© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

New York City Ballet

Fall Gala: Polaris, The Blue Distance, Common Ground, New Blood, Thou Swell

New York, David H. Koch Theater

30 September 2015

www.nycballet.com

The Young and the Restless

Nobody surpasses New York City Ballet in sleekness and urbanity. The company is like a glistening skyscraper: sharp-edged, diamantine and, sometimes, a little cold. So, too, its galas. Stylish patrons glide across the promenade, champagne flutes in manicured hands, ready to coolly admire the newest creations of a handful of bright young things. These new ballets are wrapped in couture by an equal number of names from the fashion world. (For the record, this year the designers were: Zuhair Murad, Hanako Maeda, Marta Marques and Paulo Almeida, Humberto Leon and Peter Copping of Oscar de la Renta.)

As tonight’s gala began, a short, well-crafted film offered a tasteful peek into the process of translating the ideas of fashion designers into workable costumes. Presiding over the construction, fittings and alterations was Marc Happel, king of the costume department, a man of dry wit born of long experience and supreme competence.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

But let’s move on to the dances: four new ballets in quick succession, each about ten minutes long. It’s a lot to take in in one evening. Here they were crammed into one half of a program. The other half was devoted to a Peter Martins party piece from 2003 called Thou Swell. It’s ballroom ballet set to Richard Rodgers songs, complete with onstage band and singers. For the gala, it was costumed by Mr. Copping in shimmering, floor-length gowns and engulfing wraps. (The latter were quickly disposed of.) The ballet was notable mainly for the welcome return of Robert Fairchild, on loan from “An American in Paris” in which he has been playing Jerry Mulligan since the spring.

The four young choreographers – Myles Thatcher, Robert Binet, Troy Schumacher and Justin Peck – are all in their twenties. Two (Peck and Schumacher) are City Ballet dancers. Thatcher dances for San Francisco Ballet. Binet is the choreographic associate of the National Ballet of Canada. (All, obviously, are men. Where are the female ballet choreographers?) Seeing their works back to back in this way inevitably reveals areas of overlapping interest. Could they be generational themes? All the ballets had same-sex partnering of some kind, as well as partnering in which the women took the lead or in some way supported or assisted the men. Two had lonely figures who stood apart from the group. Two ended with the curtain descending as the dancers were still moving about the stage.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

All exemplified the speed and clarity for which City Ballet is known. Myles Thatcher’s “Polaris,” set to the throbbingly romantic first movement of a William Walton quartet – written when the composer was in his teens – had a kind of aquatic feel. The eight dancers linked into chains, undulating like seaweed beneath the surf. (The teal and beige costumes, by Murad, added to the sea-foam effect.) Tiler Peck was a loner, gazing hungrily into the middle distance. At times she was drawn into the group; often she pulled away. Thatcher, who was recently mentored by Alexei Ratmansky under the auspices of the Rolex Mentor and Protegé program, revealed both a sophisticated musicality and an ability to layer multiple strands of movement, one upon the other, in harmonious, constantly engaging ways.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Robert Binet’s “The Blue of Distance,” whose title was inspired by a line from Rebecca Solnit’s “Field guide to Getting Lost” – a book of philosophical essays – was like a negative of “Polaris.” Here a man, Harrison Ball, stood apart from a group of his peers, who included Sara Mearns, Sterling Hyltin, Rebecca Krohn and Gonzalo García. The palette was a shadowy blue (by Maeda). In a darker area to the rear of the stage a few dancers often lingered with their backs toward the audience, slowly raising and lowering their arms. Binet played with hard and soft shapes, straight legs, then bent; bodies tightening, then melting. Around them dripped Ravel’s liquid arcs of notes. (The music, “Oiseaux Tristes” and “Une Barque sur l’Océan,” was played by Elaine Chelton.) The effect was decorative; at times it slid into mannerism, melancholy for the sake of melancholy.

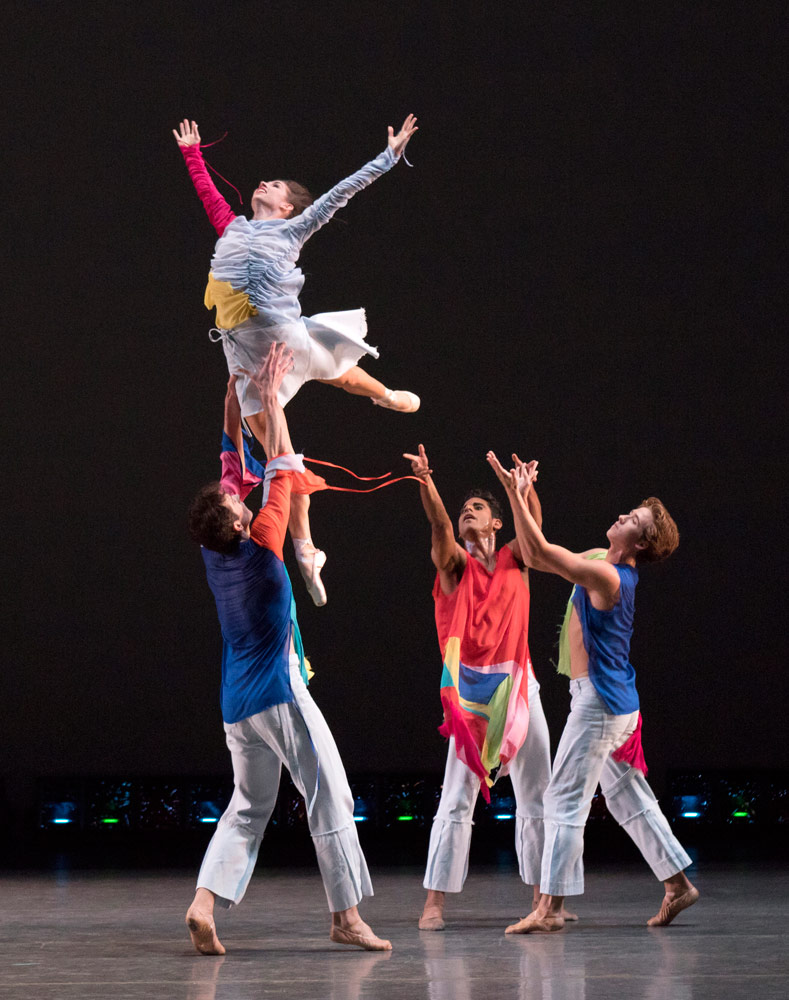

In Common Ground, Schumacher returned to familiar territory; dancers meeting on some sort of playground, throwing ideas at each other, connecting, erupting into bursts of movement. (These bursts were augmented by the fringed, ragged and brilliantly colored costumes by Marques and Alameida, which, though certainly not elegant, were the most original of the night.) Schumacher’s musical collaborator was the young composer, Ellis Ludwig-Leone, with whom he has worked closely in the past. Ludwig-Leone’s music is by turns bombastic, sentimental, driving, and playful. It proceeds in starts and stops, as does Schumacher’s choreography, a characteristic that is both appealingly informal and sometimes frustrating. The dancers in Schumacher’s work look like themselves, young and casual and prone to outpourings of emotion intermixed with episodes of friskiness and awkwardness.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Common Ground contained a beautiful, shyly sexy pas de deux for Ashley Laracey and Amar Ramasar, perhaps the most satisfying male-female pairing of the night. One of the casualties of the exploration of gender equality in many new ballets is the tentative, rambling feel of the pas de deux, but Schumacher is a romantic at heart. Seldom has Laracey (Schumacher’s partner in life) looked so luminous and so free. Even so, Common Ground lost momentum about halfway through. The ending, with two dancers left standing as the curtain came down, felt unresolved.

What distinguished Justin Peck’s New Blood from the other new works was the enormous polish of Peck’s phrasing. His combinations of steps are simply dazzling; one movement flows into the next, and then into something else, breathlessly, tautly, without room for visible preparations or transitions. At one point in New Blood, Adrian Danchig-Waring and Ashley Bouder rose in arabesque and then sank to a squat in what felt like less than a millisecond. Earlier, Claire Kretzschmar hovered on one leg, the other leg shooting up into the air, and held this crazy pose for longer than seemed possible, just to fill a note in Steve Reich’s “Variations for Vibes, Piano, and Strings.” New Blood had a recurring theme: dancers crouching over other dancers, then pumping their chests as if to offer first aid. It’s a funny, odd image. Clever, too.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

What the night was lacking was warmth, a hint of soulfulness. These young choreographers are talented, musical to a man; in their hands, the vocabulary of ballet is as clean and brilliant as it has ever been. But there is a kind of safety in skill. The singlemindedness and sense of purpose that makes us want to see certain ballets again and again – that was missing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.