© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

Paloma Herrera: Back in BA

I had never thought about it before, but in many ways Paloma Herrera is the classic porteña – a word that refers to a person born in Buenos Aires: chic, voluble, friendly, and completely in her element sitting at a table outside the elegant Museo de Arte Decorativo on the broad, tree-lined Avenida del Libertador. When I caught up with her in July, it was one of those unbelievably mild winter afternoons where all you want to do is while away the hours at a café in the sun. Herrera strode in, her long, perfectly straight, black hair pulled back from an animated face. She was back in Buenos Aires for a few days between teaching jobs.

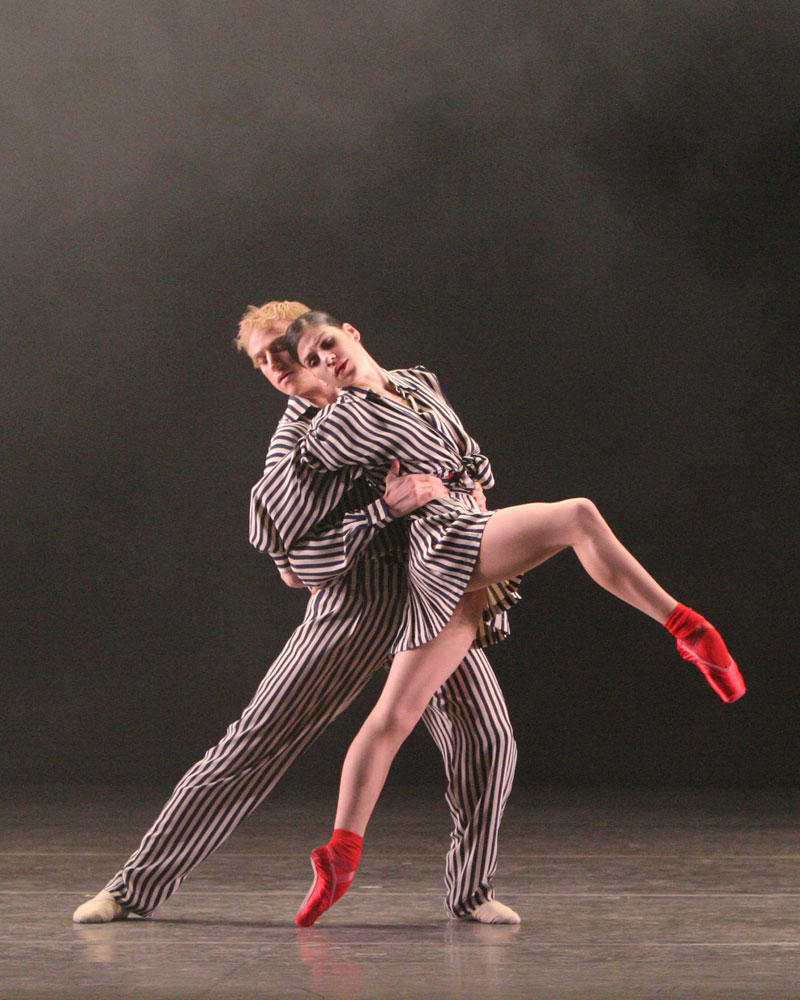

Two months earlier, in late May, Herrera had retired from American Ballet, the company she had danced with for almost a quarter century. Her last farewell performance was a Giselle with Roberto Bolle, which she danced impeccably as always, with the pure, unmannered style – Herrera has never been one to take shortcuts or gild the lily – and crisp musicality for which she is known. Always a paragon of classicism, she has impressed me even more in a surprising range of roles: as the opening ballerina in Balanchine’s Symphony in C – all those crisp tendus! – and as the lady with the red purse in Jerome Robbins’ Fancy Free – a ballet that brought out her sass – or as one of the impassive amazons in Merce Cunningham’s Duets. Or in anything by Twyla Tharp.

© Marina Harss. (Click image for larger version)

We sat down to talk about her training and career, about moving back to Buenos Aires, and about what she thinks has changed in the world of ballet and in the wider culture. What follows are highlights of our conversation, translated and slightly edited. The clarifications in brackets are my own.]

So you’re in the process moving your home base to Buenos Aires. Is it a big change for you?

I love New York and the life I have there, but I always had a foot here. So the change hasn’t been so abrupt. My partner is here. Now my life can be a little more laid back, more settled.

What are your near-term plans?

I want to finish out the year well. I have some shows here in Buenos Aires and a tour around Argentina. I’ll be dancing Cranko’s Onegin at the Teatro Colón and then Giselle in Rosario and Mendoza, and before that I have performances in Corrientes and Uruguay. I’ll be dancing with Juan Pablo Ledo [of the Ballet Estable del Teatro Colón]; he was my partner in Giselle last year. Lidia Segni [then the director of the Colón] asked me if I wouldn’t like to dance with someone from the company, since I had a little more time to prepare. It was a great experience. He’s a very good partner, but more than that, he likes to work and he has the same values, the same ethics, as I do. My final performance will be at the Teatro Argentino de La Plata at the end of November. And in December I turn forty.

What is your relationship with the Teatro Colón like?

I’ve danced under every administration and I never had a problem with anyone. I have very basic needs: I just need my studio and my teacher. I do my thing. I don’t give opinions and I stay on the sidelines. So I’ve had excellent relations with everyone.

© Hidemi Seto. (Click image for larger version)

Were you ever a member of the company?

No. I completed my training at the company school [Instituto Superior de Arte] but I was never in the company. I started with a private teacher, Olga Ferri, at seven, and at eight I auditioned for the Instituto. So every morning I was at the Colón, in the afternoon I went to school, and in the evening I studied with Olga.

Is it typical in Argentina to combine studies at the Instituto with private instruction?

Yes, at least in my generation, that was the norm. Everyone wants to study at the Instituto; it’s free, which is wonderful, and you get in by audition. So it’s very prestigious because only the best get in. But in order to prepare yourself more fully you went to a private instructor.

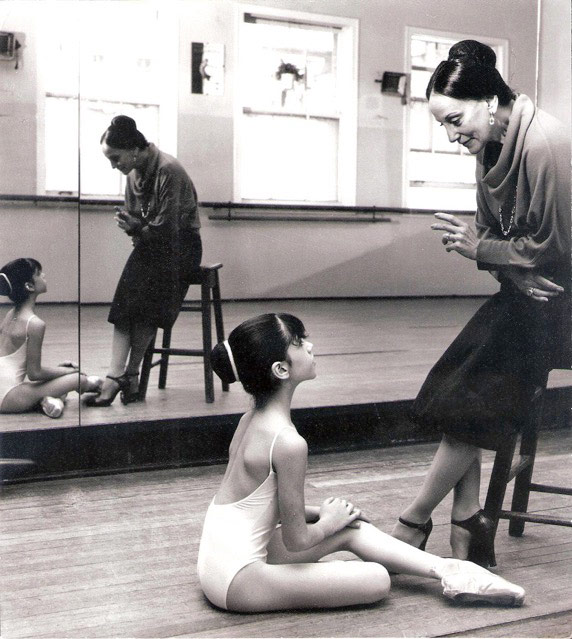

What was your relationship with Olga Ferri like?

My relationship with her was very special. She prepared me for all my competitions and traveled with me. I never traveled with my parents. They’re wonderful people. They never questioned it. They just supported what I wanted to do. It was a very intense relationship; I don’t know if that sort of thing happens nowadays.

Almost like a second mother…

Completely. Almost a first mother. When I was a little girl, dance was everything to me, and Olga told me where to go, what to do. She was my guide. But I still went to the Colón school because it was an incredible base. We studied ballet, jazz, folkloric dance, Spanish dance, languages, music history. It was a very complete training. And I went to a normal school for academics.

© Alicia Sanguinetti. (Click image for larger version)

How would you describe your training?

What we have here in Argentina is a mix of everything. A lot of Russian training and some Cuban. We have these two very different styles. The Cuban influence comes out in the strength of our dancing. A lot of Cubans performed here. And Argentine students went to Cuba to study during the summer. So we have that strength, that drive, and then the style and elegance of the Russians.

What was Olga Ferri’s approach?

She was very open. She had been a principal at London Festival Ballet [predecessor of English National Ballet] and she danced with Nureyev. So she was very open.

Why do you think there are so many good Argentine dancers?

We have very good teachers. A lot of talent. But it’s also that combination of Russian discipline and Cuban intensity. It’s not easy for us here, so if we do make it it’s because we fought for it. We have that hunger, that fire.

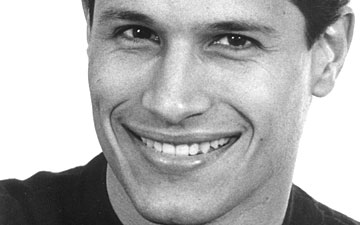

How did you end up at the School of American Ballet?

When I was fifteen I danced at the closing gala for a competition here in Buenos Aires. Hector Zaraspe [an Argentine dancer, choreographer, and artistic director] had been on the jury of the competition. After the gala, he told my parents that if I wanted to go to New York he could get me an audition at SAB. At the time, ABT didn’t have a school. Of course I said yes! Obvio! Where are my bags?

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

How did Olga Ferri react to your decision?

I had recently parted ways with Olga. I left her school. It was too much. I’ve never repeated that kind of relationship in my career. Everything I am is because of my teacher she was like a mother, and she gave me everything. When I left Argentina, I was already fully formed. I’m very grateful to her. But it was too much. The separation was very hard, I felt lost. But then the gala happened, and Zaraspe offered to help me get an audition. It was an incredible time.

What happened next?

I danced the audition – there were no guarantees of any kind – and they put me in the highest level at the school. I stayed in a boarding house run by nuns. I didn’t speak English. I started in the middle of the year, in January. Those six months were incredible. They opened my eyes to new teachers, a new style. At first it all felt very strange. I didn’t know New York City Ballet at all. And then, at the year-end Workshop, Suki Schorer gave me the lead in [George Balanchine’s] Raymonda Variations.

Was it difficult to adapt to Balanchine’s musicality?

No. I’ve always been very musical. Dancers tend to count, but I’ve never done that. I just listen to the music. Olga was like that too.

© Rosalie O’Connor. (Click image for larger version)

How did you go from the School of American Ballet to American Ballet Theatre?

My plan was to study for six months and come home. But I heard that there were auditions at ABT. I went, not expecting to get in; at the time all the corps dancers were American. It was 1991, under Jane Hermann. But I was dying to take class with the company; I’d been watching videos of Cynthia Harvey and Martine van Hamel since I was a kid. To me, they were lo más de lo más, the best of the best. I took class, but I had my ticket to fly back the next day. And ABT took me.

What was it like moving to New York?

It was like emerging from a bubble. Olga was very strict. If you took class with her, you didn’t take with anyone else. I was used to having someone watch me like a hawk in class. Then I got to New York and I went to take class at David Howard studio. You paid, and there were Cynthia Harvey, Gelsey Kirkland, a fifteen-year-old student – me – and someone who had never danced two steps in their whole life. David Howard gave combinations but made hardly any corrections. For me that was a shock. I found it bizarre. In Olga’s class, if there was a professional, she stood at the front. Olga used to say, “the studio is a temple.” Here, those things didn’t seem to matter.

Has that affected how you think about teaching?

I’m teaching a lot now. Because of my experiences with teachers, coaches, and choreographers, I know that a teacher does a lot more than give steps and combinations. You’re transmitting something. My teachers brought out the best and worst in me. You have to help the students. I’m all about discipline–no cell phones, no sloppiness, no tardiness. I hate all of that. But at the same time I don’t believe in making people nervous and so that they can’t work. You have to know the difference between discipline and getting the best out of people.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

Where are you teaching now?

I just finished teaching at SUNY Purchase College, and now I’m off to San Diego I’ve been there the last two years. I taught a girl there, Scout Forsythe, and I said to her, “if you ever go to New York, let me know and I’ll ask Kevin [McKenzie, artistic director of ABT] to see you.” He saw her, and now she’s in the company. I love that. You have to be generous enough to see someone’s talent. I changed her life the same way Hector Zaraspe changed mine.

How did you imagine your career when you were a little girl?

My dream was to be a principal at the Colón. I didn’t know anything then about the problems there with turnover and all of that. [The national retirement age in Argentina is 65, which means that the Colón, like any large institution there, is unable to let people go before that age. As a result, auditions for permanent positions in the company are few and far between.] But the retirement issue has always been a big problem; how do you bring new people into the company? It’s not fair to anyone. The dancers who are sixty don’t want to go on dancing. And they’re taking up spots that could be occupied by young dancers who are dying to dance. It’s bad for everyone. But I never had to face all of this because I went directly from the school to the US. I tend to look at things in a positive light. I tell my Argentine dancer friends, nothing is perfect, no matter where you go. I understand that the Colón has problems, but the US isn’t perfect either. In Argentina dancers have a stability that American dancers don’t have. I think both extremes are wrong. The American extreme isn’t right either. You’re here today, gone tomorrow, and you leave with nothing. I could have stayed in Argentina and worked until I was 65. But that wasn’t what I wanted. You have to look at the positives and decide what is most important.

Has the idea of leaving the stage been traumatic for you?

Not at all. I’m delighted that I planned so far ahead. The last year was very intense. After my final Quixote I just cried and cried. It’s been incredible to say goodbye to my roles one by one. I’m happy. After my last Giselle, I was just floating. I had a year to reflect.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

Why did you decide to retire from ABT with Giselle?

At first, I was supposed to do Alexei [Ratmansky’s] Sleeping Beauty but I told Kevin that it wasn’t the right ballet for a farewell. He said, “but it’s a big deal, and it’s Alexei.” So I danced the premiere in Los Angeles and then I told Kevin, “you know, I just don’t think it’s right.” Ratmansky decided to do it in a very 19th century style, with wigs and old-fashioned choreography and heavy costumes. It was a great experiment and working with Alexei is always a pleasure. But I wanted to say goodbye with a ballet I had an attachment to.

© Gene Schiavone. (Click image for larger version)

What will you miss?

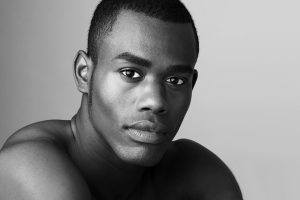

You know, there’s not so much for me to miss. I feel my generation is coming to an end. A new generation is here. It’s great. But my time is over. I felt like I didn’t have much in common with this new generation. My period was unbelievable: Ángel [Corella], José Manuel [Carreño], Ethan [Stiefel], Malakhov, Nina [Ananiashvili], Susan Jaffe…we were all at ABT at the same time. Then they started to leave. I began to feel a little bit like a dinosaur. I don’t know whether the new dancers have that same passion. Now everything is more “light,” not just in ballet, but in life. I don’t know if I like the way things are going. I don’t like the effect social media is having. I love reading books, going to concerts, seeing plays. But now I feel that all anyone wants is to take a picture and say “I was there.” They’re obsessed with showing things. It’s everywhere. At ABT, everyone has their cell phone; at intermission, they’ll tweet things like, “the first act went well.” Me muero!!! [I can’t stand it!] Don’t tell me. I’m sitting in the theatre, in a place where magic is supposed to happen. I don’t want to know that you’re injured, or that your costume came unfastened. I don’t care! Too much information. You lose the magic. My career has been so important to me, and I felt I wanted to end it here, to experience it how I wanted to experience it, fully, intensely. That’s how I want to take my leave, before getting mixed up in all this media. Now, if someone makes it you don’t know whether it’s because they really have talent or because the media helped get them there. I don’t want my career to be tarnished by that sort of thing. I don’t have Facebook or Twitter or any of that.

Do you think you might like to direct a company some day?

I’m too transparent, and not political enough. For me, what’s good is good and what’s bad is bad. I love to coach, I love to teach. I love my art-form.

© Juan Mathé. (Click image for larger version)

Have you thought beyond the end of the year?

Next year I want to dedicate more time to teaching, and finally bring out my clothing line, under the brand Paloma Herrera. I had to go through a long legal battle to register my name, because of Carolina Herrera and Paloma Picasso. But my dad is a lawyer, and he fought hard. It’s a great project: casual, everyday clothing inspired by ballet and ballet dancers. Really good fabrics, nice cuts. Classic. A bit like me.

[…] A few weeks ago, Paloma Herrera and I sat down to talk about her training and career, about moving back to Buenos Aires, and about what she thinks has changed in the world of ballet and in the wider culture. Our chat is now up on the DanceTabs website. […]

Excelente articulo Marina¡¡¡¡¡

i really enjoyed reading your articles on Paloma and violette verdy.

I taught dance history for ten years a long time ago. I did alot of live interviews and Violette was such a help. My success is really due to her.

I want to send to tell her how something which really interested me in the video she

did at the City Center.

I certainly agree about the ballet world today. Paloma is not only talented but a

great human being.

Carmel