© Johan Persson. (Click image for larger version)

Royal Danish Ballet, Shaken Mirror (Rystet Spejl), premeire 28 May 2016

June 2013 DanceTabs interview

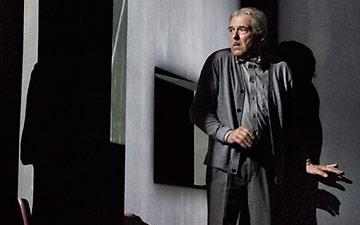

Kim Brandstrup is a choreographer much in demand by ballet, opera and theatre companies (as well as film directors). Recent dance commissions have come from New York City Ballet, the Royal Danish Ballet and Rambert (and he has important future commissions, yet to be announced), after several years when he worked mainly with opera and theatre directors in different countries. His international reputation has blossomed now that he is in his fifties, turning freelance after running his own company, Arc Dance, from 1985 to 2006.

He used to be known as a creator of narrative works for Arc, attracting exceptional dancers and future choreographers. Arc was very unusual, at the time, for telling stories in a contemporary dance idiom to specially written scores. Brandstrup had to fight for funding, eventually giving up the struggle. ‘It had become such a battle, finding touring venues and constantly applying for yet more funding’, Kim says ruefully. ‘Arc had been been my family when we were all much the same age, with similar experiences, but then as I grew older I needed to find a different direction – to stop being in control.’

© Ben Delfont. (Click image for larger version)

When he was invited by Monica Mason to work with Royal Ballet dancers, he found that he was interested in another kind of expressiveness. ‘Zenaida Yanowsky and Alina Cojocaru gave me ‘close-ups’ of emotions, so I could create cameos with them – solos or duets. I didn’t need to tell them what character they were or what they were feeling. They understood through the music I’d chosen. Tamara Rojo asked me to work with her on Bach’s Goldberg Variations for the Linbury theatre, so we could develop ideas on an intimate scale. I’d commissioned a lot of music for Arc, having to describe and even dictate what I wanted from composers – then, with the Royal Ballet dancers whose musicality is embedded in their training, the music took over. I abandoned narrative for lyrical.’

Brandstrup had started his career in Denmark (he was born in Aarhus in 1957) by studying music and film. When he became fascinated by dance, he’d had only 18 months of technical training before he was accepted by the London Contemporary Dance School at the age of 23. He smiles dismissively. ‘I always say I came to The Place with an ear and an eye, but I came without legs.’ He was fortunate in having exceptional teachers who saw something in him. He owes a great deal, he says, to Nina Fonaroff, who encouraged him from the start. ‘She let me be who I am, while directing me towards a foundation in dance that I hadn’t had before.’

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Nina Fonaroff had danced with Martha Graham’s company, becoming assistant to the musical director, Louis Horst, between 1937-1950. Later, Fonaroff had run her own company until she accepted Robin Howard’s invitation to teach choreography at the newly-founded London Contemporary Dance School. (She taught later at the Northern School of Contemporary Dance in Leeds.) According to Kim: ‘She was incredibly analytical, but it never showed. Nothing was prescriptive – she was always respectful to who I was as an individual, letting me find my own way.’

He follows Fonaroff’s precepts whenever he mentors choreographers. He started doing so with members of Arc between 2001 and 2005, and then established the DanceLines summer courses for professional choreographers at the ROH. In his view, ‘You have to give so much space to whoever you mentor. You don’t know who they are and they don’t know either. I’ve always been interested in the mechanics of choreography, but the most important thing is to say, “Just do it”. It’s only afterwards that you can start reflecting on what you’ve done.’

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

He is wary of the focus in contemporary dance institutions on ‘finding your own voice, developing your own vocabulary, inventing your own movement language’. Though such advice can seem helpful at first, he believes it becomes a trap. ‘There’s a lure in thinking that you find the true self ‘inside’ your body. I think creative work has to be driven by an idea – an idea external to the body – it’s in the meeting with something other than yourself that something new happens. This ‘other’ can be anything – the music, a story, an image, an architectural landscape, a dancer. But it is an external impulse that ignites you. The body is such a creature of habit that it keeps reverting to what it knows. You see choreographers, however innovative they are – even Martha Graham, with all the discoveries she made – repeating themselves. After a while, their ‘signature’ becomes predictable.’

© Dave Morgan.

That is why he prefers ballet as a training method. ‘It’s a technique of moving, of training your reflexes – it doesn’t have to be an entire aesthetic based on tradition. Provided it’s not taught as a syllabus, which closes the door on what’s possible, you can use it how you want. You don’t have to ‘define your vocabulary’ or invent ways of moving in order to come up with something new.’

I suggest that he has the advantage of not having been a physically exceptional dancer himself, so that when he choreographs, he doesn’t ask dancers to copy his movements. A tall, burly man, not trained as a ballet dancer, he doesn’t have a distinctive way of moving. ‘Oh, I do demonstrate’, he protests: ‘You have to. But it’s for timing and phrasing, not steps or physical details. I’m very specific about counts, about how time is structured. That’s how you keep renewing yourself, by finding different impulses and rhythms. You open up a sequence to let the dancers contribute their own responses, particularly if they are musical. For me, the music determines how long something lasts, how many people there are on stage at any one time, who comes and goes.’

© Dave Morgan, courtesy the Royal Opera House. (Click image for larger version)

For the past few years, he had been collaborating with directors of opera and other forms of musical theatre before returning to dance companies in 2014. ‘I’ve been very lucky to collaborate with fabulous directors who treat me as an equal partner, not ‘just’ the choreographer.’ He mentions Deborah Warner in particular, but he has also worked with Fiona Shaw, Pierre Audi and Jonathon Kent, among many others. He is gratified at being able to revisit Benjamin Britten’s Death in Venice several times since his first go in 1992, for Colin Graham’s Royal Opera production. ‘I’d found Britten so alien then’, he says. ‘I wouldn’t have chosen his music myself, but I came to understand him when I worked with Deborah Warner on Death in Venice in 2007 [and later revivals]. That’s why I did Ceremony of Innocence to his music for the Royal Ballet at the Aldeburgh Festival in 2013, the centenary of his birth.’ The ballet, to Britten’s Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge was performed at the Royal Opera House the following year.

Brandstrup found that he came back refreshed to his dance commissions, including a short film based on the myth of Leda and the Swan, for Zenaida Yanowsky and Tommy Franzen (2014). ‘I realised that I could return to narrative without having to spell out cause and effect. I could present a scene in which the audience would understand the performers’ emotions and moral dilemmas without having to read a long programme synopsis or think they ought to know a book or play already. The dancers supply a commentary to the music; it’s as in the cinema, if you get a close-up right, the spectators provide the character’s thoughts and feelings.’

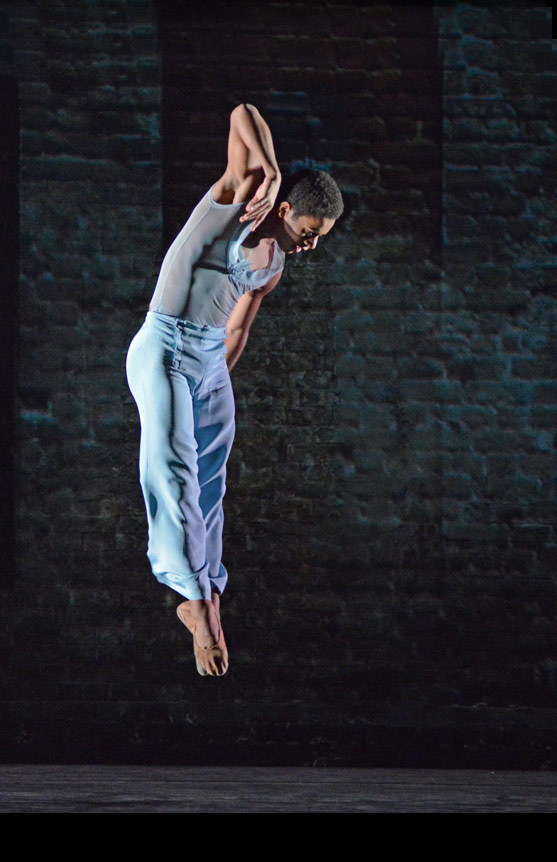

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Wendy Perron in Dance Magazine remarked of his Jeux for New York City Ballet in October last year that it was like an Ingmar Bergman film, ‘bringing you inside the mind of a confused, lost young woman.’ Brandstrup choreographed Jeux to the Debussy score for Nijinsky’s 1913 ballet of the same name, adapting the enigmatic scenario into a series of games of courtship and deceit, with Sara Mearns as the principal woman. ‘I wondered how City Ballet dancers would respond to me because they’re not so used to dealing with stories’, Kim says. ‘But of course they perform Jerome Robbins’s ballets as well as Balanchine’s, so they recognised what I was getting at.’ Mearns had expressed her surprise in an interview for the New York Times that Brandstrup wasn’t telling the dancers what steps to do and where to do them: ‘Then we realised we are out of our comfort zone but we are really free. He is directing us, but he will let us go where we want with the movement.’

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

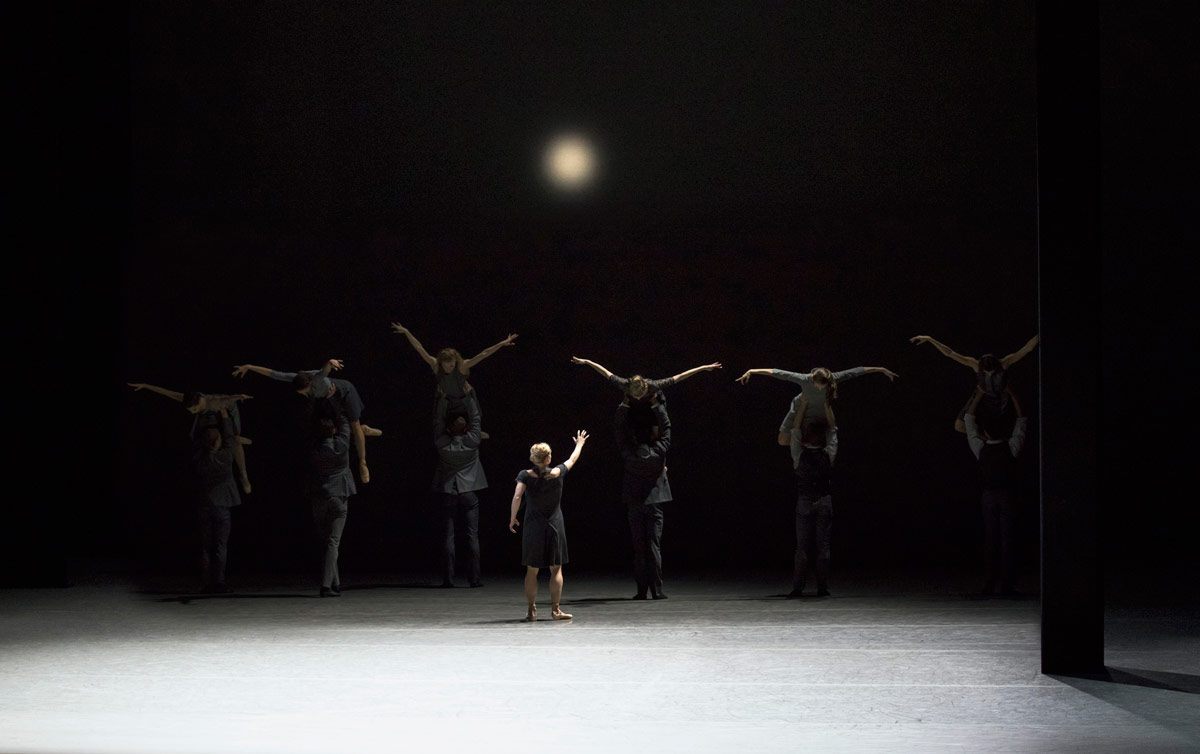

Jeux is revived this month in a programme of five recently commissioned works for NYCB – the other four by younger choreographers. At the October premiere, Brandstrup’s contribution aroused the most interest: critics were intrigued by its elusive relationships and the sensitive way he used Debussy’s complex score. Transfigured Night for Rambert, given its London premiere a few days later, also received critical acclaim. Set to Schoenberg’s Verklaerte Nacht, it alludes to the poem that inspired the music. A woman has to tell her true love that she is bearing the child of another man: although he nobly forgives her in the poem, Brandstrup’s contemporary ballet proposes three different reactions, conveyed through two couples and a corps of witnesses. ‘Mark Baldwin [Rambert’s artistic director] gave me the chance to use that music’, Kim says. ‘It tells so much, and it’s so dramatic that I had to have more dancers than just the main couple. Mark gave me the luxury of six weeks’ uninterrupted rehearsal where I could choose the dancers I needed each day. Big ballet companies can’t do that – you have to negotiate tight rehearsal schedules.’

© Foteini Christofilopoulou. (Click image for larger version)

His next commission from the Royal Danish Ballet, his sixth for the company, will be based on poems by a renowned Danish poet, Soren Ulrik Thomsen. To be called Shaken Mirror (Rystet Spejl), it will have its premiere on 28 May on the revolving stage of Copenhagen’s Royal Danish Playhouse. It’s to be a full-length work, using a range of dancers aged between 6 and 60. When we spoke, Kim was still considering how he would make use of Thomsen’s poetry, which tries to capture what words can’t express. ‘I’m working on video projections with Leo Warner, maybe projecting some of the words and using the stage as a mirror. We’ll see’, he says. ‘You have to work through ideas to let things happen.’ All he knows is that Shaken Mirror will be quite different from anything he has done before.

You must be logged in to post a comment.