© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

Chunky Move and Melbourne Theatre Company

Complexity of Belonging

A project by Falk Richter and Anouk van Dijk

Melbourne, Southbank Theatre

9 October 2014

chunkymove.com.au

www.mtc.com.au

www.melbournefestival.com.au

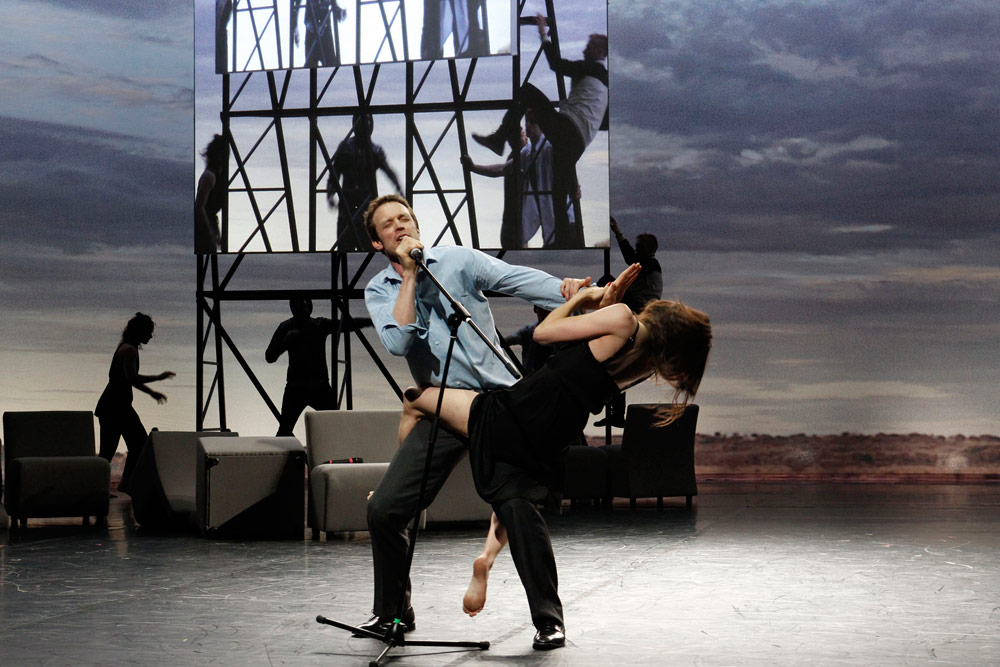

At first glance, the set for Complexity of Belonging has an old Hollywood soundstage feel, with its video cameras and lofty projection screen. An enormous panoramic image of an evening skyline curves across the stage. This is a bird’s-eye view, or a view from the cockpit of an airplane, or even a view inside a three-dimensional diorama; but it also seems a little bit like the characters in Complexity of Belonging are caught in a fishbowl, with all their foibles and insecurities magnified and made insignificant by their place within the artifice of their world.

Although the theme of waiting to land in an airplane is a touchstone for the work, the fishbowl might actually be the best analogy here. Complexity of Belonging vacillates between a kind of earnest, self-conscious obsession with itself and its own circular investigations, and something greater and more transcendent than the sum of its many movable parts. The work overflows with themes and sources of angst. From racism, gay marriage and international surrogacy to crumbling relationships, career struggles and the failure of communication in a digital world – Complexity of Belonging relishes its complications more than its attempts to speak in a coherent tone.

Complexity of Belonging is framed as an artwork within an artwork. Young artist Eloise (Eloise Mignon) is mounting a ‘human installation’ in a European gallery. The artefacts of her exhibition are drawn from her interactions with different people. She collects data in the form of stories, and presents them through notes, photos and, with the help of live-video feedback projected on the elevated screen, as larger-than-life fragments of evidence to be examined and chewed over. The use of live-video feedback introduces the theme of social media and Skype, and the potential to connect and disconnect individuals who cannot be brought together any other way. Many of the monologues are presented like Facebook rants- delivered with anger but without punctuation. In the way it exploits the performance of the self in an online forum, the work suggests, perhaps, that there is danger in making public too much of our private lives.

As a character, Eloise begins as an outsider- as both an objective interviewer and obsessive curator, probing her subjects for details about their parents, love lives, and childhoods. Her fascination is magnified large on the screen – asking questions, probing for truths. Later in the work, she becomes absorbed in the process of her curation, confessing her own secrets in the shadows or acting on her lust for one of her subjects. However, Complexity of Belonging is not really Eloise’s story, despite the fact that it begins with her artistic investigation. Each character is given a chance to reflect on their own issues; there is the therapist who has relocated to Australia from Europe and is tired of listening to the problems of her clients and her boyfriend. The boyfriend works too hard, travels too much, and has too little sex. A man reflects on his Asian heritage through the lens of the iconic 1992 Australian film, Romper Stomper, while another woman laments the fact that her appearance does not reflect her true self: ‘not Asian enough’, ‘not as spiritual as she appears to be.’

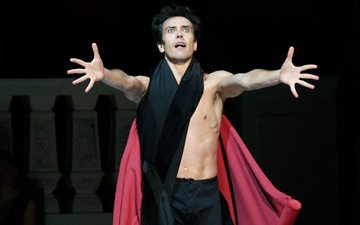

Complexity of Belonging is a collaboration between Chunky Move Artistic Director, Anouk van Dijk, and her long-term collaborator, renowned European theatre director Falk Richter. The cast is made up of five dancers from Chunky Move and four actors from Melbourne Theatre Company, although all both act and dance. Versatility varies across the cast: while dancers Lauren Langlois and Joel Bray and actor Stephen Phillips excel across both disciplines, the other performers demonstrate an uneven skill.

What comes across most strongly is the deft touch to the development of the characters through text, rather than through movement. Movement, in Complexity of Belonging, is often employed as a break between scenes, a filler, or something that happens in the background, but often with little relationship to the behaviour of the characters.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

The movement itself is drawn from van Dijk’s Countertechnique, a fluid dance style that forces the body into a place of instability. Choreography sees dancers falling from one spiral to the next, almost like a live Spirograph doodle. The traces are ephemeral, but as spiral sequences are repeated and layered, it almost feels as though the rotations are predetermined. Apart from the Countertechnique phrases, the rest of the movement is highly gestural and prop-based. A few times, the entire cast moves in unison, draping themselves off upholstered chairs or tipping backwards on two legs in dangerous defiance or shaky fear. Gestures are shared across the cast with the action of revealing bare torso – a demonstration of vulnerability – the strongest and most speaking. However, there are too few moments where this work reads as a true collaboration between movement and text, or where it feels as though a single thought is being expressed in the language of both mediums.

The best integration of text and movement is also the most troubling. In her confession to her therapist – and wearing red stilettos and a tight dress for the occasion – Lauren (Lauren Langlois) lists the qualities of her ‘perfect man’ from the simple (“he must be nice to me”) to the more unexpected (“he must look good on a horse”). In the background, Stephen Phillips manoeuvres chairs into a series of obstacles to climb up or leap over as a physical representation of the perceived absurdity of Lauren’s demands. As Lauren gets increasingly angry and demanding, she is forced into a wild and violent duet with dancer Alya Manzart. Langlois is dropped and rolled like a rag doll into different positions at Mazarts’ whim, landing with legs splayed before being whipped into the next implausible position. Even as she is spun through the air, Lauren continues her loud catalogue of ideal masculine attributes. This loss of control of Lauren’s physical self is presented in opposition to the kind of controlling, demanding and unrealistic expectations she expresses verbally. It is in this sequence that the true potential of Complexity of Belonging lies, and where the crafting of theatre with contemporary dance becomes a potent way to examine the individual and her place in the display. The audience rewarded Langlois’ performance on opening night with spontaneous applause. It was well deserved. However, there is something a bit troubling about the underlying assumptions that drive the sequence, and particularly in the way we see a woman’s sexual frustrations played out through violence.

This is not the only ethical grey area in Complexity of Belonging. The ‘characters’ onstage take on the real names of the performers, blurring the lines between real-life and theatrical confessions. As a theatrical device, this is nothing new. To what extent have the real-life struggles of these performers, and their own experiences of racism or homophobia, been mined for the purpose of exhibition- veiled, so very thinly, by the framing of ‘human installation?’ The investigation of reality versus artifice may well coalesce into the brilliance of the work, but as various struggles fail to move past their one-dimensional responses, it is also revealed as a significant weakness and a failure to push the craft of theatre-making quite far enough.

© Jeff Busby. (Click image for larger version)

Complexity of Belonging is the third major Chunky Move work since van Dijk became artistic director. In both of her previous productions, she emphasised the human body as a displayed curiosity. In An Act of Now (2012) dancers performed inside a glasshouse with group dynamics heightened by the inherent danger of highly physical dancing in a confined space. 247 Days, premiered in 2013, was a kind of companion piece to An Act of Now, with a mirrored set replacing the glasshouse. The combination of text and movement explored struggles with identity, an overwhelming sense of alienation and loneliness in a crowd, and the feeling of being simultaneously inside and outside a community. Complexity of Belonging is a work that exists in the same thematic vein, although it features far more text, which serves to tip the work from the realm of abstract dance into narrative-driven physical theatre.

As with the previous two works, Complexity of Belonging is a work about alienation and identity. This, too, is a work that investigates the self, as well as what we might mean by the phrase ‘Australian identity.’ This, too, is a work that self-consciously asks its performers to be revelatory and confessional in text, but offers movement that generally smooths the edges of the work rather than revels in the roughness. And despite the fact that the characters presented onstage have diverse interpretations of what a modern, or a ‘modern Australian’, identity might be, there exists a sense that fair dinkum’ Aussie stereotypes are overwhelmingly prevalent. In its obsession with the self- and particularly self-obsessed selves – Complexity of Belonging feels like a work made by an outsider looking in. You can sense a fascination and bewilderment with the notion of ‘Australian identity’ as well as with the strangeness, and even exoticism, of these Australian artists, woven with a desire to belong.

At the end, Eloise confesses her inability to retain perspective on her art; like the audience, she is the ultimate outsider turned insider, privy to the secrets of people she hardly knows but absorbing them as her own. Apparently, it is not the actual people who are the artefacts on disply here, but Eloise’s obsession with them, which in turn manifests in their visibility. Once again, we are forced to reflect on the line between real and artificial – between theatre and life, and between the self and the performance of the self for an audience.

You must be logged in to post a comment.