© Kevin Yatarola. (Click image for larger version)

Noche Flamenca

Cambio de Tercio (Shiftin Ground)

New York, Joe’s Pub

8 April 2015

wwww.soledadbarrioandnocheflamenca.com

www.publictheater.org/en/Joes-Pub-at-the-Public

Olga Pericet

Flamenco Sin Título

New York, Repertorio Español

9 April 2015

www.olgapericet.com

www.repertorio.org

Flamenco Feeling

Flamenco has diversified so much in the last few decades that one often has no idea what one is going to get. Whether a show appeals or not depends largely on expectations. This week, two of its many manifestations are on display in New York: Joe’s Pub presents the bare-bones tablao format of Noche Flamenca (a company based in New York) and Repertorio Español offers an intimate one-woman evening by Olga Pericet, well-known in Spain but relatively new to New York. The contrast in approach and presentation is striking. Both are intermittently engrossing. Each inspires a different kind of enjoyment.

The stage at Joe’s Pub is dinner-plate sized and awkwardly shaped (a triangle), allowing space for only a musician or two and, at the most, three dancers, as long as they don’t move around very much. Luckily, flamenco can be as spatially-contained or wide-ranging as the situation allows. There’s something thrilling about sitting within spitting distance of the dancers: you feel their energy in your chest and follow the shifting moods in their eyes. This is especially true when Soledad Barrio, Noche Flamenca’s star, is on the stage. Everyone’s attention is rapt: the musicians, the singers, the audience. At one point in her Soleá – a solemn, urgent song-style – Barrio’s eyes became vacant, and her body seemed to dance without her volition, legs flying, body traveling across the stage in a cross between a stomp and a glide. I wondered, “where has she gone to?” Barrio isn’t pretty when she dances: her compact body becomes a weird mix of angles, and her expression is hard, like that of a Revolutionary at the barricades, a Goyaesque character transported to our times.

© Kevin Yatarola. (Click image for larger version)

Nothing else in the evening quite measured up to this moment; a few felt like filler, though, to be fair, the show, which is repeated twice daily, is bound to be different every time. The three-woman ensemble was polished but constrained by the space and the often generic choreography (though I enjoyed Xianix Barrera, who injected a healthy dose of teasing sensuality). The trio’s finest moment was a playful folk song (a bulerías) about a cigarette-paper seller. The dancers joined the singer (Emilio Florido) in an a-cappella rendition of the song, complemented by footwork and clapping. (Flamenco is often so relentlessly serious that lighter moments like this, evoking the town square, are a welcome relief.)

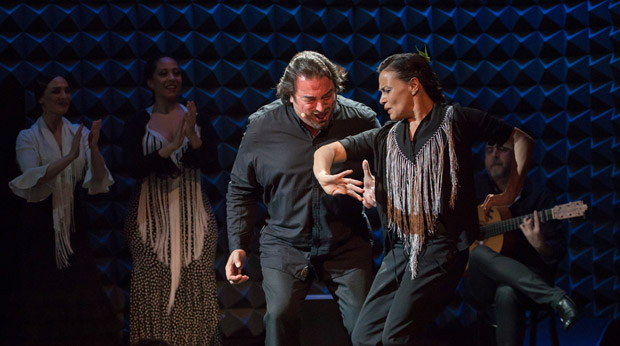

The other soloist, Juan Ogalla, performed a farruca, a fierce, masculine song-style characterized by fast rhythmic footwork. Ogalla has a tendency to over-project; he wears one expression, fierce and angst-ridden, throughout. His dancing, too, can be rather one-note – hyper-virile, with an emphasis on lunges in profile and fast swivels. But he comes into his own in the fast zapateado, throwing off kicks and one-footed hops with panache and shaping the sound of his taps and stomps with vivid phrasing and accents.

For all their adherence to tradition, the artistic minds behind Noche Flamenca (Martín Santangelo and Barrio) are not averse to experimentation. A few of the numbers at Joe’s Pub featured an electric bassist (Hamed Traore); in one, a hip hop dancer (David Thomas) challenged Ogalla to a dance battle. What’s appealing about these collaborations is that they feel organic. From the start, Traore and Thomas are full members of the ensemble; they clap and sing in the opening chant and return periodically throughout the evening. They’re a part of the family rather than guests or exemplars of an alien artform. In fact, the bass adds a pleasing harmonic element to the songs; it doesn’t sound out of place. The “battle” between hip hop and flamenco is less convincing, but Thomas is a compelling performer in his own right; his bird-like arms and slides across the stage have their own poetry. The two dancers are earnest in their attempts to riff off of each other, but neither dance feels enriched in the process.

© Michael Palma. (Click image for larger version)

Olga Pericet’s show at the Repertorio Español, Flamenco sin Título (Untitled Flamenco) is rather more ambitious, less improvised, more artfully conceived. It falls into a category I think of as art-flamenco, in which every esthetic detail has been carefully considered, from the dancer’s wardrobe to the lighting to the placement of the musicians on the stage. Even entrances and exits, through a black curtain at the rear of the stage, are subtly orchestrated. A lamp hangs from above, casting a pool of glowing light over the two singers (José Ángel Carmona Manzano and Ismael Fernandez), the guitarist (Antonia Jiménez Arenas), and Pericet. The three musicians are dressed identically in black suits and white shirts. (Anomalously, the guitarist is a woman, though no attention is called to this.) The feeling is intimate, sober, and serious.

Within this elegantly simple set-up, Pericet is a mercurial figure. She is diminutive, with a supple frame, beautiful oval face and sparkling eyes, which she flashes playfully (often flirtatiously) at the audience. Unlike Barrio, she is an unabashedly presentational performer; her dances are displays, flowers tossed to the public rather than inward trajectories. (At the end of one piece, she tosses an actual flower into the theatre.) Some of these displays are quite wonderful. Pericet’s repertory ranges beyond flamenco to escuela bolera – folk dances using castanets, the long bata de cola, and mantón, or fringed shawl). Her mantón dance (a cantiñas), all flying fringe and ruffles and swirls of movement, was a delight. The enormous red shawl seemed to engulf her completely as she flung, folded, swirled and wrapped it around her. The same was true of her dance in the bata de cola; here the train of her dress became a dragon’s tail, augmenting the lissome curlicues of her arms and arching shape of her back. (The dress was one of the most beautiful I’ve seen, trimmed with sari-like details.)

© Michael Palma. (Click image for larger version)

But Pericet wasn’t able to maintain this level of intensity in other numbers. Her rhythmic footwork isn’t as precise or quick as some. Her coy glances and hip shakes can feel cloying. Two baroque-style dances (which she calls esoñaciones, or fantasies) showed off her clean, flickering port de bras and delicate leg movements, but felt out of place, disconnected from the rest. (They were performed to recorded music.) Such distractions were compensated for in some measure by the uniformly high level and interest of the music-making. The two vocalists sometimes sang in harmony – something I’ve seldom, if ever, heard. One of the high points was purely musical: a trio for guitar, mandola (or Spanish mandolin, played by Manzano), voice, and palmas. The three musicians sat facing in each other like Quakers at a prayer meeting, practically knee to knee, engaging in a sensitive, intimate conversation. Time stood still.

In both shows, the most exciting element was the push-and-pull between the music-making and the dancing. Guitar, rhythmic clapping, the human voice, full-bodied movement, and footwork – all come into play. And because of this, when everything is right, flamenco is still one of the most complete human expressions, one that engages the ear, the heart, and the eye. But, like duende – the mythical spirit that ignites flamenco dance – such moments of complete fusion are elusive.

You must be logged in to post a comment.