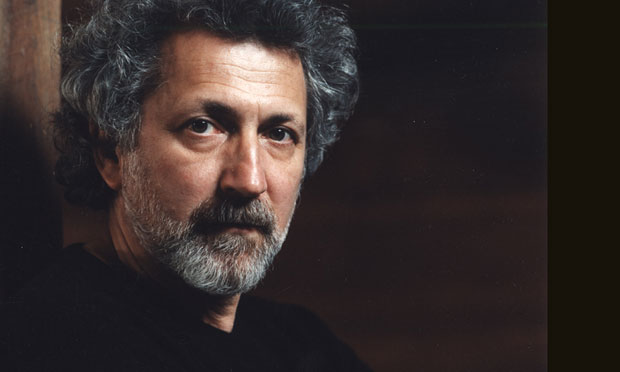

© Eifman Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

Building on Tradition

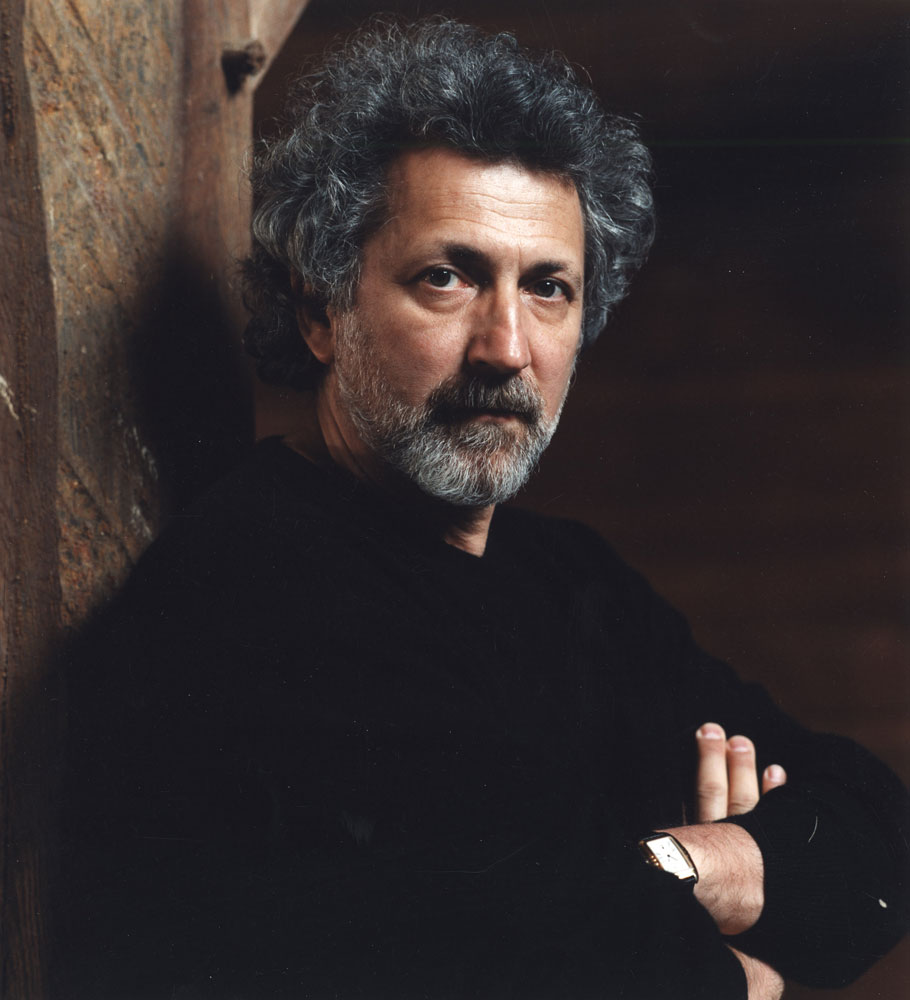

Boris Eifman (tip, pronounce it ay-f-man, not aye-f-man) founded his dance company in 1977. Originally called the Leningrad New Ballet, but now known as the St Petersburg Eifman Ballet, the company has gained a huge following – in Russia and throughout the world – touring internationally on a frequent basis.

In January 2011 the Governor of St Petersburg signed a decree supporting the establishment of the Boris Eifman Dance Academy and, in September 2013, a superb purpose-built complex opened its doors onto Lisa Chaikina Street in St Petersburg to an inaugural intake of 90 students (48 aged 7, and 42 in an older age group at 11/12). The academy – based in a former cinema building dating back to 1913 – comprises no less than 14 dance studios (equipped with digital recording and instant playback facilities), spacious, light accommodation for the students, together with administration, catering, classroom and performance spaces (not to mention much-needed rehearsal space for the Eifman company itself).

Eifman has choreographed more than 40 works and his company, which now numbers around 60 dancers, has a good claim to be the largest contemporary dance ensemble in the world. The Eifman Ballet performs a repertoire of works exclusively made by its founder and director and will bring one of his latest, Rodin (which premiered in St Petersburg in 2011) to the London Coliseum for three performances on the evenings of 15/16/17 April, followed by two performances of Anna Karenina on Saturday, 19 April.

Graham Watts met up with the choreographer on a recent visit to St Petersburg to discuss his career and to ask what London audiences might expect from Rodin. (Graham Watts review of Rodin)

© Souheil Michael Khoury. (Click image for larger version)

GW: You started your company, in 1977, when you were aged 30. What motivated you to start so early?

BE: My first choreography was made when I was just 13 and still at ballet school. By 16, I already had a small company, using some dancers from my class, while others were adults – amateurs, really. They worked elsewhere and came to dance with me because they loved it.

At that time a lot of people were doing this kind of amateur stuff and I just joined in. So, I suppose one could say that I had a company of sorts right back in the early 1960s!

How unusual was it in the Soviet Union for such a young person to be choreographing dance for public performance?

Well, if there were any other examples of teenagers like me then I wasn’t aware of them. What made me different is that I had a clear choreographic vision from an early age.

In fact, what I believed in when I was 15 or 16 – what I imagined at that age – I still stick to today. Even back then, I would often base my concepts on pieces of literature and cinema and would produce choreography with an elaborated storyline. So I could say that my penchant for drama in ballet dates back to my earliest memories. I might even say that it is genetic.

Who were the most profound influences on your emergence as a choreographer?

To begin with, I would have to say Leonid Jacobson, whom I first met when I was 15. Already, at that age, I was very interested in what he was doing, especially his approach to improvisation. I particularly recall asking him how he became a choreographer and his memorable reply was: “you don’t become a choreographer; you have to be born one”.

In 1975, Jacobson and I were working together, preparing an evening at the Kirov Ballet in St Petersburg to celebrate the career of Gabriella Komleva (a leading Kirov ballerina from 1957 until her retirement in 1988). It was actually the last piece that Jacobson choreographed. He had cancer and he was aware that he did not have long left to live (he died in October 1975). For me, it was the first time that I had worked in the Kirov Theatre (now, of course, back to its original name as the Mariinsky).

© Stanislav Belyaevs. (Click image for larger version)

Jacobson was choreographing The Firebird and I was helping him. There was a discussion about the production and Jacobson said that he believed that “Eifman could be his successor”. I still feel the responsibility of inheriting that legacy, even now.

Jacobson was very important to my development but I was also greatly influenced by (Yuri) Grigorovich. Their work is so different that I feel now that each contributed something separate and indelible to my skills as a choreographer.

Grigorovich is all about constructing a large drama piece and Jacobson produced an outflow of fantasy. For him, it was very hard to put together a large production. Things would fall apart if it was too big. Jacobson could mastermind miniature pieces and he could work with narratives but only on a smaller scale. Grigorovich was quite the opposite.

I’m happy in having been influenced by both. I absorbed the essence of fantasy and improvisation from Jacobson while at the same time realising – from Grigorovich- the importance of robust construction to bring large-scale pieces to the stage.

Were you aware of what choreographers were doing outside the Soviet Union?

Companies would visit from time-to-time but these were rare occasions. When they came, it opened me up to new opportunities and ideas. One can argue that Russia is still behind because we were cut off from what was going on elsewhere, isolated in a cultural vacuum for so many decades.

However, I have to say that by the time I saw any choreography from outside the Soviet Union, I was already comfortable with my own work. So I found my style as a choreographer from behind the iron curtain in an encapsulated cultural space.

I don’t copy what is done in the west. I am deeply rooted in the Russian ballet tradition and continue to develop it in my work. I believe that this is one of the assets for us as a company, especially when performing abroad, because we represent what is going on in Russia now, which builds on that tradition. So, although I am making contemporary ballet with modern approaches, I still regard my work as an ongoing part of the Russian ballet tradition.

In the years before perestroika did you have problems with censorship?

Oh, yes! From my very first programme, we had trouble getting access to the public. Before any work could be made publically available you had to go through a set of commissions that would decide whether it was OK. Often, at the first commission performance I would get a “no” and I would have to go through the commissions several times before they would agree to a public showing.

It was not that I wanted to revolutionise things or run against the grain that much. It was just that my thinking – my creative fantasy, if you like – was rather different to the Bolshoi standard at the time. I was an admirer of Grigorovich and paid a lot of respect to what he was doing but my style was rather different and it was not considered to be soviet ballet at that time.

It was difficult. I had to fit into the soviet “ballet shoes” during those early years. You have to either cancel work or be adaptable. I was under a lot of pressure at that time since I would want to choreograph to music and use topics that it was impossible to stage with the Bolshoi Ballet language.

© Eifman Ballet. (Click image for larger version)

So, you had work that was cancelled by the commissions?

Nothing was cancelled. But it was hard to get work approved for a public showing.

A lot of “under-the-carpet” diplomacy was needed in order to get things accepted. There were occasions when a commission would say that “by this date, these changes have to be made” and by the date stipulated I would claim that I had made the changes although, in reality, I hadn’t changed a thing. It sometimes happened that they would then pass the work, saying: “oh yes, now we can see the difference”!

I was always seen as an outsider: a bit of a dissident, even. They would never give me the passport to travel abroad. As I said, there was a lot of pressure and some humiliation as well. Whenever I discussed the possibility of travelling abroad they would always say “well, it can only be one way”, meaning that they expected me to go to the west and not return.

How would you describe an Eifman ballet to someone in Britain who has never seen your work?

You can just call it “Eifman” ballet, since – for me – categorisation isn’t necessary. Some like my work, others don’t, but the essential thing is that there is a clear individual style.

As an example of this problem of categorisation, I would highlight the period during which the critics (although, not the public) were hostile to what I was doing, both here in Russia and also in France. For the French, everything needed to fall into one of two categories – there is Russian classical ballet and Western avant garde – and I don’t fit into either category and so it was hard for them to define my work. It took time for them to learn that this is a different style.

I would also highlight the importance I place on engaging with the public. As a student, I was a big fan of ancient Greek drama and I was particularly keen on the catharsis that Greek tragedy was supposed to produce. I hope that my work can also be cathartic to some people.

I don’t want to create the impression that choreography is not important: of course, it is the language through which I achieve what I strive for. I have always tried to find something new in choreography so that I can grow in that respect as well. But, the most important thing for me is to develop expression through dance technique. So that is what I would claim to be the essence of the Eifman style.

Your work always seems to tell a story. You obviously prefer to work with narrative?

Almost all of my work is based on narrative but not everything! My recent production of Requiem (premiered in St Petersburg on 27 January 2014) is based on Mozart’s Requiem and is therefore rather different. But what I am always looking for – even in an abstract piece – is that there has to be some kind of twist: an intrigue, if you like. This might be a surprising turn in a literary narrative or a fascinating biography of the artist or it could be in the drama of the score.

I’m not looking to simply illustrate a piece of music but to be able to work with the very high emotional impact that music by, say, Shostakovich or Mozart might have. Even if it misses a specific narrative, I believe that it is essential for the choreography to match this profound meaning in the music.

© Souheil Michael Khoury. (Click image for larger version)

You often piece together music to create your own “score” from existing sources. Does the music come first or do you find the music to fit your choreographic ideas?

The concept must come first but the music usually follows before anything else. When I was doing Requiem, then clearly Mozart had to be the beginning.

I’m now working on a ballet of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night and I have whole notebooks full of ideas for the music – taken from early 20th Century American jazz – that might create the style that I want.

It takes me a very long time to think about music that will be right for each piece. It can be quite painful. The concept might begin with a piece of literature or a biography but I have to find a very personal concept of what my production is going to be.

My process is more akin to how a director in cinema or theatre operates, rather than how choreographers traditionally work. Once I have the concept then the music must come next. I listen to thousands of hours of music to match my ideas for the work. My musical training from the conservatoire gives me enough knowledge to knit together a score in this way. So, in Rodin, for example, I produced an amalgam of relevant music (pieces from French Romantic composers of the late nineteenth century) that becomes its own body of music. In Onegin, although I used mostly Tchaikovsky, it also has the twist of Russian rock music from the end of the 20th century.

Your choreography is very tough on the dancers who clearly have a strong work ethic. Do you find it difficult to get classically-trained dancers to adapt to your style?

You’re right. It takes me a great deal of time to find dancers that are able to fit in. It is often the case that dancers see my work and immediately think that they can’t cope with it but as soon as they join the company they always find that it is within their capability.

Our first task is to find the talent. I’m no longer focused on the former Soviet Union in searching for my dancers. Now we are happy to extend our search to find the best artists internationally. I believe that there are plenty of great dancers worldwide that would be happy to try themselves in this repertoire.

With every talented artist that I see in the Bolshoi or the Mariinsky, I always think that I could work with that dancer and that they could work with me. Many of these dancers reach the end of their careers not having had the chance to try different things. Many of them have the right combination of being both a gifted dancer and an expressive, dramatic artist and they need a choreographer who is able to make the best of both capacities.

Your dancers are always performing in the same style. There must be a great advantage in having a company that is just performing your choreography?

There is an advantage in being able to nurture dancers in a repertoire that is both diverse and familiar. For example, the leading pair you saw in Rodin (Oleg Gabyshev in the title role and Lyubov Andreyeva as Camille Claudel) have changed so much in the time that they have been here. They have really had to adapt and grow in the company

© Souheil Michael Khoury. (Click image for larger version)

When were you first inspired to make a work about Rodin and how long did it take for the idea to reach the stage?

Sometimes the inspiration is instant and sometimes it takes 10 to 15 years for an idea to lie around in my consciousness before it is the right time to come to fruition. Rodin was one of those ideas that I had been thinking about for awhile.

My work behind the desk, evolving the concept and choosing the music is always the longest period. When I get this preparation right then the choreography usually comes more easily. But, for me to get there I have to do a lot of thinking and a lot of writing, spending half a year behind a desk. In fact, I work here behind the desk more than I do in the studio.

When the concept has been thought through and the music selected, then it takes about 4 months to develop the choreography and work with the dancers. So, I would say that the full-time commitment to create a work such as Rodin is around ten months from concept to stage.

Did the dancers spent time studying Rodin’s life and work in preparation for the ballet?

I find that I don’t really have to educate my dancers. They will instantly become interested themselves and, for example, many went to the Rodin museum in Paris when we were in the city and they viewed every piece of sculpture that they could.

Your dance academy opened this year. If you look forward a few years, what do you hope it will achieve?

I have no difficulty finding dancers that are able to handle the physical side of my choreography. But I need the spiritual and emotional side to coalesce with their development of technique and the idea behind the academy is that I really want to produce a new generation of dancers who are open to dramatic possibilities as well as mastering technique.

I want the graduates of the academy to be able to fulfil the fantasies of the choreographer but also to have the imagination and the fantasy of their own. In essence, I’m looking for dancers who have the capacity to co-author a piece. I believe that there needs to be a lot of work to change the mental outlook of dancers. I want to create dancers who can think for themselves and are not just technically superb performers who can fit into the rigid discipline of someone else’s ideas.

We are hoping that our students will develop diverse cultural baggage through their time at the academy. I want them to read extensively, go to museums, go to the theatre and see and understand design and architecture. It is this holistic artist that we want to create since this breadth of enquiry is, I believe, something that ballet artists are lacking.

Thank you!

You must be logged in to post a comment.