© Pegasus Books. (Click image for larger version)

Interview with Tina Sutton

www.themakingofmarkova.com

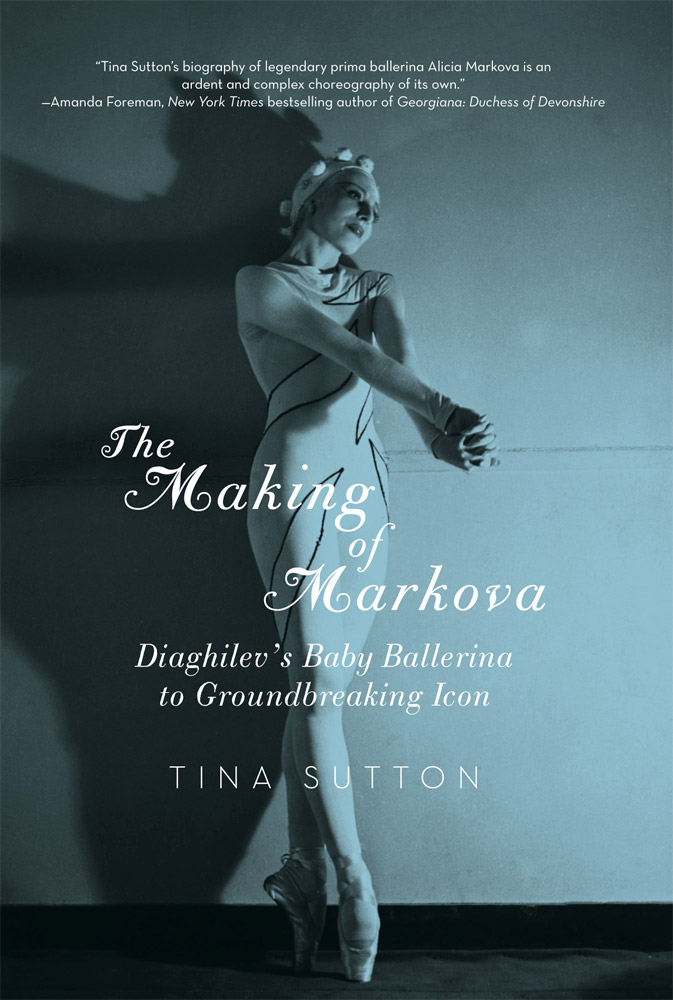

The Making of Markova: Diaghilev’s Baby Ballerina to Groundbreaking Icon

Pegasus Books

Published in paperback 2 September, at £12.99.

Publishers page

Markova Archive at Boston University Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center

Tina Sutton said in her interview with Jann Parry that her book about Alicia Markova is an exploration of the factors that made the dancer – not a conventional biography. Yes and no. Sutton stresses the parallels between Markova and Anna Pavlova, the idol of both Markova and her mother. And we learn much about Markova’s formative training and performances before she became the youngest member of the Ballets Russes – but what follows is a conventional life story, detailing Markova’s performances around the globe. Hers was a jet-setting career before the advent of fast plane travel.

Another point of difference in approach is that Sutton claims to rely entirely on material that she could verify, either from Markova’s collection of memorabilia donated to the archives of Boston University or from contemporary accounts. Sutton does not trust the subsequent memories or personal recollections of others. Evidently she would concur with Tamara Karsavina who once described Lydia Sokolova as having ‘a very good memory but she tends to rely on it too much.’

Yet Markova’s own recollections of the same incident vary between tellings. And Sutton leans heavily on published biographies to explain the history of the Ballets Russes or the subsequent development of ballet in Europe and America. No original insights are added to the description of the formative years of English ballet around 1930. The narrative chronology zig zags even within chapters. And details are repeated: Serge Diaghilev’s avuncular concern for Markova is reiterated more than once.

Sutton’s background as a fashion journalist leads to some surprising comparisons, as when she gushes that Markova’s departure from home to join the Ballets Russes was comparable to Marie Antoinette leaving Austria to become queen of France. Markova had the persona of young Jackie Kennedy we are told. Sutton is most at home detailing the jealousies of Léonide Massine and Serge Lifar when Markova danced with their companies in France and America – dangerous worlds somewhere between The Red Shoes and Black Swan. Her American career is made to sound like a constant backstage drama, akin to 42nd Streetor Kiss Me Kate.

Unsurprisingly Markova’s dance partner, Anton Dolin, appears unflatteringly. Dolin published four autobiographies and was famously narcissistic, but to claim he was Machiavellian is to misrepresent both men. Sutton argues that Markova’s role in the establishment of Festival Ballet – now English National Ballet – was belittled by Dolin. But the evidence offered here – advice to dancers on deportment and make-up – is rather thin. Markova’s archive apparently contains budgets, touring schedules and publicity plans for the companies Markova ran with Dolin, but the British phases of her career are only sketchily documented in comparison to the American years.

© Pegasus Books. (Click image for larger version)

Occasionally a comment emerges that perfectly encapsulates its subject. Markova is quoted describing the mathematical qualities of George Balanchine’s choreography where “suddenly the whole sum would come out right.” In 1931, Markova became Ashton’s muse, says Sutton, but she does not scrutinise that word’s meaning. Certainly Markova’s technical facility – and experience of working with Massine and Balanchine – elevated the potential of Ashton’s choreography. He despaired, however, of Markova’s remoteness. For Arnold Haskell, a lifelong friend, Markova was lost somewhere between an artless child and a consciously artistic woman. For Haskell, she lacked the ability to portray emotions. Diana Gould, Markova’s contemporary, described her as a head-girl vestal virgin, destined to become a high priestess of ballet.

That ethereal quality won Markova legions of fans for her performances as Giselle and in Les Sylphides. Markova’s ability to float is frequently acknowledged but not analysed. According to eyewitnesses during Markova’s guest appearances with The Royal Ballet, the impression of floating was as much to do with the strength of her partner. Markova was observed telling David Blair, ‘I don’t jump. You lift.’ That is the sort of reminiscence that Sutton does not trust. But neither do we learn from those dancers who were coached by Markova, her rehearsal methods or about productions she staged.

Markova’s detractors claimed she put herself at the centre of every event. When making his TV documentaries about the Ballets Russes, John Drummond complained she was incapable of relating an anecdote in less than 15 minutes. But such behaviour is not unusual for a performer accustomed to the spotlight. Markova was determinedly single minded in her desire to popularise. Her Giselle was first filmed for TV in 1932. She appeared on all manner of stages ill-suited for dance, for anybody, anywhere (having been first paid in advance, Sutton does not tell us). Any lessons for today – an age of cinema broadcasts when audiences for live dance are ever more discrete and fragmented – are not investigated by Sutton.

A stronger editorial eye would have been useful at times. Apparently Diaghilev’s Sleeping Princess played at Covent Garden. The Sadler’s Wells of the 1930s had a capacity of over 2,000 seats. Sutton is sometimes baffling in her American English. She is honest in her lack of knowledge about dance. When asked to write this biography she confused Markova with Natalia Makarova. Her narrative, however, is pitched for today’s world of celebrity culture.

Sutton positions Markova as an outsider, a sickly Jewish child who transformed herself into a superstar and became the most famous ballerina in the world. In her desire to construct a Girl’s Own adventure story Sutton’s claims – that Markova pioneered British ballet and was the first ballerina to establish an international career alone – lose their subtlety in the breathlessness of their telling. Such generalisations beg too many questions – and rather reduce Sutton’s obvious respect for Markova.

It’s a fun read.

An additional editorial edit: Lubov Tchernicheva was married to Grigoriev, not Lubov Egorova. The latter did dance for the Diaghilev company however.