© Daniel Boud. (Click image for larger version)

Australian Ballet

Symphony in C, Diana and Acteon pdd, Grand pas classique, After the Rain pdd, Little Atlas, Scent of Love

★★★✰✰

Sydney, Opera House

29 April 2016

australianballet.com.au

www.sydneyoperahouse.com

There was more than a hint of Russian heritage in the Australian Ballet’s Symphony in C program, which included five other divertissements in addition to the ballet that gave the program its name, George Balanchine’s Symphony in C. The Balanchine work has the formal, grand Russian look of Petipa, albeit with the addition of some lovely, lyrical, Balanchine-style moments. In addition, two of the divertissements, Victor Gsovsky’s Grand pas classique, and Agrippina Vaganova’s Diana and Acteon pas de deux, recall moments from the 1950s and 1960s when Russian-trained performers brought their classical dancing to the West and stunned us all with their spectacular movements. Along with these three offerings, the first part of the program also included the pas de deux from Christopher Wheeldon’s After the Rain, and two brand new, short works, Alice Topp’s Little Atlas, and Richard House’s Scent of Love.

© Daniel Boud. (Click image for larger version)

The first thing to say about Symphony in C is that the Australian Ballet’s corps and soloists had been rehearsed and coached with technical perfection in mind and there was little to fault with their execution of the steps. A standout performer was soloist Benedicte Bemet who always brings something more than technical exactness to her dancing. My eyes were instantly drawn to her joyous dancing in the third movement, ‘Scherzo’. Pleasure at being onstage, pleasure in dancing, both just stream through her body. It becomes pure pleasure to watch her.

© Daniel Boud. (Click image for larger version)

Looking further, Symphony in C is an ideal opportunity to see eight principal dancers, four leading couples, in the one work. It was good to see Leanne Stojmenov back on stage after the birth of her first child last year: she danced the lead with Kevin Jackson in the first movement, ‘Allegro Vivo’. It was Jackson, however, whole stole the show in this movement. Despite dancing very nicely, Stojmenov never really looked like the star that she can be and seemed to take some time to warm to the part. Jackson, on the other hand, was a powerful presence the instant he came onstage, looking very inch the principal dancer, and partnering with assurance and care. ‘Ballet is woman’, one of Balanchine’s more famous quotes, didn’t apply here. Similarly, in the second movement, ‘Adagio’, led by Amber Scott and Adam Bull, it was Bull that I kept watching. And it was the same again with the other two movements led by Ako Kondo and Chengwu Guo and Lana Jones and Andrew Killian. It was the night of the premier danseur. But I guess what I really missed, and what I have most enjoyed about Symphony in C on other occasions from other companies, was the excitement that comes from watching the leading couples express through their dancing the different qualities of the music in each of the four movements. There was too much uniformity in the production for my liking.

© Daniel Boud. (Click image for larger version)

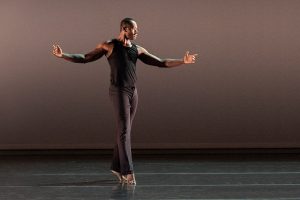

As for the divertissements that made up the first half of the program, Ako Kondo and Chengwu Guo danced Diana and Acteon in spectacular style. Guo took my breath away (again) with his elevation, his beats, and his manèges of jumps and turns. He tossed his body into seemingly impossible shapes as he moved around the stage, and as he threw himself into those final poses at the end of each of his variations. In the Gsovsky pas de deux, Miwako Kubota and Brett Chynoweth could not quite match the attack of Kondo and Guo and I longed for something a bit more seductive and alluring from them. Technical proficiency and a good smile is one thing, but the body needs to display its physicality a little bit more than Kubota and Chynoweth managed to do.

© Daniel Boud. (Click image for larger version)

Robyn Hendricks has always looked good in After the Rain. This time she was partnered by guest artist Damian Smith, whose individualistic interpretation of the male role brought a whole different quality to Hendricks’ performance. Smith often exhibited strength and power, which made Hendricks seem vulnerable, especially when her very slender frame and his more solid body were close together. At other times Smith looked vulnerable himself as if held spellbound by Hendricks, which seemed to give her the dominant role. Their partnership generated a range of emotions I had not seen before in this work.

© Daniel Boud. (Click image for larger version)

Scent of Love and Little Atlas were the works of two emerging choreographers from within the Australian Ballet’s ranks. Both began strongly, largely as a result of striking visual elements: an expanse of red cloth in the case of Scent of Love and a suspended circle of lights with Little Atlas. Richard House’s Scent of Love, made on two couples and danced to music by Michael Nyman, was evocative in tone and filled with some lovely swirling movement. I admired the partnership of Amanda McGuigan and Christopher Rodgers-Wilson in particular but wish the lighting had not been so ominously dark so that I could have enjoyed the work of the other couple, Amy Harris and Jarryd Madden, a little more.

© Daniel Boud. (Click image for larger version)

Alice Topp’s Little Atlas was performed by Vivienne Wong, Rudy Hawkes and Kevin Jackson to music by Ludovico Einaudi. Topp’s theme of memories and connection to the past was not an easy one to get across to an audience, not even with the aid of that circle of lights, which, as it shifted position at various times, seemed to represent the changing nature of memory. Choreographically Topp chose a contemporary style of movement, which occasionally looked somewhat ungainly, especially the movement created for Wong, who often seemed to find herself upside down in awkward-looking poses. Topp has spent some time observing Wayne McGregor at work but has not yet managed to make every move of every kind look perfectly in context, as McGregor does. Nevertheless, it was a privilege to see House and Topp move up from choreographic workshop to mainstage production and I look forward to seeing more of their work.

© Daniel Boud. (Click image for larger version)

Overall this program was an eclectic, somewhat uneven one. More than anything I continue to ponder why I never feel the thrill of the dance that I should from the Australian Ballet, especially when they are dancing major classical works. It’s great to aim for technical perfection but I will always be looking for something more than that.

You must be logged in to post a comment.