© Gregory Lorenzutti. (click image for larger version)

gl-hex-james-welsby-look-red-ribbon_1000.jpg

James Welsby

Next Wave Festival: Hex

Melbourne, fortyfivedownstairs

6 May 2014

jameswelsby.com

nextwave.org.au

www.fortyfivedownstairs.com

In 1994 American choreographer Bill T. Jones presented Still/Here, a work that featured interviews with terminally ill cancer and AIDS patients gathered through “survival workshops”. Jones had been diagnosed with HIV and his partner, Arnie Zane, had passed away from complications due to AIDS in 1988. The dance critic for The New Yorker, Arlene Croce, refused to see, much less review, Still/Here. In a stunning attack on what she dubbed ‘victim art’ in her article, “Discussing the undiscussable,” Croce referred to Still/Here as “a kind of messianic travelling show, designed to do some good for sufferers of fatal illnesses.” This was, Croce argued, a piece of art that existed “beyond criticism,” and in her decision to write about a work that she had never seen (but which had been highly publicised and documented), she played her role in a larger culture clash of the era.

Croce’s article sparked a furious debate about the nature of arts criticism and about the ethics of artists using (or exploiting) human experience as inspiration for contemporary art. Responding in the New York Times, American author Joyce Carol Oates asked “Why should authentic experience, in art, render it ‘beyond criticism’?” pointing to the work of Sylvia Plath, Anne Frank, Edvard Munch and others who translated human tragedy into artistic product. “What is it about AIDS that provokes a fierce recoil,” asked Adam Mars-Jones in The Independent the same year, noting that one of the significant parts about Croce’s comments (as with the reaction to Mapplethorpe’s exhibition being withdrawn) was that they were about AIDS, a virus that had first appeared in homosexuals and drug users. These communities existed outside mainstream culture and had long attracted condemnation from right-wing commentators. Mars-Jones continued, asking, “And more crucially, what is an artist personally affected by HIV to do, if not include it in his or her working practice?”

Other commentators drew comparisons with the 1989 scandal when a gallery cancelled an exhibition of Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs, noting that, as with Still/Here, Mapplethorpe’s work featured depictions of AIDS and homosexuality and sparked debate about the public funding of controversial art. By the time Jones’ work premiered, HIV/AIDS as inspiration was a part of an emerging trend in performance; two years earlier, Tony Kushner’s play Angels in America had rocketed the disease into the mainstream, and only a year after Still/Here premiered, Jonathan Larson would reimagine Puccini’s La Boheme as rock musical RENT, in which a number of main characters have contracted HIV/AIDS. New York, meanwhile, was reeling from its devastating effects, but was by no means alone across the world. The dance community was arguably one of the hardest hit with the loss of Rudolf Nureyev, Michael Bennett, Alvin Ailey and many more talented dancers and choreographers lost in the space of a few years; Bill T. Jones was one of many who had been touched by the disease.

© Gregory Lorenzutti. (click image for larger version)

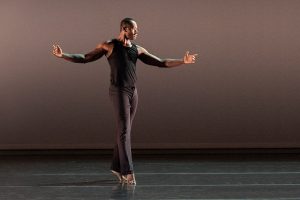

James Welsby’s Hex, which premiered as part of the 2014 Next Wave Festival, can be read as a kind of bookend to Still/Here. It has been informed by more than twenty years of queer activism and art following on from Larson, Kushner and Mapplethorpe and in response to contemporary dance artists such as Jacolby Satterwhite as well as the popularity of Drag/Femme Ballroom Vogue battles. In the same way that Croce’s article, “Discussing the undiscussable” demanded a mainstream response to content that had been cultivated in queer subculture, Hex opened amidst (an albeit smaller) convergence of mainstream and sub-culture: the day that Hex ended its season, drag queen Conchita Wurst won the Eurovision song contest, and NFL player Michael Sam became the first openly gay American National Football League draft selection. Both events sparked a backlash of homophobic rhetoric on the internet and television in Australia and overseas. In an era in which debate over gay marriage has waxed and waned, and where performative elements of black and queer culture such as twerking and vogueing have well and truly been appropriated by mainstream artists (case in point: Miley Cyrus), Hex is a work that is a product of contemporary Australian culture, even as it looks to history for its inspiration.

Like Jones, Welsby prepared for his work by interviewing HIV/AIDS sufferers. Unlike Still/Here, Hex applies an abstract filter to the content Welsby has gathered, resulting in a performance that is rich with cultural connections and threads but is careful in its confrontation with the audience. Welsby has brought a sense of joy to Hex, drawing on club culture and vogueing to balance the reality of illness. The work traverses a number of ‘dance’ breaks: jazz runs and kick-ball changes, and evolves through some of the more familiar vogue moves, including spectacular tucked leg falls, hand illusions and strutting walking and posing. In a protest scene, shouting voices are heard demanding justice, while dancers pump the air and stamp the ground. Later, those same gestures form the scaffold for a dance of freedom and defiance. This scene, like several in the work, is a little too long. However, there is something intriguing in its rawness and the way that historical events have been incorporated.

Welsby was born in 1987, the same year that the Australian Government’s ‘Grim Reaper’ AIDS/HIV awareness television campaign went to air. This public service announcement featured people lined up like bowling pins, with row after row of Grim Reapers bowling them down. In the vein of Australia’s safe driving and anti-social commercial campaigns (renowned for their violent depictions of death and injury), the Grim Reaper commercial showed men, women, crying children and infants dead on the floor while a voiceover warned that “if not stopped, it could kill more Australians than World War II.” Welsby cites this startling campaign in his program notes as a cultural signpost, and makes his first appearance in the work in costume as ‘Death’, with a bedazzled mask obscured by a black veil. Brandishing his scythe, Welsby, as Reaper, gyrates to the steady thump of disco, and is backed up by dancers Benjamin Hancock and Chafia Brooks. The veils come off to reveal an ordinary man in a mesh t-shirt and jeans but with the reappearance of the scythe towards the end of the work, it is clear that the Reaper has not been forgotten altogether.

© Gregory Lorenzutti. (click image for larger version)

Welsby’s use of vogueing is more reminiscent of the Madonna-era of precision, rather than the looser, more fluid physicality of contemporary vogue. Dancer Benjamin Hancock finds the loose-limbed, arched-back posture at some points, but Hex’s choreography draws the dancers into stylised and formalised unison more often than it allows for the individual expression and aggression of contemporary vogue. The posed sequences, reminiscent of fashion models, as well as the extended hand illusion sections, create a kaleidoscope of organised and entwined limbs, heightening the suggestion of a community onstage as opposed to a battle between individuals. To suggest that Hex is offering vogue-lite is to misread the nature of this work; by utilising traditional and formalistic style of the genre, Welsby is making a historical and cultural statement, situating the work in the late 20th century even as he applies very contemporary filters to the content.

Welsby also embeds Hex in the 1980s and 1990s through his use of music, sampling Queen’s Another One Bites the Dust remixed by Claudio Tocco, as well as music by Peter Allen, Liberace, and Klaus Nomi (all AIDS sufferers). As the music breaks down with pops and crackling feedback, the unison and formalistic elements of the movement give way to a very different aesthetic. Welsby and Hancock sit entwined, lips only centimetres apart. It looks like the moment before a kiss, but the dancers begin to hum and then shout into each other’s open mouth. This moment of intimacy represents a kind of transmission- of information, history, and- more literally perhaps- of a virus. As the screams reach their maximum pitch, Hancock lies across Welsby’s lap, exhausted. Welsby leans forward to repeat the sequence with Brooks, who had previously watched, still, from the side. The dancers struggle to rise and regain their organised choreography, with one or another dropping off from the steady rhythmic choreography.

In another effective scene, the dancers don hot-pink rubber gloves. This is a nod to cabaret and drag, but also perhaps a reference to traditional gender stereotypes. As the dancers begin to discard their gloves the references become more serious: injections and treatments at a doctor’s office or lab clinicians at work searching for a cure. However, and perhaps most obscenely, these limp, discarded gloves appear to reference used condoms — a reality for sexual activity for all adults today in the way it would not have been for those who came of age in the 1970s.

In his program notes, Welsby mentions how rarely stories are shared between generations of gay men. For adults of Welsby’s age, having always grown up with the reality of HIV/AIDS, fear of the disease has been somewhat mitigated by education and treatment. Hex traverses a range of emotions – from joy to anger and lust – but fear is not chief among them. However, as Welsby points out, incidences of AIDS/HIV are again on the rise in Australia. But where, Welsby seems to ask, is the spectre of the Grim Reaper for this generation?

Where is the fear?

© Gregory Lorenzutti. (click image for larger version)

Political activism through dance has been thin on the ground in Melbourne, with the independent contemporary dance scene preferring investigations into structure and minimalism in recent years. One notable exception is Phillip Adams, whose company, Balletlab, has spent the past few years creating work inspired by quirks of American culture in the 1970s- religious cults, horror films and fascination with Roswell. Later this year, Adams and visual artist Andrew Hazelwinkel are premiering a new work called LIVE WITH IT, we all have HIV that will offer a portrait of Australia’s three-decade-long history with the virus.

Hex may signal a shift underway in Melbourne towards activism in performance. On its own, this is an ambitious piece of dance theatre created by an emerging choreographer that drives its message home through sheer determination, but without the benefit of expensive production values. Although it still needs tweaking in terms of its structure, Welsby has created something powerful that both celebrates and questions the weight of history.

Welsby, a graduate of the Victorian College of the Arts, made a handful of full-length works before Hex, but none have resonated as well. Hex is an enormous step up and forward, and a sign of his promise as a dancemaker.

–oOo–

i) Croce quoted in Sinfield, Alan. “Stephen spender’s bit of rough: Some arguments about art, AIDS, and subculture.” European Journal of English Studies, 1(1), 2008, pp 65

ii) Oates, Joyce Carol. “Confronting Head on the Face of the Afflicted.” New York Times, 19 February 1995.

iii) Mars-Jones, Adam. “Victims don’t make art.” The Independent, 15 March 1995.

iV) Mars-Jones, 1995 http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/victims-dont-make-art-1611300.html

v) Teachout, Terry. “Victim Art.” Commentary, March 1995.

vi) “Grim Reaper [1987]”. Youtube video. Posted by Paul Kidd, accessed 14 May 2014. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U219eUIZ7Qo

Thanks, Jordan, for this thoughtful piece (a literature/ documentation survey morphing into a necessarily [?] limited commentary on some performance moves and momenta). I find it sad that Fairfax can’t find room for this kind of sequence. I’m not clear what you mean by ‘activism’. I think an individual, a reader and an audience ever participate with the artwork and staffage in activism. We have no choice. To measure the happening by its employment of activism tells us nothing. Participation is ever ideolgical and activist. ‘Swan Lake’ does activism too. It can’t help it.

Thanks for your comment Peter. I take your point- we can all be changed and inspired by performance. I suppose I see a difference between responsiveness as an audience member- be it kinesthetic, emotional and/or intellectual responsiveness- and activism. In this case, I think Hex is drawing on a kind of political activism and it is the ‘political’, rather than the ‘activism’, that I meant to draw attention to. I may be wrong in suggesting this as an early trend in Melbourne contemporary dance- but I thought it worth noting down in this case.

[…] Author: Jordan Beth Vincent Description: Review Location details: Hex (web […]