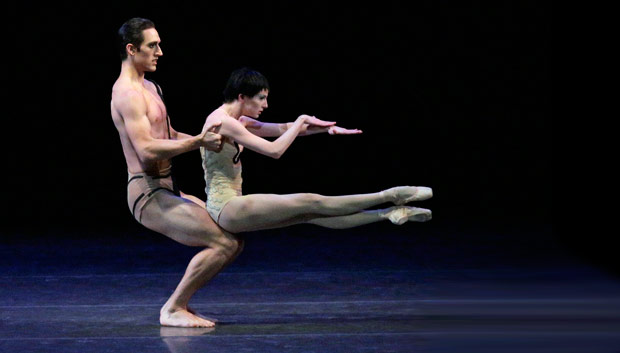

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

All Bach: Concerto Barocco, The Goldberg Variations

Hear the Dance – Russia: Symphonic Dances, The Cage, Andantino, Cortège Hongrois

New York, David H. Koch Theater

31 January – Bach, 1 February (mat) – Russia, 2015

www.nycballet.com

All Bach, All Russian

Like many companies of late, New York City Ballet has taken to assigning themes to its mixed bills. This season is full of them. Last night was “All Bach”; today’s matinée fell under the rubric “Hear the Dance: Russia.” One could see that the dances on each program had certain similarities. The responses to Bach tended toward the cerebral; those to Russian music were more effusive. There was far more fanfare in the latter program. The dancing on both days was strong. There is talent and dynamism across the ranks. Younger principals and soloists are breaking through into new roles. And the youngest corps-members, many of whom have been featured this season in Robbins’ “Goldberg Variations” and Peter Martins’ “Symphonic Dances,” are a particularly impressive bunch: musical, fleet, and assured.

The Goldberg Variations is back for the first time since the 2008 Robbins Celebration. It’s a stately, ingenious work, full of ideas, but over-long (he uses all the repeats in the music). It doesn’t have the powerful perfume and sense of time and place as Dances at a Gathering, which precedes it by two years. But in many ways, it’s more adventurous, even experimental. At times, Robbins seems to be testing just how far he can pare down the choreography without losing the audience’s interest. Some sections verge on minimalism. One consists almost exclusively of walking. In another two boys lie on the floor and daydream, lifting one leg, then another, one arm, a hand. Much attention is paid to transitions, almost as much as to the dances themselves.

Here, more than in Dances at a Gathering, the dancers play a version of themselves. They watch each other in relaxed poses and take turns dancing. Robbins plays with ideas about ballet: the way dancers imitate their teacher in class, the repetitions of small steps to the front, side, and back. He studies the mechanics of partnering, adding pliés and changing the arms, and complicates it further by pairing up partners of the same sex. (Quite novel at the time.) The choreography makes several nods to Balanchine: to the four-man opening of Agon, the swishing arm-movements from Concerto Barocco and the endless chains of dancers weaving in and out of complex figures. But mainly the ballet illustrates the music, faithfully, sensitively, even doggedly at times. The steps reflect every repetition, canon and fugue and the interplay of voices. It is most fitting that at the end, the dancers bow first to the pianist, who sits on a small platform to the left of the stage.

The ballet is a salute to Bach and the gracefulness and order of the Baroque. As it begins, two dancers (Faye Arthurs and Zachary Catazaro) walk on, dressed in an approximation of 18th century attire. With infinite delicacy and good manners, they perform a slow, courtly dance, bowing, crossing wrists, gesturing toward each other with decorative arm movements and soft elbows. As they recede, other dancers appear, wearing leotards with little skirts, tights. Later, as the ballet draws to its inevitable conclusion, the Baroque accouterments return, piece by piece. The original couple reappears, but now they’re the ones wearing rehearsal clothes. It’s as if the whole ballet and its Baroque details had been dreamed up by them.

Despite its excessive length, Goldberg is full of small pleasures. In this convincing cast, Lauren Lovette stood out for her charm, and Tiler Peck for the sheer brilliance and ease of her dancing in a bravura passage toward the end. She held her balances for an extra breath, then melted into effortless turns. Her performance elicited an eruption of applause. In a pas de deux with Jared Angle, Sterling Hyltin managed to stretch time, moving in slow motion to the accompaniment of fast music, then, as if at the flip of a switch, accelerating dramatically. She made it look as if these changes were out of her control. The pianist, Cameron Grant, played with his usual stylishness and clarity of tone, setting the mood for each piece while maintaining a sense of continuity from start to finish. In Goldberg, the pianist is the stand-in for Bach, the magician who conjures this whole world into existence.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

The program opened on a less promising note, with a somewhat subdued performance of Concerto Barocco, led by a mismatched pair: the serene, Brancusi-like Teresa Reichlen and Sara Mearns, a geyser of force and energy. Each is compelling on her own, but together their qualities clash: Reichlen recedes, Mearns overemphasizes. Their conversation is more like a series of nonsequiturs. In the pas de deux, full of floating lifts and repeated steps that unspool as if uttered on a single breath, Reichlen relaxed and expanded. Her arabesque is one of the loveliest things to be seen on the stage today: strong, un-forced, beaming outward into space. More generally, the performance lacked crispness, particularly in the first movement. The steps and the music didn’t merge into one.

All four of the ballets at the matinée on Feb. 1 were set to music by Russian composers: Rachmaninoff, Stravinsky, Tchaikovsky, Glazunov. The proceedings began with Peter Martins’ Symphonic Dances, originally made for Nikolaj Hübbe and last danced here in 2003. It’s a big, splashy piece, dusted with Russian flourishes. The beautiful, brightly-colored costumes are by Santo Loquasto. The ballet serves mainly as a showcase for the male lead, in this case the strikingly handsome Zachary Catazaro. Catazaro has been emerging, little by little, for several seasons. He’s not the greatest virtuoso in the company by any means, but he has a Romantic aura and the ability to convey drama without looking like he’s trying too hard. The opening, in which he leaps and skates across the stage in great space-devouring jumps, or slides one leg along the floor while glancing back at the audience – as Rachmaninoff’s chords crash all around – is both exciting and sexy. Catazaro rose to the occasion. He was backed by an excellent quartet of young male dancers: Harrison Ball, Joseph Gordon, Spartak Hoxha, and Peter Walker. All of them seem destined for bright futures in the company. The entire ballet has a distinctly male energy – the pas de deux and female ensembles are less inspired.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

After the Martins came two works by Robbins (The Cage and Andantino, the latter a pretty trifle) and a splashy closer by Balanchine: Cortège Hongrois. Sterling Hyltin makes a fantastic “novice” in Robbins’ bizarre feminine revenge-drama, The Cage: a twisted tangle of prickly limbs and inverted posture. At one point she flopped from a tight position on pointe to the floor so violently and fast it looked as if she might never get up again. Her tussle with her male victim – Justin Peck, convincingly cave-man-like – was both erotic and brutal. And yet Hyltin also managed to convey the characters’ animal nature, the mindlessness behind the violence. The wild-wigged all-female ensemble – denizens of this strange tribe of man-killers – danced with a kind of gleeful abandon, led by its high-kicking, glamorous queen, Emily Kikta. Incongruously, this orgy of sex and violence was followed by Andantino, a swoony pas de deux danced with appealing lightness of touch by Ashley Bouder and an attentive Andrew Veyette.

Then came the party: Cortège Hongrois. Balanchine cobbled together this suite out of dances from Petipa’s Raymonda, an evening-length ballet with festive music by Alexander Glazounov. There are two teams of dancers, one wearing laced-up booties and long skirts – the men are in ridiculous puffy green jackets – and festooned with ribbons, the other dolled up in white tutus trimmed with gold. The two troupes enter together, then perform alternating numbers. Georgina Pazcoguin and Craig Hall led the czardas, kicking and stomping, swirling and leaping to their knees. Maria Kowroski and Russell Janzen were the king and queen of the aristocratic crew in white. The ballet isn’t terribly deep, but it has its share of lovely solos, the first of which was executed with great polish by Brittany Pollack. The big czardas was over-the-top, almost tongue-in-cheek. In the famous slow, exotic solo, accompanied by a sinuous melody on the piano, Kowroski was fairly bland. She didn’t bend or twist nearly enough, or hover in the pauses to create suspense, or tilt her body to make it look as if she were being pulled back in space by an external force. It’s a shame, but I guess exoticism just isn’t really City Ballet’s thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.