different inspirations and structures. Here, Denborough has retained clear circus acts, but developed the transitions into performative events of their own, effectively equalising the big acts and the material between them. The choice to blend the edges of sequences allows the work to slip in and out of focus, particularly as Forklift is rarely ever lively. It is occasionally funny, but the humour is downplayed, as are the peaks and troughs of a kind of emotional journey.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

Despite any issues it may have with finding dynamical variations, Forklift is littered with theatrical gems. At one stage, a performer fetches a can of Sprite from a vending machine and shares it with her colleagues. The Sprite is left, seemingly forgotten, on the roof of the machine- right between two balancing pegs. Although it seems impossible for it to stay upright against a tide of swinging legs and arms, not a drop is spilt. At another moment, Wilks lounges behind the wheel, flipping through a pornographic magazine. In a brilliant bit of cheek towards the man’s world of the construction industry, it is a naked man, rather than a busty blonde, whose image captures her attention. Denborough continues this nod towards gender stereotypes later, when all three women pull on leotards decorated with high-vis neon panels. These glowing, shimmering interpretations of ‘work-wear’ demonstrate the way in which Forklift makes beautiful that which is usually just functional: the colours of high-visibility become a cheerful neon pallet, the forklift becomes a toy for the performers to play with.

Although it might be convenient to classify the ‘forklift’ (it gets its own curtain call at the end) as a fourth performer onstage, the truth is that the machine remains a prop throughout. This is because the act of driving it is made so visible. All three performers take turns operating the forklift, and the way in which the women perform a continuous swapping of seats, shifting of gears, and cranking of breaks continually reminds us that the forklift is something to be manipulated. It becomes an extension of the performers’ desires- to spin, to perch high in the air, or to transport bodies from one resting place to the next.

KAGE, a partnership between Denborough and Gerard van Dyck, has been presenting work for fifteen years, and their creativity shows no sign of abating. Although Forklift has some issues, it still stands as a strong piece of theatre: unique, creative, and entertaining.

You must be logged in to post a comment.