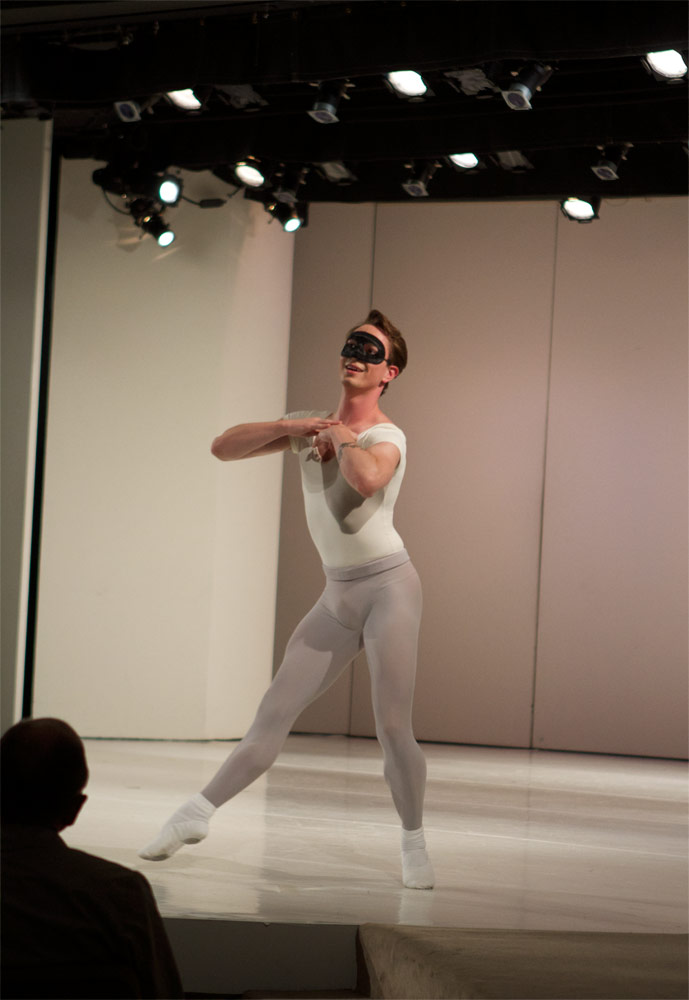

© Works & Process at the Guggenheim/Jacklyn Meduga. (Click image for larger version)

Works & Process at the Guggenheim

Balanchine’s Harlequinade: Commedia dell’arte Explored

New York, Guggenheim Museum

20 September 2015

www.guggenheim.org

The Guggenheim’s Works & Process series invites audiences to observe, as the title implies, a new work of dance, theatre, opera or music in a process-oriented, informal showing and discussion. Their most recent instalment, however, featured two ballets that have long been completed: Marius Petipa’s Les millions d’Arlequin from 1900, and George Balanchine’s Harlequinade from 1965. The ongoing conversation present between the two works, the first a clear predecessor of the second but a poorly notated mystery, kept the event in the realm of the Guggenheim’s regular programming.

Both Petipa’s work, made for the Imperial Ballet (now The Mariinsky Ballet), and Balanchine’s, an early piece for New York City Ballet, have their origins in commedia dell’arte, a theatrical form born in Italy in the mid-1500s. Comprising improvised comedy, stock characters and plots, physical gags and acrobatics, the form eventually took hold in France, where a few familiar characters were born and refined. If nothing else, Harlequin and Colombine are recognizable from their presence in most modern Nutcrackers (except Balanchine’s, where their Act 1 music is his toy soldier dance). The style of commedia dell’arte still lingers in many depictions: the characters are often masked, use pantomime gestures and move with a stiff, doll-like quality.

Petipa first used these characters in his Nutcracker (hence their continuing presence in Act 1 party scenes today) and later created his full-length ballet based on their romance. Harlequin, a joyous, physically agile, lovesick troublemaker, loves Colombine, an ideal woman. How telling that we hear little about what makes her ideal throughout historian Doug Fullington’s discourse on the history of commedia dell’arte. In the Petipa ballet and later in Harlequinade, Harlequin and Colombine love each other, but Colombine’s father won’t allow them to marry. Along with some marital discord between Pierrot and Pierrette, servants whose masters have conflicting interests, this is essentially the story.

Balanchine appeared in Les millions d’Arlequin as a student at the Imperial Ballet School. Though he claims that he used none of Petipa’s steps in his reinvention of the ballet (they only exist in scant notations and the piece dropped out of the Mariinsky’s repertory after the revolution), Lincoln Kirstein said that Balanchine did in fact use Petipa’s steps. How would Kirstein have known what these were? Looking at the same section of the two ballets back to back, as the program was arranged, only complicates the picture.

It is difficult to tell whether the similarities between the two ballets derive from Balanchine’s memory of Petipa’s steps. It is even more difficult to parse out the ways in which the simplistic Stepanov notations outlining Petipa’s footwork are what make Balanchine’s choreography appear more rhythmically complex, more subtle, more intricate than Petipa’s. Kyle Davis and Angelica Generosa, Pacific Northwest Ballet corps de ballet members, demonstrated how Petipa’s choreography is restaged through notation. Reading the libretto and going measure-by-measure through the score, it is apparent that things happen slowly with Petipa. Balanchine can convey in one measure what Petipa expresses in three.

Davis and Generosa tackled Petipa’s pantomime-heavy movement for the duration of the night. It is rather unnatural to Balanchine-trained bodies. City Ballet dancers Tiler Peck, Gonzalo Garcia, Claire Von Enck, and Anthony Huxley are tasked with the more demanding, but probably more natural, Balanchine versions. Generosa is the standout among them, bringing Petipa’s notations to life with wit and charisma as Pierrette. Though Balanchine’s version of “The Reconciliation Polka,” as Pierrette and Pierrot’s pas de deux is called, is more sophisticated in that it does not separate dance and pantomime like Petipa’s does, it struggles to tell the story of reconciliation as clearly as Petipa’s original choreography, simplistic as it may be.

© Works & Process at the Guggenheim/Jacklyn Meduga. (Click image for larger version)

Colombine’s Act 2 variation suggests a different relationship between the two ballets. A woman fully notated the details of Petipa’s version from head to toe – rare on both accounts and a strong case for women taking charge of the movement meant for their bodies. Here, Petipa’s choreography, too, is full of subtleties, most notably lovely, fluttering hand movements. Balanchine interprets the twinkling, lullaby quality with gestures that mimic playing the harp. On Generosa and Peck, both choices convey Colombine’s maturity and quiet strength.

Fullington cited critical reactions to Harlequinade, noting how audiences don’t respond strongly to the piece because it doesn’t offer a “contemporary point of view,” as Arlene Croce puts it. “Balanchine’s re-evaluations occur within the material, not outside of it in the form of a commentary,” she wrote in 1979 in her essay “Balanchine’s Petipa.” And yet, the work remains securely situated in the company’s repertory. It will have its time at the Koch in mid-October.

You must be logged in to post a comment.