© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

Vespro, Spectral Evidence, Acheron

New York, David H. Koch Theater

31 January 2014

www.nycballet.com

About a Boy

On the evening of January 31, New York City Ballet got its first taste of Liam Scarlett, a young British choreographer who, at twenty-seven, is the Royal Ballet’s first Artist in Residence. (The company also has a choreographer-in-residence, Wayne McGregor and Christopher Wheeldon is listed as an Artistic Associate.) Scarlett has already made works for the Miami City Ballet and the Norwegian National Ballet; one of his pas de deux, Fratres, was performed at Fall for Dance last year. The première of Acheron, a new, large-scale ballet, revealed a choreographer of prodigious imagination and compositional craft, adept at building an atmosphere and suffusing it with traces of meaning. Though the ballet is abstract, without characters or a plot, an underlying theme coalesces by the end. With this deeper understanding, everything that comes before is bathed in a different hue. I’m eager to see it again, armed with this knowledge.

As Scarlett, a former Royal Ballet dancer, told the writer Laura Cappelle for the program essay, he is steeped in English ballet history. But it perhaps goes wider and the influence of Kenneth MacMillan, Jiri Kylian, and the Jerome Robbins of Opus 19/The Dreamer is clear. Even more, one senses traces of Christopher Wheeldon’s style, particularly in the elongated, legato line. (Though, on the evidence of this ballet, it seems that his emotional palette is darker.) From the striking first tableau, in which the cast of seventeen advances slowly, backs turned away from the audience and arms held out like supple wings, the atmosphere is mysterious, even dream-like. A solitary figure at the back of he stage, Rebecca Krohn, faces forward, quietly watching the others. Who are these people, drifting like lost souls? Later, almost halfway through the ballet, the diminutive, lithe, and exquisitely precise Anthony Huxley appears, flickering through the currents. He barely seems to touch the ground. As the others pair off and engage in turbulent, intimate encounters, he watches, slightly removed, like a boy on the verge of adulthood, fascinated and slightly frightened by the behavior of the adults around him.

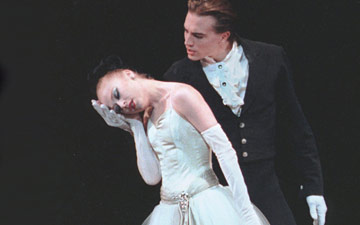

The ballet is dominated by heterosexual couples, a fact that seems relevant because it suggests that the boy’s apprehension might be motivated by feelings of isolation and otherness. We see them through his eyes. The couples’ interactions are sensual, oppressively so. The men, who are shirtless – their knee-length tights and the pretty, pale blue dresses for the women, were designed by Scarlett – dominate the women, in subtle and not so subtle ways. They caress their bare arms, shoulders, necks, pulling them backward into swoons. (One can almost feel the gooseflesh.) The women sometimes resist, pushing back, freeing themselves momentarily from their grasp. Slowly, surely, the men break down their resistance. At the end of one pas de deux, for Ashley Bouder and Amar Ramasar, the dancers are on the floor, their bodies twined so tightly that one is indistinguishable from the other. The image is airless, claustrophobic.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Not surprisingly, the choreography is filled with knotty partnering and an endless variety of lifts, some of which are still being ironed out by the dancers, though, for the most part, they performed with admirable fluidity. In one of these, Tyler Angle kisses the sinuous curve of Rebecca Krohn’s neck, then, without warning, lifts her up, upside down and with her legs crossed, like an exotic prey. The effect is slightly shocking. Krohn, only recently promoted to principal, is a very beautiful woman, and a dancer with a melancholy and slightly passive air. She’s like a sleeping princess waiting to be woken. This quality works well in roles like the Girl in Mauve in Robbins’ Dances at a Gathering, but less so in Balanchine ballets, which demand a stronger point of view. In Acheron, Scarlett has exploited Krohn’s languid beauty to reveal a dark sensuality beneath the placid porcelain surface. It will be intriguing to see how this discovery affects her approach to other roles.

The choreographer has chosen dancers with a particularly lush legato quality, pliant torsos, and soft port de bras. Sara Mearns is an obvious choice, as is the lithe (and intense) Adrian Danchig-Waring, her partner. (Perhaps in Mearns’ honor, Scarlett seems to have dropped in a reference to the adagio movement of Balanchine’s Symphony in C, in which the ballerina swoons to one side and then the other, over and over, a long sequence that feels as if it were executed on a single breath.) Tyler Angle, the company’s most ardent partner, is suitably romantic, and brawny. Ashley Bouder, despite her reputation as a brilliant technician who sometimes goes for the hard sell, here deploys her upper body with suppleness and elegance. But Scarlett has also taken note of her indomitable strength, giving her a very “Bouder” step in which she pauses on pointe for an extra beat, to mark a fermata in the music. Scarlett not only shapes the dancers to his needs, but recognizes and uses their individual strengths.

One of the most remarkable aspects of his style is the elasticity of the phrasing, how one movement flows powerfully into the next, with weight and effort. The torso twists, the knees bend, the head completes the shape. It’s heartening to see these dancers use their upper bodies and arms so opulently, a quality sometimes lacking when they dance works like Symphony in C or, more recently, Diamonds. Scarlett slows them down and reveals new facets, beyond speed and clarity. At times they look like they’re moving through water.

The choreography for the ensemble is satisfyingly complex, with touches of counterpoint and layering; motifs echo across the stage. There is a striking double pas de deux in which each couple responds to a different voice in the orchestra. The music is Poulenc’s Concerto in G for Organ, Strings, and Tympani. With its blaring organ alternating with soaring or weeping strings, it provides a melodramatic and portentous backdrop. (Glen Tetley used the concerto in his equally portentous 1973 ballet Voluntaries.) Scarlett has an affinity for Poulenc, whose music he also used for his breakthrough work for the Royal Ballet, Asphodel Meadows. He manages to exploit its emotional dynamics without coming across as histrionic, quite a feat. By now it is clear he also has an affinity for obscure titles. In case you were wondering, Acheron is a river in Greek mythology known as the river of woe, which seems appropriate.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Scarlett’s ballet was performed on a mixed bill of contemporary works, alongside Mauro Bigonzetti’s Vespro and Angelin Preljocaj’s Spectral Evidence. I’ve written about those two ballets before, so I won’t bore you again here. Suffice it to say that on second viewing, Vespro looks even more clumsy and heavy-handed – a generic study in crepuscular angst – than it did last season, despite a committed performance from the entire cast, and in particular Andrew Veyette. Spectral Evidence is a more intriguing piece – a creepy and stylish reverie on sexual repression and ghostly seduction. The men are buttoned-up clergy; the women, comely witches in bloodied shifts. The imagery – banging fists, grotesque mime, white, coffin-like boxes that turn into walls and pyres – is striking, but the ballet goes on for too long and the novelty wears off well before the end. But at least it’s original. With Acheron, though, the company gets a new work that’s built to last.

You must be logged in to post a comment.