© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

English National Ballet

Lest We Forget: No Man’s Land, Second Breath, Dust, Firebird

London, Barbican Theatre

2 April 2014

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

www.ballet.org.uk

www.barbican.org.uk

Tamara Rojo is challenging English National Ballet’s dancers, as well as its audiences, by presenting it at the Barbican as a contemporary ballet company. The theatre, alas, was not intended for dance: no orchestra pit, awkward access to the stage behind the scenes, baffling access to foyers for unfamiliar ballet goers. But everyone learns to adapt – though placing musicians under the stage and miking them is not a satisfactory solution.

Rojo’s intent in commissioning new works is to discover different dance languages in contrasting approaches to the same subject: the Great War, a century on. The choreographers she has chosen – Liam Scarlett, Russell Maliphant and Akram Khan – investigated archives and literature, coming up with ideas that inevitably echoed each others’. The result would be a coherent programme, were it not for the revival of George Williamson’s (reworked) Firebird, created for another context.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Since ENB has a large female corps de ballet, the choreographers were bound to emphasise the roles women played during the First World War, working in munitions factories and hospitals. Liam Scarlett and his designer, Jon Bausor, address head-on the fact that women were making lethal weapons as well as nurturing soldiers. The set for No Man’s Land has a factory bench at the back, on high, with winding ramps descending to the battle ground below. The women’s mechanical gestures as they assemble artillery shells and bullets (which stained their hands yellow, hence gloves and a sulphuric glow in Paul Keogan’s lighting) are juxtaposed with the men’s agonies in the trenches.

Very effective ideas are scuppered by Scarlett’s recourse to clichés, starting with silent screams from splayed pliés. Before the soldiers depart, the women cling to their men from behind, their arms resembling the canvas straps of kit bags: all too readily, however, the women appear burdens or angels, their skirts flaring like wings. Back at the factory bench, they sink their heads into their hands in exhaustion: the men fall and writhe in protracted death throes.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Three couples are highlighted in pas de deux. First Tamara Rojo is swung aloft by Esteban Berlanga; then Fernanda Oliveira, led by Max Westwell, clutches her womb and wrings her hands; Erina Takahashi, arms upraised, is bewildered by James Forbat’s shell-shock. The music is Liszt piano pieces, orchestrated by Gavin Sutherland, who can’t quite disguise the echoes of Mayerling and Marguerite and Armand. The saddest music is for the long concluding duet for Rojo and the ghost of Berlanga. Tragically ecstatic, it is bound to end with him slipping away from her arms, like Giselle, while she stares hopelessly into the future. Yes, it’s a young man’s ballet, but Scarlett has surely seen enough to be aware of overused emotive gestures and poignant endings.

George Williamson, even younger, has turned Fokine’s Firebird into an ecological fable about man plundering nature. It would be a stretch too far to compare its motif of infernal profiteers to the cynical warmongers in Kurt Jooss’s The Green Table. This Firebird serves to fill out the evening, followed by a musical interlude to allow Junor Souza to change his costume for the third work, Maliphant’s Second Breath.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

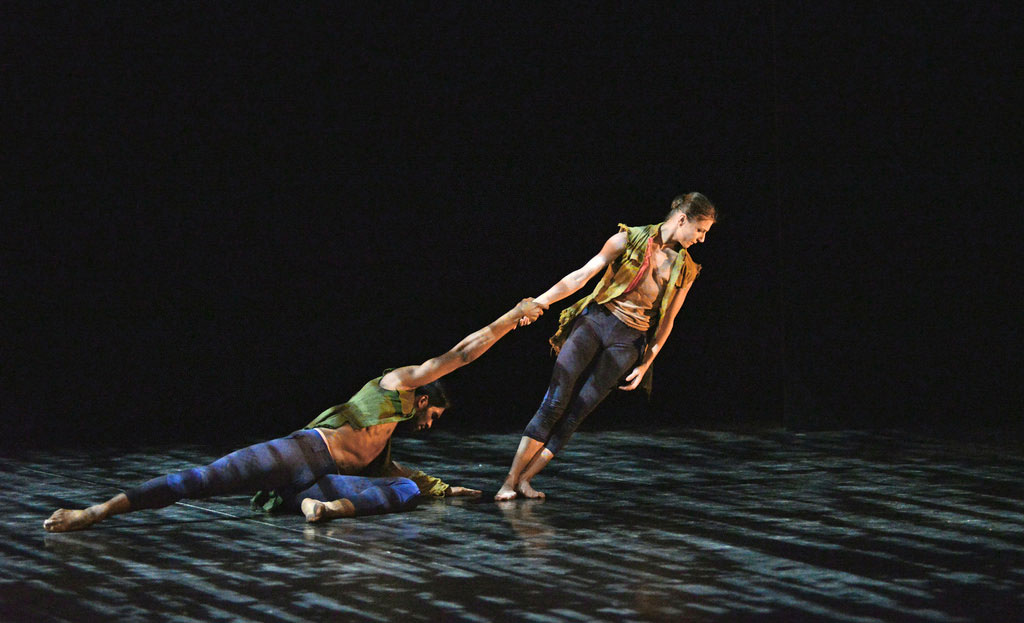

Set to Andy Cowton’s commissioned score, it starts in silence with 20 khaki-clad dancers swaying uneasily in a barren landscape. Spectral voices recount in German, Italian and English the vast numbers of deaths in battle. The sexes separate to form sculptural tableaux, seemingly based on war memorials, photographs and paintings. A gleaming figure is upraised in Michael Hulls’s sepulchral lighting, while others tumble in the darkness. When ensembles sweep across the stage, more balletically than usual for Maliphant, their lines rather too often resort to canon sequences, one dancer swiftly following another. A duet for Alina Cojocaru with Souza is achingly moving, their bodies slowly pulling apart, their emotions disparate: their experiences have been so different that they can no longer connect. No expressionist clichés in this requiem.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Akram Khan’s Dust contains elements of the previous pieces in the programme, as well as of his own works. His achievement in his first work for a big ballet company is to create a very personal response that is mythic enough, abstract enough, to embrace all wars. He is the main male figure, taking on the suffering of everyone involved. Alone at first in an agonised solo, he is joined by a phalanx of linked figures who emerged from the gloom behind him. They clap their hands, raising clouds of dust that linger like mist or poison gas. Holding on to each other, their arms undulate like ropes, binding them together, tying them to Khan.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

They split apart, men going over the top of sandbags at the rear, women commanding the foreground as whirling warriors, death-delivering machines, elemental forces. This is an unaccustomed way of moving for ballet dancers, earthbound and propulsive. An unusual emphasis is on their hands and fingers, as graphic as South Asian kathak dancers’ rather than ballet’s folded palms. Jocelyn Pook’s score combines percussive thumps and bangs with soaring strings, swelling and swelling. Then she adds a crackling archive recording from 1916 of a soldier chanting ‘We’re here because we’re here because we’re here’. Too similar, alas, to Gavin Bryars’ use of a tramp croaking ‘Jesus’ blood never failed me yet’ in the score for William Forsythe’s Quintett – for those who know that beautiful lament.

© Dave Morgan. (Click image for larger version)

Dust concludes with a mesmerising duet for Khan and Rojo, alike in height and supple fluidity of movement. They become a double image of male and female, warrior and nurterer, as she hangs from his waist and takes turns in supporting him. They balance each other, forehead to forehead, chest to breast. Rojo can accomplish the kneeling spins of kathak as well as the arching backbends of ballet – an ideal complement to Khan. At the end, their linked arms have to separate as he goes up the sandbag wall and she remains spinning alone as darkness falls. Cliché ending narrowly avoided (a lesson for Scarlett) because the extraordinary mirror images in the duet linger longer than the foreseeable final one. A resounding success for Khan as creator, Rojo as artistic director and both as performers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.