© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Ballet

Ceremony of Innocence, The Age of Anxiety, Aeternum

London, Royal Opera House

7, 8 (mat) November 2014

Gallery of pictures by Dave Morgan

www.roh.org.uk

After honouring Frederick Ashton, its founder-choreographer, with a mixed bill of his ballets, the Royal Ballet has provided a platform for tried-and-tested present day talent: Kim Brandstrup, Liam Scarlett and Christopher Wheeldon. The programme was so underwhelming that I went twice in succession, to see whether alternative casts could make a difference.

Brandstrup’s Ceremony of Innocence uses mature dancers in the leading roles; first cast Edward Watson and Christina Arestis; second cast Bennet Gartside and Deirdre Chapman. Set to Benjamin Britten’s Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge (and created in 2013 for the Britten centenary), it proposes that an older man looks back at his youthful self, reflecting on what time has made of him. He could be Britten the composer or the ageing writer Aschenbach from Britten’s opera, Death in Venice.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

According to the programme note, the role of the principal woman is that of the man’s mother. Without that information, she would seem to be his wife. She is in varying states of distress at the loss of a son. He might have gone missing as a child playing at the seaside or been killed in wartime – or she has never accepted that her beloved boy has grown into a man. (Britten used to discard the youngsters he favoured once they grew up, wanting to preserve his illusion of innocent boyhood, his and theirs.)

It’s a somewhat complicated back-story that a second viewing helps in recognising the protagonist’s memories. He sits or stands aside, watching the ghosts of his childhood cavorting happily on the seashore. Leo Warner’s digitised wave effects tumble down the backdrop, which is sometimes a brick wall, a seaside promontory, a set of arches, a remembered location peopled by shadows.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

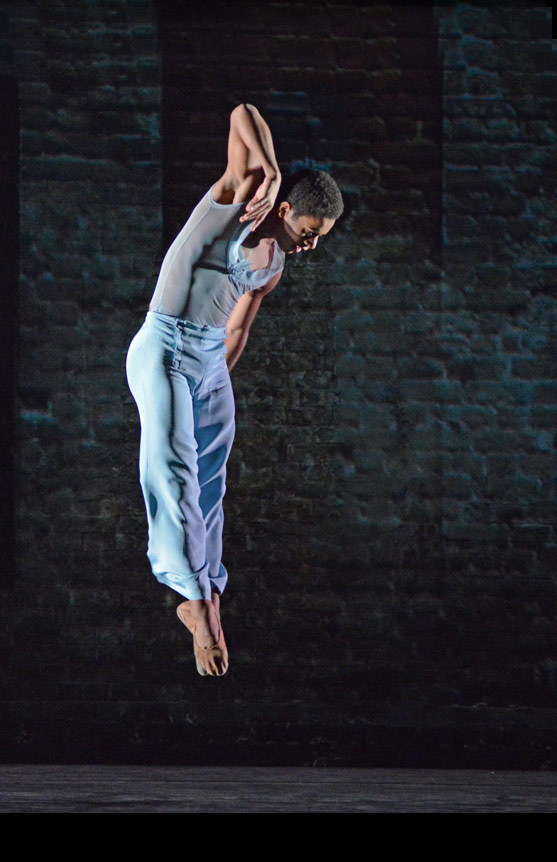

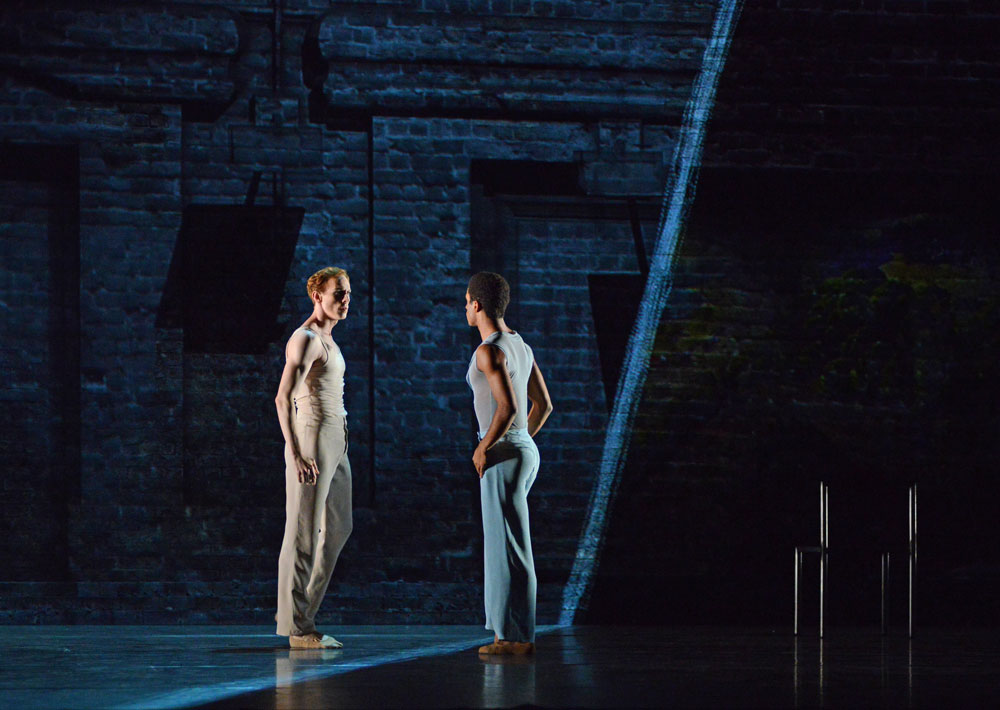

From the start, the woman is searching for her missing child. He appears, in the form of Marcelino Sambé or Paul Kay, bounding joyously among his playmates. The changing moods of Britten’s Variations determine alternating scenes between the exuberance of the boy, the anxiety of his mother as she refuses reassurance, and the elegiac recollections of the older man. Time shifts back and forth, including an encounter between the youth and his mature self as mirror image, startlingly lit by Jordan Tuinman as a gap in the space-time continuum.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Brandstrup’s choreography is very fine in the way the two central characters touch each other in gestures of consolation, regret, rejection, helpless inadequacy. He manages to vary the nuances of each pas de deux between the man and the woman, though there are too many duets, dictated by the music. He overuses swirling lifts and circular promenades on pointe for the mother, recurring each time she reappears. She is swung high over the shoulder of the older man and also that of her young son, which looks inappropriate (especially when he is much shorter than she is).

Arestis is striking as the agonised woman, her long legs extended into exclamations of despair. Chapman is more motherly in her concern, which reinforces the sense that her lovable boy (Kay) should behave more decorously with her. Sambé as the boy erupts into his scenes with such pent-up vigour that Watson, in character as his older ego, must surely be exaggerating memories of his vital younger self.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Yet when Watson finally gets a solo near the end, his arching arabesques reveal that the man mourning his lost creativity has always been exceptional – a glimpse denied to Gartside’s more mundane persona. We’ve had to take on trust all along that the central character is an artist of some kind. The promise of his younger self may not have been fulfilled, but wordless ballet can’t tell us that – nor why the woman is forever haunted. Ceremony of Innocence remains a crepuscular mediation on loss, its themes more interesting than its repetitive choreography.

In The Age of Anxiety, a world premiere, Liam Scarlett has taken on the challenge of W.H. Auden’s poem of that name. Four characters set out in search of the meaning of life or themselves (or something), getting drunk in order to blot out the misery of the war, the world (or something): rather more than ballet can handle. However, Leonard Bernstein’s 1949 Symphony no 2, inspired by Auden’s epic, is highly descriptive, concluding with an uplifting apotheosis in defiance of the work’s title. Jerome Robbins made a ballet to it in 1949, John Neumeier in 1979. Neither proved long-lived.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Scarlett has the benefit of dramatic sets by John Macfarlane and brilliant lighting by Jennifer Tipton: at last, we can see dancers’ faces. In order to follow the action, set in 1940s New York, reading the programme note, if not the book-length poem, is advisable. This narrative ballet, though, isn’t going to lead anywhere or stir any emotions.

Set in a lowish dive on 52nd Street, the story opens to a prelude of uneasy woodwinds. The first character to attract attention is a sinister bartender, probably a satanic figure. Three isolated drinkers are there already: Rosetta (Laura Morera or Sarah Lamb, a woman on the make; Quant (Bennet Gartside or Johannes Stepanek), a businessman; and Malin (Tristan Dyer or Federico Bonelli), a Canadian airman. A fourth person enters – Emble (Steven McRae or Alexander Campbell), a young naval recruit who bounces in like a sailor from Fancy Free (the Bernstein/Robbins ballet that became On the Town).

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

They make each other’s acquaintance while a GI and his girlfriend come into the bar. Emble picks a fight with the GI, proving he’s not to be taken at face value. Next to be noticed is apparently staid Quant, in an ill-fitting suit, who collapses to the floor after a brief solo. Inexplicably, the others pile on top of him as if in a Nijinska ballet. All four confront the barman in unison before he dopes them with alcohol and removes money from their wallets or pockets. Has he bought their souls?

He vanishes beneath an ominous Exit sign, after which they break into funky, but very balletic dancing. Drunk, they appear to be building up to an orgy to raucous music, bathed in a hellish red glow. A jazzy unison routine includes a mocking Hitler salute. The barman reappears and switches on a harsh white light, sobering them into leaving. They set out together, lost souls hailing cabs in vain, until they decide to walk to her apartment for yet more drink.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

Her place is oddly, lavishly furnished, with a view of the New York skyline. Is she rich or a kept woman? In Auden’s poem, she is a buyer for a department store. Morera portrays her as a lonely, brassy woman on the make; Lamb as a sophisticate slumming for rough trade, though she never stops being a ballerina. Sailor Emble is simply a sexy show-off; businessman Quant feels out of place but agrees to join in the ‘fun’. Airman Malin remains a dark horse. They dance an interminable jazz-ballet number that reveals nothing about their inner selves other than a desire to grasp any sexual opportunity, male or female.

McRae is more gee-whizz as Emble than Campbell, a plausibly boyish lout. Quant could be a dull character, but subtle Stepanek gives him a dapper, knowing air that makes him intriguing. All becomes clear when the intoxicated foursome link up to turn their backs, facing the skyline, and hands are placed covetously on bottoms and shoulders. Malin, the shy one, is revealed as gay, to no-one’s surprise. Dyer remains an introverted cypher, while Bonelli succeeds in bringing the troubled, haunted quality of film star Montgomery Clift.

© ROH, 2014. Photographed by Bill Cooper. (Click image for larger version)

Malin is given Bernstein’s thunderous apotheosis, during which he hurls himself around the stage, arms raised to claim the glittering skyscrapers of Manhattan as his own: ‘New York, New York, if I can make it there, I can make it anywhere.’ It’s an overblown ending to a banal ballet that can’t justify the portentous title it is trading off.

Wheeldon’s 2013 Aeternum, to Britten’s Sinfonia da Requiem, also ends with an apotheosis, aspiring to suggest a spiritual hereafter rather than a metropolitan ambition. Seeing Aeternum again, twice, reinforces my initial reaction that it’s glib, disguised by good performances and an overwhelming set of mobile wooden shards.

© Dave Morgan, by kind permission of the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The principal female role, taken by Marianela Nunez or Claire Calvert, appears in two guises. First, in a long dress, to the opening ‘Lacryma’, she is partnered by Death or his Messenger – either Nehemiah Kish, risibly melodramatic, or Eric Underwood, discreet. He puts his hand over her eyes, so in ballet terms she’s doomed or already in limbo.

She and fellow female spirits sit and raise one leg like a gun barrel, which is as crass a war reference as the Nazi salute in The Age of Anxiety. After a ‘Dies Irae’, set in some kind of inferno with Marcelino Sambé or James Hay as the Lord of Misrule, the heroine re-emerges in a brief white leotard, transfigured. She is joined by a second partner (Bonelli with Nunez, Ryoichi Hirano with Calvert), for a long pas de deux of redemption.

© ROH / Johan Persson, 2013. (Click image for larger version)

Set to Britten’s uplifting ‘Requiem Aeternam’, the pas de deux involves the man moulding and manipulating the woman in languorous unfoldings. What looks almost ethereal, were it not for the exposed sinews in the woman’s bare legs, involves the man handling her calf, knee, thigh, armpits, and hauling her upside down, signifying nothing in particular. Tremulously, she bourrées backwards, unsupported, only to be held by him, side by side, as they step into eternity. Wheeldon’s hommage to MacMillan’s Song of the Earth is blatant.

© ROH / Johan Persson, 2013. (Click image for larger version)

I was not persuaded that cast changes made a significant difference to the three ballets. Programme essays proposing profound meditations on the human condition went largely unrealised. Brandstrup’s Ceremony of Innocence is the more thoughtful of the two works to Britten’s music, though it verges on the obscure at a first viewing. The Age of Anxiety doesn’t bear a repeated visit, except to enjoy the wit of Stepanek’s supporting role in a misbegottten production. A dispiriting contemporary triple bill, alas, compared with the pleasure of the Ashton revivals.

You must be logged in to post a comment.