© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The Royal Ballet

The Dream, Song of the Earth

New York, David H. Koch Theater

24 June 2015

www.roh.org.uk

Royal Visit

After an absence of eleven years, the Royal Ballet has finally returned to New York; they’re currently presenting two programs at the Koch Theatre, where they are being presented by the Joyce Theatre Foundation. It’s a huge undertaking for the Joyce; as the Wall Street Journal pointed out this week, it’s also a bit of a gamble, financially speaking. It’s dispiriting to consider how prohibitively expensive such tours have become; there was a time, in the sixties, when the company visited almost every other year.

All of which makes this visit particularly welcome. The company has come with two mixed bills composed almost exclusively of British ballets. The first is a double bill of works from the sixties: Frederick Ashton’s The Dream (1964) and Kenneth MacMillan’s Song of the Earth (1965). Ashton’s ballet tells a concise story, drawn from Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream; MacMillan’s is an almost abstract interpretation of a Mahler song-cycle based on a series of ancient Chinese poems about youth, loneliness, love and death. Both works are central to the company’s identity.

© Johan Persson, ROH. (Click image for larger version)

New York audiences are already familiar with The Dream from frequent revivals at American Ballet Theatre. It’s a delightful ballet, no matter who performs it: full of witty steps and pretty stage pictures and wonderfully musical. A favorite effect is the way the fairies freeze at the end of each phrase during the overture. Another is the fairies’ hop-hop-lunge sequence, timed perfectly to fit a three-note figure in the music. There are many, many others. (The score, which consists of incidental music by Felix Mendelssohn, was played at a leisurely tempo by the New York City Ballet orchestra under the baton of Barry Wordsworth, the Royal’s Music Director.)

It’s intriguing to see subtle differences in how the two companies approach the ballet. ABT’s version is more sharply-timed and tongue-in-cheek, while the Royal Ballet dancers play their roles more naturalistically. At ABT, Puck is mysterious, creature-like; the Royal’s interpretation is more playfully boyish. The young couples are less cartoonish in the Royal’s version; the rustics are more broad. The lighting in the Royal’s staging has an eerie glow that enhances the feeling of depth and gives the whole scene a more magical atmosphere. A children’s chorus, the Brooklyn Youth Chorus, sang the choral sections; the pure, silvery timbre of their young voices worked well.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

At the June 24 performance Sarah Lamb and Steven McRae were Titania and Oberon, queen and king of the fairies. James Hay danced the role of Puck; Bennet Gartside was a wonderfully goofy Bottom. (That’s the rustic fellow who falls under Oberon’s spell and prances around on pointe while wearing the head of an ass.) Lamb was supple and precise, but rather restrained as Titania, neither as imperious nor as touchingly silly as Ashton’s character can be. McRae, an extraordinarily light, small, and fast dancer, was dazzling, particularly in the scherzo, where his spins accelerated to such a blinding speed that it seemed he might levitate, like a helicopter. The music at that moment evokes a gathering storm, another example of Ashton’s knack for finding the right visual counterpart for a musical idea. The final pas de deux, though, lacked the erotic frisson that can make this dance such a powerful evocation of marital reconciliation. Lamb’s shoulders and hips trembled, but the feeling of rekindled passion was missing.

© Bill Cooper, ROH. (Click image for larger version)

This was my first time seeing Song of the Earth; on first viewing I found it rather drawn-out and choreographically thin. Perhaps a second performance will allow me to see more. The six Mahler songs from Das Lied von der Erde to which it is set are based on Chinese poems, translated into German. These were sung by two onstage vocalists, Katharine Goeldner, a mezzo, and Thomas Randle, a tenor. Unfortunately Mr. Randle sounded quite strained. The dances allude subtly to the texts. At times, the steps have a slightly “eastern” look: flexed feet, decorative gestures for the arms, flat-footed shuffling reminiscent of Chinese opera.

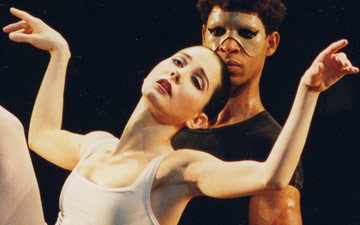

The designs are spare: a dark grey backdrop and wings, plain leotard dresses in white and gray for the women, tights and plain white tops for the men. There are three central figures: an unnamed woman, danced here by Marianela Nuñez; a man in white, Nehemiah Kish; and a man in black wearing a half-mask, listed as the Messenger of Death. The latter was danced by the company’s Cuban star, Carlos Acosta. The cast also includes an ensemble of sixteen.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The first dance is for the men, who mimic and partner each other. (The song speaks of drinking as a way to forget death.) The second begins as a reverie for the women; one (Nuñez) stands apart from the others, bourréing forward and back as Death looks on. In the third, four men and four women kneel and sway, as if playing a game (the song alludes to young people at a tea pavilion). A woman (Yuhui Choe) is lifted up and carried through the air like a bird. The fourth is a dance for seven couples; it has a lovely theme of legs rocking like a pendulum. The fifth is a drunken frolic for the men; death joins in the fun. And then, finally, comes the final song, the longest of them all, sung by the mezzo soprano. There is a sense of forboding and loss. The dancers sway side to side, as if in mourning. The central woman is pulled between one man (a lover) and Death. The three are locked in a perfectly balanced trio — at the end of the ballet, they seem to walk into eternity together. The singer repeats the word ewig, or forever, over and over as the dancers walk forward, rising and falling, rising and falling.

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

The ideas are poetic, the atmosphere melancholy. On this night, the dancing was limpid, beautiful and reserved. Nuñez, in particular, is a dancer of touching purity; nothing is exaggerated for effect. Even her stillness is compelling. At 42, Acosta still emanates a larger-than-life presence; his hands, in particular, have a kind of shamanic power. Kish’s dancing is elegant and lyrical. But the cast’s excellence couldn’t disguise the relative thinness of the choreographic text and its stop-and-go phrasing, so at odds with the sumptuous phrasing of the songs. As a result, the overall effect was more decorative than profound.

Perhaps, as I said, I’ll see more the second time around. Some dances are like that. Either way, it’s good to have these dancers in town.

You must be logged in to post a comment.