© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

New York, David H. Koch Theater

4 June May 2015

www.nycballet.com

Fairy Queen

George Balanchine’s Midsummer Night’s Dream is really two ballets, layered one upon the other. In the first the choreographer tells the intertwined stories of three couples, two of them human and one composed of fairy royalty. (Oberon and Titania, king and queen of the fairies, tussle over the ownership of a little pageboy, setting the ballet in motion.) By the second act, the couples’ entanglements have been successfully resolved, with great effort and after much shedding of tears. Now, Balanchine presents a formal entertainment. It begins as a wedding ceremony, accompanied by Felix Mendelssohn’s famous march. Then, after some courtly ensembles, the ballet introduces a fourth couple. The guests’ identity is a mystery – in the program they are listed simply as the “divertissement” couple.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

As happens so often in ballet, abstraction follows narrative. Through this couple, Balanchine appears to be offering up an image of harmonious partnership, that elusive ideal. Petty conflicts melt away, along with all the cares of this world. To a gossamer, Mozartean melody for the violin (from a Mendelssohn string symphony) the man assists the woman, almost invisibly, allowing her to skim the stage, tapping her legs in the air, or turn, endlessly and calmly, on her axis, sometimes reversing direction mid-stream. In the final moments, he gives her a gentle push and she tips over, softly and without fear, into space. In that moment, we see grandeur without ego, trust without need.

It is the moment that most clearly illustrates the difference between Frederick Ashton’s interpretation of the Shakespearean farce and Balanchine’s. Ashton closed his 1964 ballet with a pas de deux of almost erotic uninhibitedness, danced by the story’s main characters (Oberon and Titania). Two years earlier, Balanchine had opted, instead, to take a step back, distilling the ballet’s emotions into pure form.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Which is not to say that he wasn’t interested in telling a story. One of the great pleasures of this Midsummer, the final work in New York City Ballet’s spring season, is the clarity, speed, and economy with which the story, with all its moving parts, unfolds. Episodes are spliced together with cinematic fluidity. Blackouts and dissolves transport the audience from one part of the forest to another, so that it can witness events taking place simultaneously. (Mendelssohn’s descriptive music helps.) The confusion wrought by the fairy king, Oberon, and his mischievous sprite, Puck, reaches its climax in a scene of controlled chaos in which every character seems to traverse the stage at once. Then, just as quickly, order is restored.

Nor does abstraction have the final word. After a magical dissolve, in which the courtly ballroom of the second act once again becomes a forest glade, a cloud of twirling, flapping bugs – tiny students from the School of American Ballet – floods the stage, as it did at the beginning. They are the last image we see.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

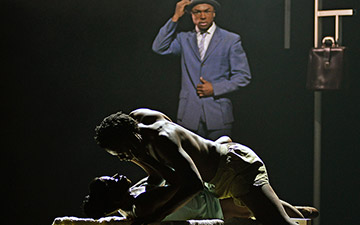

Magic, love, comedy, all rolled up into one. The cast on June 4 contained several débuts, including Daniel Ulbricht as Oberon. He has the elevation and the speed for the part, but as yet neither the elongation nor the clarity of footwork. Edward Villella, who created the role, has said that Balanchine cast him as Oberon in order to turn him into a prince, and he rose to the occasion. Ulbricht, an affable, earthy dancer, has yet to make the transition. Sterling Hyltin and Amar Ramasar, débuting as the divertissement couple, were resplendent; Hyltin’s ability to shape movement, concealing the mechanics behind it, is one of her supreme talents, as is her courage: her dancing is never timid. With the aid Ramasar’s elegant, unobtrusive partnering, she unfolded into one limpid shape after another with ease and charm. Ramasar danced with musicality and joy.

Ashley Isaacs, a member of the corps (but not for long, I’d wager) conquered the role of the high-flying Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons, with her usual attack and authority. Already, she presents herself like the principal dancer she may one day become. The hapless lovers were played by Brittany Pollack, Ashley Laracey, Russell Janzen, and Zachary Catazaro. Pollack and Janzen were new to their roles. All four exhibited excellent comic timing and tiny details of characterization that brought the story alive. I’ve seldom seen as dreamy and sweet a Lysander as Russell Janzen. (He and Laracey made an effectively moony couple, just shy of smugness.) Troy Schumacher’s Puck was sprightly and quick, without resorting to cuteness.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Presiding over this motley assortment was Teresa Reichlen, tall, radiant and oh-so-slightly ironic in the role of Titania, queen of the fairies. It’s no wonder Oberon has to resort to all sorts of trickery and magic to get his way. She is unflappable, even in anger. Reichlen’s solo with the hapless Bottom – transformed, by Puck, into an ass – was all glowing benevolence, transmitted by the softness of her movements. In the otherwise generic pas de deux with her nameless cavalier (Justin Peck), she landed in his arms, on her knees, as if alighting on a pillow.

The orchestra had its rough moments; a squawk in the woodwinds provoked a few snickers in the audience. The overture was very fast, and overly loud. But none of this could spoil the evening. Midsummer is the ideal way to start off the summer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.