© Herman Sorgeloos. (Click image for larger version)

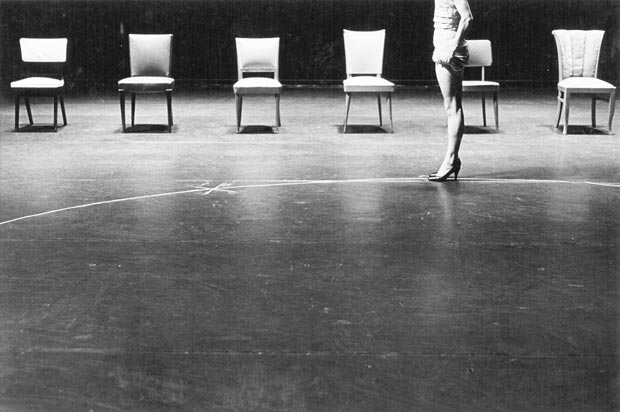

Rosas – Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker

Elena’s Aria, Bartok/Mikrokosmos

New York, Gerald W. Lynch Theatre

14 and 15 July 2014

www.rosas.be

lincolncenterfestival.org

De Keersmaeker, Early Works

After experiencing four of Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker’s early works in quick succession at the Lincoln Center Festival this week and last, I think it’s safe to say that she is an artist who follows her obsessions with a tenacity that is both admirable and frequently defeating. I’ve seldom seen so many people leave a performance as I did the other night (July 14) during Elena’s Aria, except, perhaps, last year during a performance of her En Atendantat the Brooklyn Academy of Music. In each of the four works being shown at the festival, and from one work to the next, De Keersmaeker insists upon a small reserve of steps with the relentlessness and self-abnegation of a religious penitent.

© Herman Sorgeloos. (Click image for larger version)

This hyper-deliberate reiteration of a handful of steps can be exhilarating and even virtuosic, as it is in her first work, Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich, a tour-de-force constructed out of cycles and variations on few simple themes, each performed with extraordinary precision: arm swinging, twirling, hair-swishing, and hovering on tiptoe. None of the subsequent pieces achieve the tautness of that work, but then again, another work in the same vein would be pointless. But the overlap between one piece and the next eventually undermines the freshness of the movements themselves. There is a lot of recycling: whirling turns and gliding sashays like something out of a Rita Hayworth movie, coquettish steps on tiptoe, chair dances, stomps and bends that emphasize womanly rear ends, skittering runs and skirt-flipping, with now and then a glimpse of white underwear. It’s not just the movements, but also the patterns, that repeat ad nauseam: side to side, front to back, on the diagonal, in a circle. Back and forth they go. The rigor is admirable, but after a while exasperation sets in.

The music in Elena’s Aria and Bartok/Mikrokosmos opens windows to other realities, but the dancing remains doggedly consistent. The two coexist but don’t converse. Cannily, De Keersmaeker refers to this tension directly in Bartok/Mikrokosmos (July 15): there is a perverse passage in which a pair of dancers stands perfectly still through an entire performance of György Ligeti’s Monument for two pianos. They move only to turn the pages of the score. When the pianists finish playing, they turn around and leave. (The Ligeti pieces were played with wit and vibrant contrast by Jan-Luc Fafchamps and Laurence Cornez.)

© Herman Sorgeloos. (Click image for larger version)

According to the program notes, the second half of the evening,set to Bartok’s String Quartet No. 4 – lushly played by the Ictus ensemble – is about “the pleasure of dancing and playing together”; four women click their heels and whirl with girlish pleasure until they wear themselves out. But one can’t help feeling that the choreography has barely scratched the surface of the music, with its rich textures and changes of mood. The opening dance, set to Bartok’s charming short piano cycle Mikrokosmos, was more responsive, in part because it featured an anomaly: a male-female pairing. It was a welcome change to see De Keersmaeker’s dance-steps performed by a man (Jakub Truszkowski), without any of the coquettish flourishes that return again and again in these early works. And what a pleasure to finally see some human contact; it is the only of the four works performed during the festival in which the dancers actually touch.

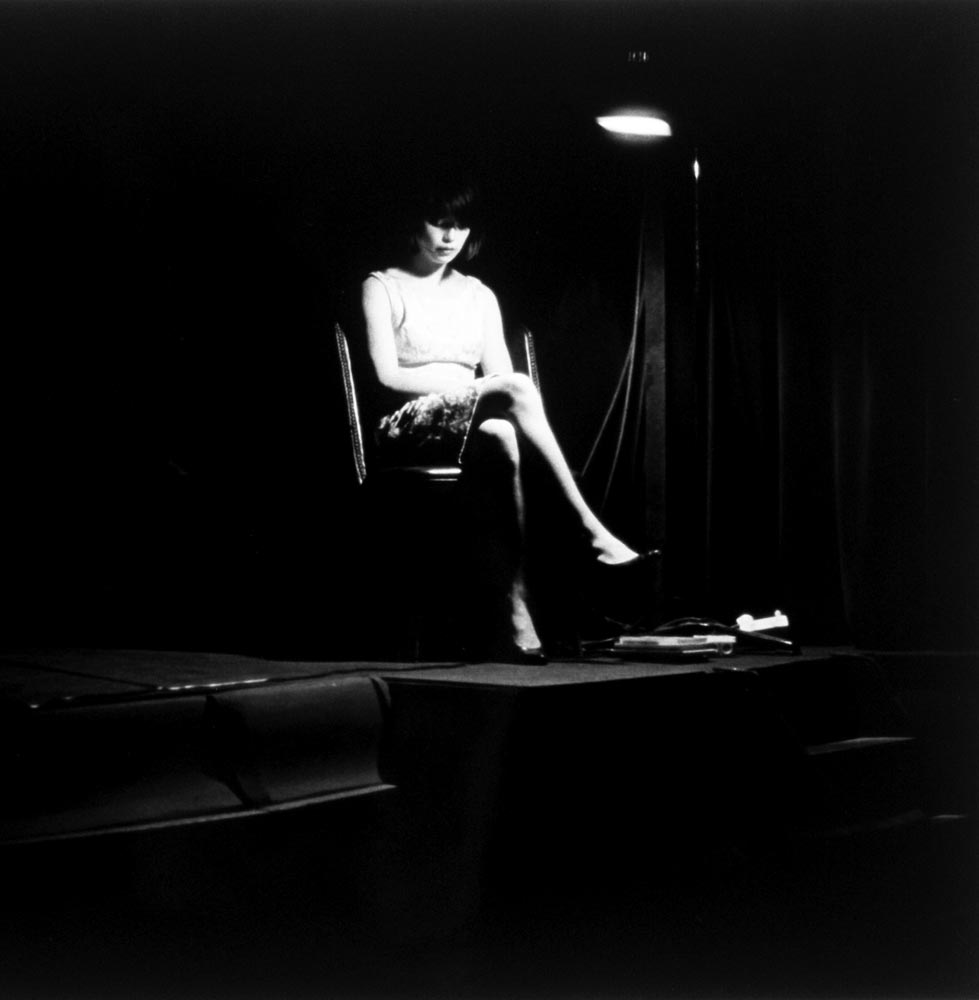

In Elena’s Aria, De Keersmaeker wades into more turbulent waters. The piece is a portrait of feminine dejection. The mischievous schoolgirls of Rosas Danst Rosas have grown up and fallen in love, discovered literature and sex and maybe politics. As in Pina Bausch’s world – the influence of Bausch seems undeniable – the women face their misery clad in high heels and party dresses. Their hair hangs over their shoulders. The dancers’ femininity is central to the work: they bend and crouch, accentuating the curve of their back-sides, and pull their skirts up to reveal taut dancers’ thighs (including De Keersmaeker’s). But their sexuality, readily displayed, also renders them vulnerable. They slump on chairs – so many chairs! – limp-armed, lie dejectedly on the floor, stare blankly into space. For long periods, they don’t move at all.

© Herman Sorgeloos. (Click image for larger version)

This would be dreary indeed if it weren’t for De Keersmaeker’s canny musical and literary choices. At various points, dancers walk over to an area to the right of the stage, sit in an armchair, and read passages on love and friendship from War and Peace (in French), Berthold Brecht’s Happy End (in German), and Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot (in English). The passages supply a certain context to the dancers’ otherwise generic suffering. At other times we hear, faintly at first, old recordings of Neapolitan melodies and opera arias (from The Pearl Fishers and Lucia di Lammermoor) sung by Caruso and others. The emotional intensity and purity of these voices overpowers the dancing, and yet without this infusion of energy, the piece would fall apart.

De Keersmaeker also dips her toe into politics, albeit in the most ambiguous manner: we hear a passage of a Che Guevara speech to the UN, in which, in Spanish, he decries imperialism, exploitation, and the domination of one race by another. Like the urgency of Caruso’s voice, the politics remain disconnected from the dancers’ activity, hovering in the air like a memory. But it’s not enough. In the end, Elena’s Aria is dragged down by the lethargy and repetitiveness of its choreography.

You must be logged in to post a comment.