© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

A La Francaise: Acheron, Afternoon of a Faun, Walpurgisnacht Ballet, La Valse

New York, David H. Koch Theater

21 February 2014

www.nycballet.com

Suite Française

George Balanchine’s favorite composers may have been Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky, but it’s no secret that he also had an affinity for France and its music. His admiration for Gallic charm pours forth in ballets like Emeralds, Le Tombeau de Couperin, and La Source. He also had a great admiration for certain French ballerinas, particularly Violette Verdy, for whom he created a string of sparkling roles. Paris was the scene of some of his earliest successes, including Apollo and Prodigal Son, both created for the Ballets Russes. In fact, after the death of Serge Diaghilev (and the dissolution of his company), Balanchine had hopes that he might be offered a job at the Paris Opéra. (Instead, the post went to the dancer Serge Lifar.) But Balanchine returned periodically. In 1947 he directed the Opéra for six months, leaving behind, as a gift, the ballet Le Palais de Cristal (later renamed Symphony in C), set to the music of Bizet.

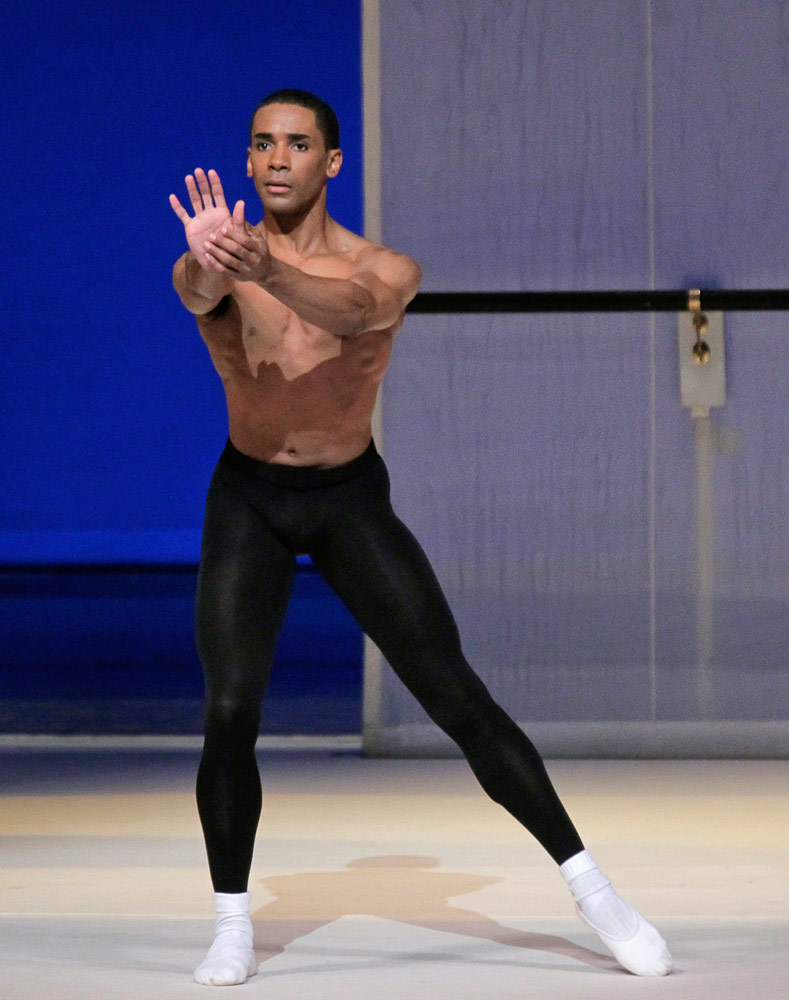

All this comes to mind as New York City Ballet presents a strong French program made up of works by Balanchine, Jerome Robbins, and the young Briton Liam Scarlett (replacing a delayed première by Peter Martins). The four ballets – Acheron, Afternoon of a Faun, Walpurgisnacht Ballet, and La Valse – are different enough to provide welcome contrast, but have in common a theatricality and sense of style that sets them apart from the rest of the repertory. The revelation of the evening was Afternoon of a Faun, danced here by Sterling Hyltin and Craig Hall. Both have performed it before, but there was something bracingly fresh in their approach, a sense of surprise that peeled away at the ballet’s dewy atmosphere.

Robbins’ ballet is set in a rehearsal studio in which a young ballerina comes upon a male dancer in the midst of an afternoon reverie. She enters on tiptoe, fiddles with her tunic, stretches her legs, and then bends forward languidly, her hair spilling over her torso. Then, as she looks up, she catches the man’s gaze in the mirror. Hyltin imbues this moment with a stillness that conveys a mix of curiosity and fear. Her reaction is almost like that of an animal sniffing the air, ready to dart off at the slightest danger. There is none of the mawkishness that often lingers over the proceedings. Her exquisitely light carriage and nervous energy give her a truly nymph-like air, as if she were half human, half creature of the forest.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Hall, too, makes the most of the ballet’s conceit, which is that the fourth wall – in other words, the audience – is in fact the mirror of the ballet studio. He embraces the narcissism that is built into the role, unwilling to pull his eyes away from his own reflection even for an instant. There is no illusion of innocence, and this is somehow refreshing. Hall also handles Hyltin with great deftness, making the ballet’s sudden, magical lifts appear almost involuntary. The nine-minute ballet registers like a delicious, pagan dream.

It is eerie to think that two of the works on the program (Afternoon of a Faun and La Valse) were created for the ballerina Tanaquil LeClercq, Balanchine’s third wife, struck with Polio at the age of twenty-seven, and now the subject of a moving documentary, Afternoon of a Faun. LeClercq’s dramatic intelligence, sense of chic, and air of knowingness – she was half-French, born in Paris – hover over the evening. These very qualities are the subject of La Valse, a whirling vortex of a ballet set to Ravel’s Valses Nobles et Sentimentales and La Valse, music composed on the eve of the First World War. Ravel’s music captures the madness of the age, the feeling of, as he put it, “dancing on the edge of a volcano.”

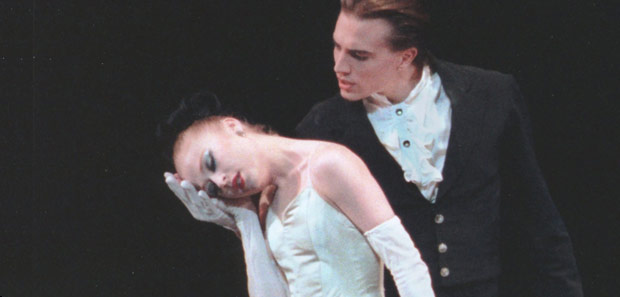

Similarly, Balanchine’s ballet is like a fever dream, enticing, fascinating, and slightly toxic. Karinska’s costumes, made of multilayered purple-and-crimson tulle with glistening black bodices accessorized with long white gloves, accentuate the extreme mannerism of the choreography. Women hold their hands to their heads melodramatically and strike Vogue covergirl poses, flick their wrists, extend their fingers until they become vaguely claw-like.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

The central couple, danced here by Janie Taylor and Sébastien Marcovici – both retiring at the end of the season – capture this febrile quality, especially Taylor, who throws herself at her partner with almost frightening avidity. Marcovici uses his somewhat remote quality to maximum effect. He’s too pallid, too stylized to hold Taylor’s attention. Taylor is doomed from the start, hungry for danger and excitement. And that’s what she gets with the arrival of the death character (Amar Ramasar). He appears suddenly behind a black curtain, like a tantalizing vision. The action freezes, as if the ballroom had been put under a spell (as in Sleeping Beauty). Only she can see him. Like an addict in search of a fix, she dives in, fear quickly replaced by an all-consuming appetite. As the ballet ends the dancing continues in a blind whorl around her limp body. The dénouement is not unexpected, but still the ballet draws you into its topsy-turvy crescendo, flying tulle and all.

At this performance the three supporting couples, representing different categories of social interaction – obliviously light-hearted, manipulative, or domineering – were also excellently danced. Lauren King showed a new freedom in her upper body; Ashley Laracey was convincingly coy one moment, cruel the next.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

I’ve written about Liam Scarlett’s Acheron elsewhere. On repeated viewing it continues to cast its gloomy spell. Heavy-handed, oppressive partnering is used to imply something rather sinister about the relations between men and women. The dancers’ grappling becomes a tug-of-war of aggression and sensual acquiescence. Similarly, the music, Poulenc’s Concerto in G for Organ, Strings, and Timpani, alternates between reverberant exclamations for the organ and insinuating melodies for the strings. The most haunting image is of two women (Sara Mearns and Megan Fairchild) slowly advancing in tandem as if swimming through glue, then being pulled rather violently into the shadows by their partners. It’s more than a little claustrophobic – the whole ballet feels airless. It is also notably adult, a nightmare vision of co-dependency.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Walpurgisnacht Ballet, set to ballet music from Gounod’s Faust, is the opposite, a youthful piece – originally created to complement a Paris Opéra production – that seems concerned mainly with the corralling of energy. The women – and they are all women, with one exception – surge across the stage, hair and arms flying, creating dynamic patterns, eddies and waves. The music, meant to evoke a night of revelry, is wild and bombastic and completely over-the-top. Which is just as it should be. It’s a storm, à la française.

The French program will be repeated Feb. 26 and March 1.

You must be logged in to post a comment.