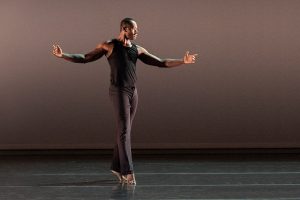

© Alejandro Gomez. (Click image for larger version)

Ballet San Jose (in transition to Silicon Valley Ballet)

Bodies of Technology: This Might Be True, Eighty One, User’s Manual

San Jose, California Theatre

28 March 2015

www.balletsj.org

sanjosetheaters.org

Ballet San Jose is full of surprises this evening. First comes the announcement that the company has exceeded its “Bridge to the Future” fundraising goal. Just a few weeks ago it wasn’t clear whether tonight’s performance would even take place and now the rest of the season is assured, with money left over. That said a new hurdle looms in October when 3.5 million dollars is needed for the fall season plus administrative and financial restructuring.

Then Alan Hineline, BSJ CEO, and Board of Trustees Chair, Millicent Powers, unveil the troupe’s new name and logo. Since its beginning in 1986, the name has changed several times: originally it was a joint venture with Dennis Nahat’s Cleveland Ballet and was christened the San Jose Cleveland Ballet, splitting its seasons between the two cities; with the Ohio company’s demise in 2000 the new name was Ballet San Jose Silicon Valley, only to drop the Silicon Valley in 2006; the latest re-dubbing is Silicon Valley Ballet, perhaps in a branding move to attract more funding from the ultra-wealthy technology industry in the area or to distance it from the recent years of decline. However it’s not clear when the new branding goes live and on the web they still use Ballet San Jose in most places.

© Alejandro Gomez. (Click image for larger version)

Nomenclature and finances aside, the artistic direction of this company is also of interest. In 2011, Nahat was forced out after twenty-five years at the helm (not counting the eleven years as founder/director of Cleveland Ballet). Wes Chapman, former principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre and artistic director of Alabama Ballet, was brought in as artistic consultant while the search for a permanent leader continued. The company was already leaning toward looking like a “satellite” company of ABT when José Manuel Carreño, another former principal dancer with ABT, took over as artistic director in September 2013, and the lean became more pronounced. But that doesn’t mean it slavishly follows ABT in all respects.

The first program of this season, “MasterPieces”, shown in February, accurately reflected its name with Balanchine’s Theme and Variations, Robbin’s Fancy Free, and Twyla Tharp’s In the Upper Room. All of these works have longevity, created in 1947, 1944 and 1986 respectively, and are long-standing staples in the ABT repertoire as well as in those of many other international companies. This second program, “Bodies of Technology”, is a bird of a radically different feather and nothing to do with ABT. Two of the works are world premieres (one by the local Amy Seiwert, the other by former local Yuri Zhukov) and the third, by New York-based Jessica Lang, dates from 2013.

© Alejandro Gomez. (Click image for larger version)

Seiwert’s This Might BeTrue employs an absorbing computerized interactive background projection by media designer Frieder Weiss from Berlin, with whom Seiwert collaborated several years ago for a work commissioned by the San Francisco International Arts Festival. From the blue and white geometric Mondrian patterns that frame the dancers and move with them, to ripples of dark and light radiating in all directions as a reaction to the dancers’ movement, to tiny bubbles like those in sea-foam on a beach or in a glass of champagne, the immense size of the virtual backdrop dwarfs the dancers both physically and artistically. The dancers turn in solid performances, notably Grace-Anne Powers, but the choreography, all too recognisably in Seiwert’s usual vein, grows repetitious without rising to the challenge of engaging the interactive possibilities in an insightful manner. Integrating technology to reveal some aspects of its effect on our lives could have more impact than simply using it as window dressing.

In the time since Lang’s Eighty One made its debut two years ago, the dancers have made it their own. The inherent clarity and simplicity of the choreography shines through, where previously it looked a bit muddled. The technology used here is in the creation of the music on an instrument made and “played” by composer Jakub Ciupinski live on stage. In effect, he has put two theremins together in a way that lets him drive an electronic score while watching the movements of the dancers. Fascinating stuff for a ballet company, Merce Cunningham and his composer/musicians (e.g. John Cage, David Tudor, Takehisa Kosugi, etc.) had been doing this kind electronic improvisational sound accompaniment since the 1940s although they weren’t interested in connecting it with the dancing. (For specific details see this MetroActive article, “Jakub Ciupinski creates a strange collaboration with Ballet San Jose”)

© Robert Shomler. (Click image for larger version)

Local audiences are more familiar with Zhukov’s choreography for his own company, Zhukov Dance Theatre, with its hand-picked dancers of top quality, whose talent for modern idioms is perfect for his ideas. Working with the more classically-based and larger Ballet San Jose, means altered expectations for both creator and spectator and he does not disappoint this reviewer, or the crowd to judge by their enthusiastic applause.

The lone life-sized white porcelain figurine of an 18th century lady stands in a pool of light as Zhukov’s User’s Manual begins. The ghostly Madame de Pompadour character, complete with powdered wig and panniered gown, is not human, but an automaton. As she moves stiltedly, the whirr of the gears beneath the facade is almost audible.

Western culture has had a fascination with robots or mechanical facsimiles for centuries, from Leonardo da Vinci’s amour-clad mechanical knight in 1495, through to pop culture icons R2D2 and 3CPO in Star Wars and the replicants in Blade Runner. In classical ballet there are the doll in Coppélia and Drosselmeyer’s creations in Nutcracker. Most of them are objects of affection or curiosity. But in this ballet the story shifts to a darker place.

© Francisco Preciado. (Click image for larger version)

As the ornate robot rotates, sits down and stands up, moves her hands and arms and drifts toward the wings, a woman crawls out from under the back curtain. Wearing gray shorts and ivory top, with an auburn wig cut in a Clara Bow bob, she has a very sharp contemporary edginess about her. Then she is joined by three men. After Madame de Pompadour exits, seven more identical dancer clones appear as if they are today’s version of what an automaton should look like.

The piece progresses with group sections, a pas de deux and full company ending. Somehow the identically-costumed women have a chilling effect as they lose all individual identity. During the performance, ten panels, high up across the back of the stage, change from projections of machine innards to video testimonials of what appear to be real people – or are they? While it is given that the dancers are just dancers, are the beings they portray people who have lost their humanity, as the Daleks in Doctor Who, or are they merely machines, manufactured by someone or something?

In spite of being a bit too long, this ballet provokes much thought about our current society. Just look around at the audience, cell phones reluctantly pocketed as the performance starts and popping out the instant the intermission begins. The gigantic tech firms, located within a twenty-mile radius of the theater are more interested in putting their money into more technology instead of the arts, one of life’s most important elements, that enriches our humanness and gives us hope in the face of the tech monolith.

You must be logged in to post a comment.