© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

Walpurgisnacht Ballet, Sonatine, La Valse, Symphony in C

New York, David H. Koch Theater

10 and 15 May 2015

www.nycballet.com

Soirée Française

After a week of modernist works by Balanchine set mostly to Stravinsky, Hindemith, Webern, there’s no denying that a night of French music falls sweetly on the ear. New York City Ballet’s French program is a musical feast: ballet music from Gounod’s Faust, two Ravel pieces, and, as a closer, Bizet’s ebullient Symphony in C, written when the composer was only seventeen.

French music had a heady effect on Balanchine. He responded to its vivid colors, its strong sense of atmosphere and mood. La Valse contains bewitching mix of decadence, cruelty and doom; Sonatine is a poem on the theme of insouciance and civilized collaboration. Walpurgisnacht Ballet, originally made for the Paris Opera (as part of a production of Faust) is theatrical and operatic, while at the same time poking fun at these very qualities. Symphony in C also began life as a French ballet – Balanchine made its predecessor, Le Palais de Cristal in Paris in 1947, the same year he created Theme and Variations in New York. In its vivid display of liquid geometries, it is the balletic equivalent of a fountain at Versailles.

Presented together as they are here, they form perhaps too rich a meal, but who can complain about a little excess from time to time? Sonatine, a pas de deux created as an opener for the 1975 Ravel Festival, is the most delicate and the most infrequently performed. It was last seen here over a decade ago. The original interpreters were Violette Verdy and Jean-Pierre Bonnefoux, both French, both stylish and, in the case of Verdy, highly spiced. The steps – little kicks and tilts on pointe, amicable walkabouts, staccato jumps, folksy toe taps – communicate a kind of playful but adult good humor. (In its form and style, it is related to both Duo Concertant, from 1972, and Jerome Robbins’ Other Dances, from 1976.)

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

I caught two casts, on May 10 and 15. (Elaine Chelton played the Ravel sonata, onstage, on both occasions, with great clarity; perhaps a more lilting, warmer sound might have added a greater atmosphere.) In the earlier performance, Tiler Peck danced with Joaquín de Luz; in the latter, Ashley Bouder was paired with Gonzalo García. Peck danced it with her usual fluidity and a kind of voluptuous ease; she stressed the twist in her shoulders and hips and played with the rhythms, adding a slight syncopation to some of the steps. For his part, De Luz dug into the Mazurka-like choreography and made much of the few passages of virtuosity while maintaining his characteristic cheerful demeanor. But there was little rapport between them, and the intimate feeling of promenading together on the boulevard on a sunny afternoon was diminished. Bouder and García were even more mis-matched. Bouder tended to over-power the choreography, playing it for the audience rather than for herself or her partner. García’s dancing was soft-focus. It’s a charming and delicately-perfumed ballet but at the moment the chemistry isn’t quite right.

Sara Mearns’s turn in Walpurgisnacht (May 10) felt momentous: grand, authoritative, regally-paced. The lush melody of the pas de deux allowed her to expand to her most radiant, slowly unfurling each limb for the admiration of the audience. The other passages for the ballerina are pure bravura: diagonals of beaten jumps, hops on pointe, turns that accelerate into a blur, all of which she accomplished with ease, as if finding pleasure in each step. At all times, her face remains completely lucid, in the present. The old-fashioned opulence of the score suits Mearns; she is a ballerina in the grand (old) style. In contrast, Teresa Reichlen, débuting on May 15, made the steps look a little too easy; she didn’t push them to full effect. In the ensemble sections – particularly the gypsy-like “Danse Antique” – the corps danced with gusto and verve. The ballet ends with a rousing storm; the women spin wildly with their hair – now un-fastened – flying every which way. Completely over the top and delightful.

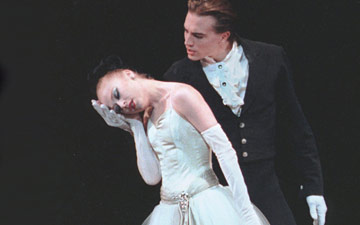

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

La Valse and Symphony in C are more regularly performed. In Sterling Hyltin, the company has its most feverish waltzing debutante, diving heedlessly into the arms of her mysterious, and soon deadly, suitor in La Valse. (She’s currently dancing the Sylph in La Sylphide as well; her ability to slip into character is one of her most impressive qualities.) Amar Ramasar plays the role of the dark stranger with the flair of a silent-movie villain, maliciously pointing his toes and commanding his victim with a petulantly upturned chin. (Justin Peck, last season, played it with a more brutal edge.)

These days, in Symphony in C, Maria Kowroski is the dancer most closely identified with the sinuous, sustained second movement. Her height and the extraordinary length of her limbs – combined with her absorbed demeanor – add to the sweep of the choreography’s many swoons and dives. Kowroski seems to float on the gleaming surface of the music. However, her footwork in the fugue-like sections could be more rhythmically-acute. All in all, the company dances a happy, crisp Symphony in C – Ashly Isaacs and Joseph Gordon were particularly incisive in the buoyant third movement on May 15 – but not a transcendent one. For that, it would need a little more softness, more generosity in the upper body to contrast the sharpness of the arms and legs.

Style, wit, femininity, sparkle: these are all ingredients of Balanchine’s France. There are not many better ways to spend an evening.

You must be logged in to post a comment.