© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Kings of the Dance

Remanso, Le Jeune Homme et la Mort, Les Intermittences du Coeur (from Proust), Prototype, Vestris, Labyrinth of Solitude, KO’d

London, Coliseum

19 March 2014

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

Eric Taub’s review of the Kings in NY (2012)

www.ardani.com

www.eno.org (Coliseum)

Originating in California in 2006, the Kings of the Dance showcase (this being the fifth) features an array of male dancers on leave from world-class ballet companies. Impresarios Sergei Danilian and his wife Gaiane have also presented seven ballerinas in Reflections, as well as two Diana Vishneva tribute programmes. The intended appeal of all these starry productions is the dancer rather than the dance.

Where Ivan Putrov’s Men in Motion tours aim to show how choreographers have been inspired by exceptional male performers, Kings of the Dance is mainly about display. Rather than falling back on the usual gala staples, however, the Kings perform creations suited to their particular talents. There’s evidently a dearth of available choreography for men, since two numbers appeared in both productions at the Coliseum: Leonid Jacobson’s Vestris solo and Roland Petit’s duet from his Proust ballet, Les Intermittences du Coeur.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

These two pieces were in a medley of works making up ‘Act Three’ of the brief evening. ‘Act One’ consisted of Nacho Duato’s Remanso (15 minutes), with two long intervals of 35 minutes each for the mounting and dismounting of the set, borrowed from English National Ballet, for Petit’s Le Jeune Homme et la Mort, the substantial centrepiece.

Remanso is a winsome trio for bare-legged men in tiny shorts and shiny T-shirts, accessorised with a rose, a screen and colourful lighting. The Royal Ballet acquired Remanso at the turn of this century and dropped it in 2002. Nacho Duato, like his mentor Jiri Kylian, combines balletic acrobatics with quirky grotesqueries to amiable music – in this case, Granados’s Poetic Waltzes. Of the three men, impish Leonid Sarafanov, tall Marcelo Gomes and jester-like Denis Matvienko, Sarafanov made the clearest distinctions between turned-out and parallel positions, arched or flexed feet. A fine-drawn dancer, he dissipated his effects by anticipating the (recorded) music, instead of responding to it.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

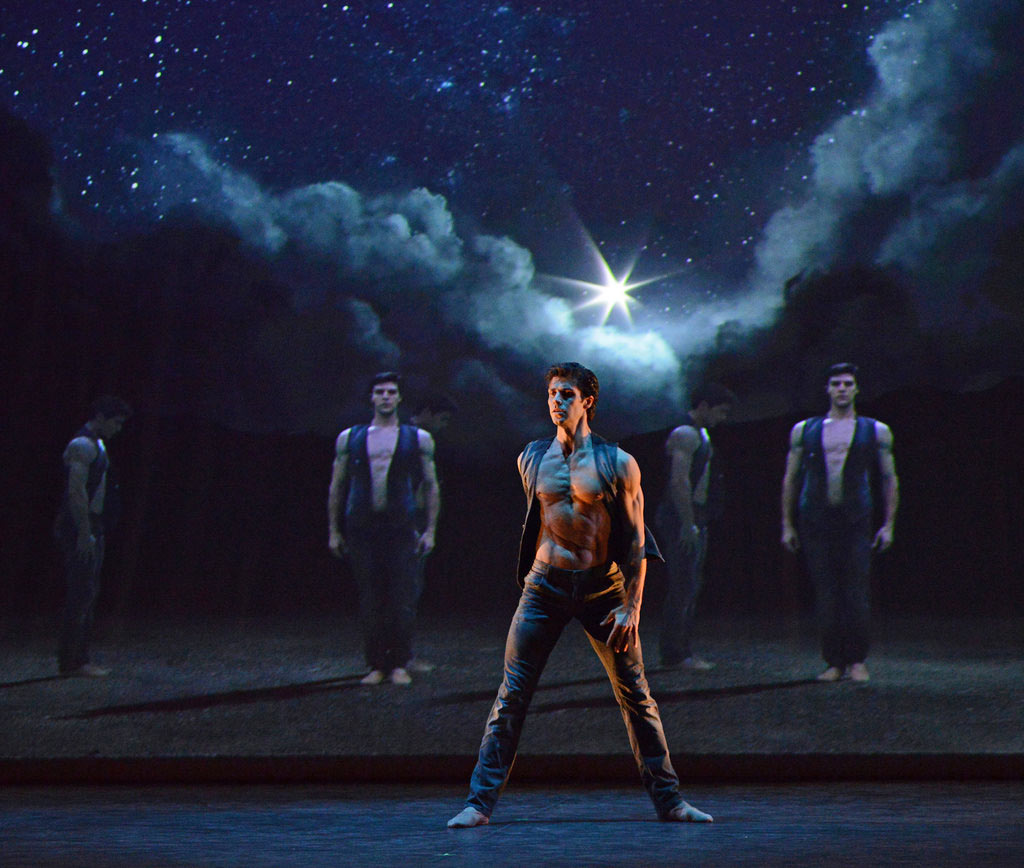

Roland Petit famously substituted Bach’s Passacaglia at the last moment for Le Jeune Homme et la Mort, exploiting the contrast between classical music and post-war existential angst in 1946. Ivan Vasiliev as the young man updates Petit’s modernism by wearing jeans instead of paint-spattered dungarees and a (possibly) digital watch on his left wrist. He’s not so much an agonised Parisian artist as a Russian adolescent soul, raw and vulnerable. Taunted by Svetlana Lunkina’s femme fatale, he hurls himself at her, life and the furniture in his attic. Lunkina, with her triangular cat’s face beneath an overlarge black wig, is a tad too vicious: as his fate, she should be indifferent to his torments. She wields her slender legs like scimitars, sheathed in lethal pink pointe shoes – the ultimate ballet fetish. He kisses her satin shoe before she abandons him to the fatal allure of the noose she has knotted for him. Wonderful how Petit’s youthful melodrama still works its power, performed with commitment and coached by an expert – Luigi Bonino, one of Petit’s favourite dancers, now credited as ballet master for the Kings troupe.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

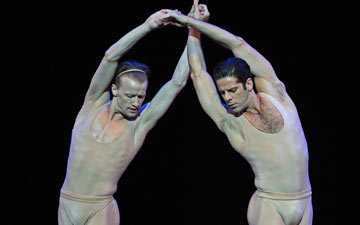

Some 30 years after Le Jeune Homme, Petit reprised the theme of the innocent and the tempter in the homoerotic duet from his Proust tribute ballet. Gomes was the dark seducer, Matvienko the desired youth, both luscious in flesh-coloured body tights. Even taken out of context, the male pas de deux proved more absorbing than the solos in the final section. Roberto Bolle (alternating as le jeune homme) performed a narcissistic tribute made for him by a frequent collaborator, Massimiliano Volpini. Prototype refers via videos and props to numerous roles Bolle has danced, enabling him to duel with himself as Romeo, lament as Albrecht, strut beneath suspended cherries from in the middle somewhat elevated, strip and re-dress while executing banal choreography in front of projected imagery.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Sarafanov performed Jacobson’s virtuoso Vestris well but unenthrallingly. Valentino Zuchetti was more vivid in his Men in Motion account of the solo. Vasiliev roused audience excitement, including a standing ovation from Natalia Osipova, in his passion-torn solo by Patrick de Bana, Labyrinth of Solitude. Prey to conflicting emotions, Vasiliev flung himself into the air and flashed round the stage in split jetés, never sparing himself. The poster boy for the Kings tour, he is undoubtedly the power-house of the troupe. Within moments of finishing the exhausting solo, he was back on stage for the finale with the other four in Gomes’s KO’d to a piano sonata by Guillaume Coté, dancer, composer and former King. The lads bounded and bonded in friendly rivalry, making us wish we’d seen more of them as individual personalities and as interpreters of more rewarding choreography.

You must be logged in to post a comment.