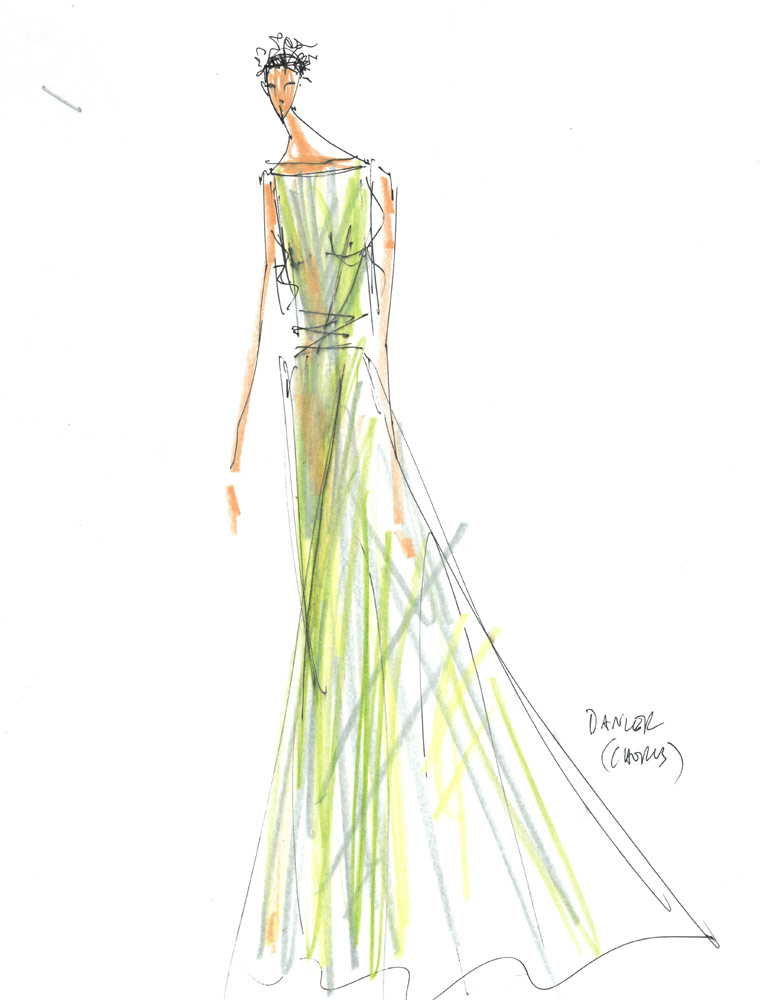

© Isaac Mizrahi. (Click image for larger version)

Mark Morris Dance Group

Acis and Galatea

New York, David H. Koch

8 August 2014

markmorrisdancegroup.org

mostlymozart.org

www.philharmonia.org

Crystal Fountains

As he has shown again and again, the choreographer Mark Morris has a way with Baroque music. He clearly adores it, both for its rhythmic pulse and for its directness of expression, both of which make it great music to dance to. But happily his adoration does not translate into slavish reverence. In the music of Purcell, Vivaldi, Bach, and Handel, Morris seems to find a happy conduit for his imagination, in which bawdiness and sincerity, generosity, darkness and, at times, a curious emotional reticence go hand in hand. This music speaks to him, and through it, he speaks to us.

Morris’s staging of Handel’s pastoral opera Acis and Galatea, written in 1718 at the summer estate of his patron, the Duke of Chandos, is currently on show at the Mostly Mozart Festival. The production, enhanced with bold, luminous green-and-blue overlapping scrims by Adrianne Lobel and matching costumes by Isaac Mizrahi, and played by the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra and Chorale (led by Nicholas McGegan), has been many months in the making and premièred earlier this year at Cal Performances in Berkeley. Morris has used the 1788 orchestration by Mozart, which is fuller than Handel’s but keeps the essential palette intact. He has retained the original English texts composed by the pastoral poet John Gay (with a little help from Alexander Pope and John Hughes). As always with Morris, the words are important; not only does he ask for (and for the most part obtain) clear enunciation from his singers, but, for good measure, the dialogue is also projected above the stage. The direct link between gesture and text is an essential part of the audience’s experience of the work.

Unlike his Dido and Aeneas (1989) and L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato (1988), in Acis Morris places the four soloists – the wonderful lyrical soprano Yulia Van Doren, tenors Thomas Cooley and Isaiah Bell and baritone Douglas Williams – onstage among the dancers. The chorus is down below, with the players. (Morris also took this approach in his delightfully zany staging of Purcell’s King Arthur, staged at New York City Opera in 2008.) Here, the singers and dancers share the same world, in relative harmony.

There is an inescapable awkwardness to placing singers and dancers side by side. Singing requires an inward focus that is in stark contrast to the physical extroversion of dance. Morris has handled this tension in various ways. Often, he diverts attention away from the singers, who remain relatively still, on the sidelines. They are also dressed differently, in something approximating casual dress rather than Mizrahi’s flowing, foamy skirts for the ensemble. (The male dancers are bare-chested.) The viewer can choose to watch them or, more likely, to train his eye on the dancers, who illuminate the words and the shape of the music with their movements. Other times, Morris has the dancers surround the vocalists, or lead them, or envelop them in waves. Only once, toward the end of the opera, does he allow the sweet-voiced Van Doren to take the stage alone, without distractions, to sing the heart-rending aria “Must I My Acis still Bemoan?” (Acis has just been killed by a boulder flung by Polyphemus, in a jealous rage.) Her stillness comes almost as a relief. It is the most touching moment in the opera.

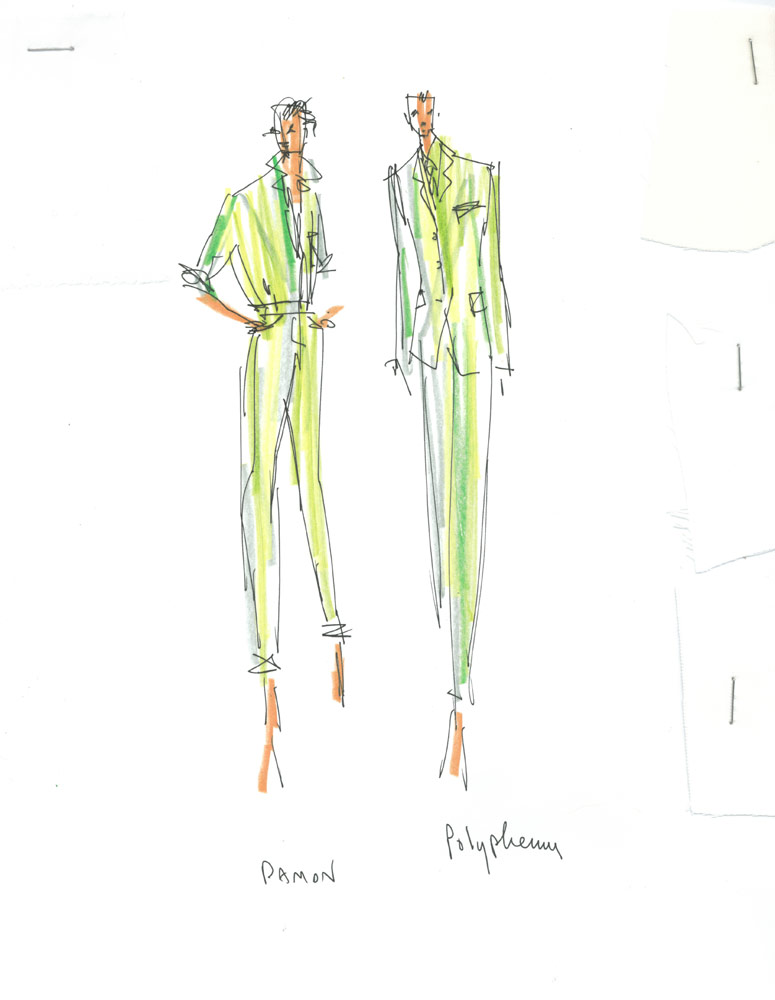

© Isaac Mizrahi. (Click image for larger version)

I am less convinced by the tactic of choreographing the singers’ hand gestures, creating a kind of manual accompaniment to their voices. The effect, while elegant, is unnatural and has the unfortunate effect of distancing us from the emotions they are trying to express. Acis and Galatea’s longing for each other and Polyphemus’s anger fail to register until the very end, when the innocent shepherd (the high tenor Thomas Cooley) lies dead at the hand of Polyphemus (Douglas Williams). (The very simple story, which Morris dispatches in four lines in the program, is drawn from Ovid.)

Morris’s natural jokiness can also get in the way of the music’s natural punch. When Damon (Acis’s friend, played by Isaiah Bell) sings of flocks straying through the valley, the dancers prance around like sheep, which gets a laugh, but also breaks the atmosphere in what is really a touching aria about friendship and concern. Morris’s humor is an integral part of this style, but it can tread a fine line between sublime irreverence and silliness. Morris’s more illuminating impudence reveals itself later, in Polyphemus’s famous “O Ruddier than the Cherry,” during which a line of pouty nymphs parades before him, even as he unceremoniously grabs various parts of their anatomy.

The part is sung by the improbably handsome baritone Douglas Williams, dressed in a gorgeous Mizrahi suit decorated with the same green pattern that covers the nymph’s flowing costumes. (It’s probably not an accident that in Morris’s version the evil character is better-looking than the hero.) Morris campily depicts him as a cartoonish sexual predator, preying on men and women alike and slobbering over Galatea with masturbatory lechery. The story of Acis is driven by sexual attraction, and Morris, in his raunchy way, doesn’t let us forget it.

Another masterful stroke comes during Acis’s “Love Sounds th’Alarm,” a rather tedious, march-like aria that seems to go on forever. (Repetition is an inescapable feature of Baroque opera.) Morris cannily distracts us with a brilliant folk dance for one of the nymphs, built from a mix of Irish step dancing – with big, stiff-legged pas de basques – and angular, flat “archaic” steps in the style of Nijinsky’s Après-midi d’un Faune. Alternately launching herself into the air and then flattening her arms and legs like a figure on a Greek vase, the tall, imposing Lauren Lynch zig-zags her way across the stage. As she reaches her destination, several other dancers appear from the wings and begin a canon, facing in different directions, eventually forming several groups. It’s a perfect example of how Morris can take one beguilingly simple unit of dancing and turn it into a wondrous maze.

It’s also fun to watch the echoing of motifs throughout the piece, such as a serene pose in which two dancers recline on the floor, one in front of the other, like a married couple on an Etruscan sarcophagus. Our eyes catch these little images, which register like shiny cobblestones caught by the sun – there it is again! Don’t be fooled by Morris’s raunchiness or the softness of his movement style; he’s as punctilious about structure as anyone. The ensemble dances that frame the evening are marvels of construction and patterning.

© Isaac Mizrahi. (Click image for larger version)

Regarding his taste in singers, with the exception of Van Doren, Morris seems to prefer slight, not-quite-operatic voices with little vibrato and an un-focused sound that may be appealing to early-music lovers but have trouble filling a large (and acoustically-challenged) venue like the Koch Theatre. Nor do the acoustics of the house favor the period-instrument sound of McGegan’s Philharmonia Baroque ensemble, which is a shame. After hearing the Bolshoi orchestra in the same theatre just a few days ago, they sounded positively muffled.

Despite such quibbles, Morris’s Acis is a very enjoyable way to spend an evening. The dancers are strong, straightforward, highly individualized; they fill the stage with their personalities and their full-bodied dancing. And, if this new work is not as imaginative as his L’Allegro or as vital as his Dido and Aeneas or as profound as his Gloria, well, few things in this world are.

You must be logged in to post a comment.