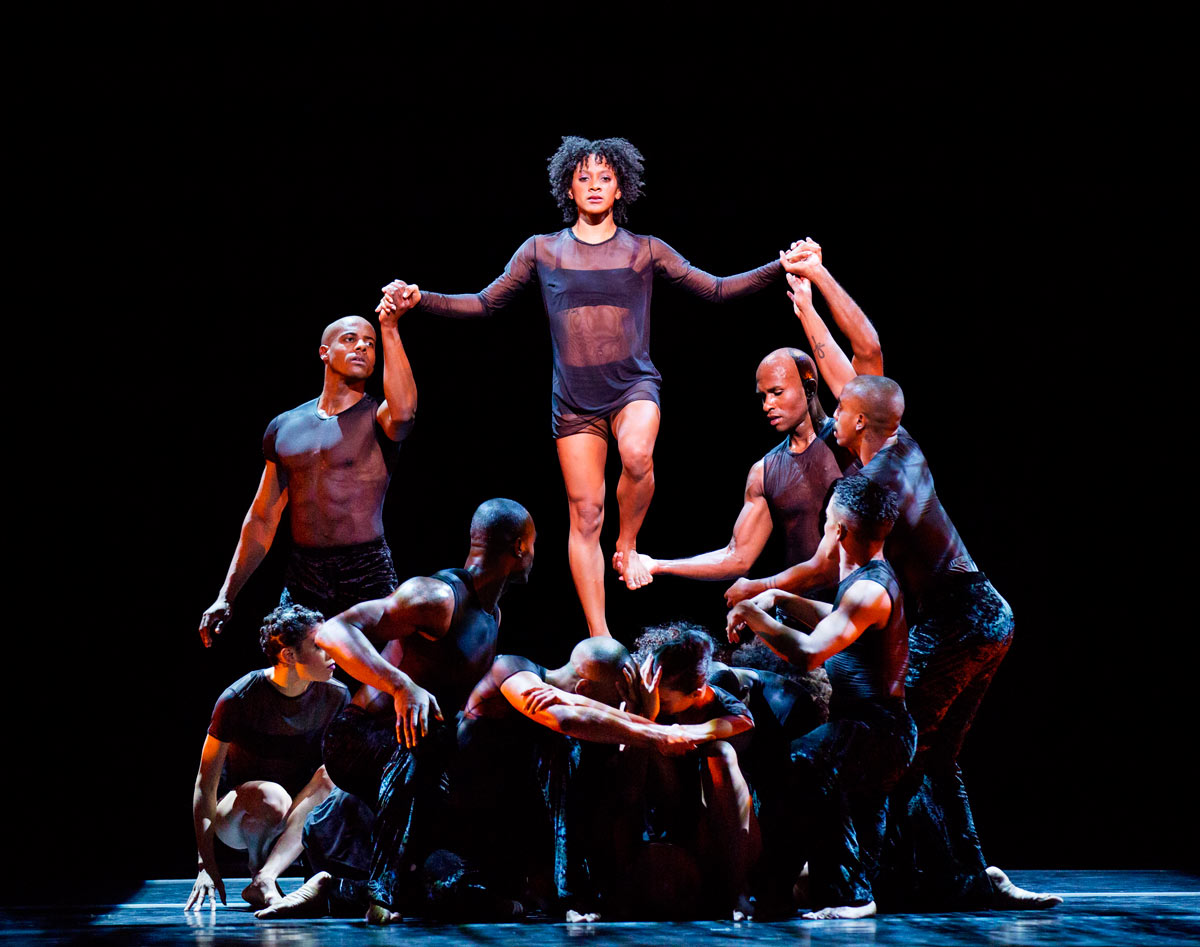

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

June 17: Open Door, Untitled America: Second Movement, No Longer Silent, Exodus

June 18 mat: Deep, Vespers, The Hunt, Revelations

★★★✰✰

New York, David H. Koch Theater

17, 18 (mat) June 2016

www.alvinailey.org

davidhkochtheater.com

Joy and Pain

It’s a truism that any afternoon that includes Alvin Ailey’s Revelations is apt to leave you happy. The June 18 matinee of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, at the Koch Theater in Lincoln Center, was no different. The Ailey classic ended as it always does, with an encore of “Rocka My Soul,” a dance that seems to encompass all the joy and heat of a summer afternoon among friends. The dancers’ knowing glances – here we go again! – are part of the fun. By the end of the performance, the entire audience was dancing in the seats, as it always does. The afternoon’s Revelations included an understated but silkily phrased rendition of the pleading solo “I Wanna Be Ready” by the golden-haired Michael Francis McBride, and a very touching, and, again, simple performance of the “Fix Me, Jesus” duet by Constance Stamatiou and Jeroboam Bozeman. Bozeman, in particular, is having a standout season. His dancing has impressive focus, sharpness, fire.

Revelations managed to elevate what had otherwise been a rather gloomy afternoon. The three previous works were dressed in black, performed on a dark stage, dimly lit. Only Robert Battle’s The Hunt (2001), an exhibition of ritualistic male bonding for six men in long black skirts set to loud, throbbing rhythms – and yelling – by Les Tambours du Bronx, had any affect at all. (However its aggressively testosterone-driven tone wore thin.) Mauro Bigonzetti’s Deep, one of the season’s two premières, turned out to be anything but. Set to moody songs in English and Yoruba by the folk-inflected vocal duo Ibeyi, the dance felt almost like a music video. Much of it consisted of tortured duets in which women were pushed and pulled, or worse, dragged; yearning eyes, gazing toward the horizon; unison grooving; tepid vogueing. It was both overlong and insubstantial. The Ailey dancers gave it their all, as they always do, but could make little of the thin material.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

The piece that followed, Vespers, by the late Ulysses Dove, is a kind of hyper-kinetic, American version of Anne Teresa De Keersmaker’s Rosas Danst Rosas. To a driving score for drum machine (by Mikel Rouse), first two, and then six women in school-marmish black dresses sit and stand and tilt and jump off of chairs, repeating sequences of movement with absolute precision, like particles in a machine. These movements – sometimes explosive, sometimes minimal – are complemented by small gestures, a turn of the head or smoothing of the skirt. It’s not a bad piece, but it feels somewhat over-familiar.

I caught the other season première, Kyle Abraham’s Untitled America: Second Movement, on the previous evening. It is the second installment of a three-part piece by the choreographer, a recent MacArthur grant recipient, the first of which was unveiled last winter. Its theme is extremely timely – the pain inflicted by the high rates of incarceration in the black community. The grim atmosphere is set, first, by a work song, and then by voices (mostly male) discussing what they’ve lost – “I can’t change the past,” one says – or detailing the duration of their sentences. Men and women emerge from the darkness, looking back or into the wings, and are slowly lowered to the ground, their arms clasped behind their backs, or led away, into the darkness. A man and woman face off, mirroring each other, as if communicating from a distance. A man dances a desperate solo, arms whipping and legs unfurling as he spins. Once again, Jereboam Bozeman made a strong impression. And yet, there is something static about the piece, as if Abraham were almost paralyzed by the weightiness of his subject. The portrait doesn’t evolve or develop; ultimately, the piece’s formality blunts its impact.

Formality is the defining feature of Robert Battle’s No Longer Silent, which was performed on the same program. The score, Erwin Schulhoff’s 1925 Ogelala, is a neo-Primitivist dreamscape, owing much to both Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and his Petrouchka. Heavy, syncopated rhythms drive the action. Here and there one hears a muted trumpet or Andean-sounding flute. The score was written to accompany a ballet about a pre-Columbian Mexican warrior. Packs of dancers in unisex black suits shuffle, stomp, and drag themselves around the stage in crisp formations: circles, lines, wedges. The overriding emotion is fear, verging on panic. They could be prisoners in a concentration camp. Dancers take turns playing the sacrificial victim. There is a suggestion of rape. The fear and violence are highly controlled: rhythm and stylized shapes predominate. There is a strong whiff of Martha Graham in the patterns and angular bodies. No Longer Silent is a polished, well-made piece about the dehumanizing effects of terror that at times feels utterly contrived.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

On the same program, two works, Ronald K. Brown’s Open Door and Rennie Harris’s Exodus (both from 2015), showed off the company’s most appealing qualities: warmth, glamour, through-the body dancing. Brown’s Open Door is a free-flowing, open-hearted suite set to Latin Jazz played (on a recording) by Arturo O’Farrill’s Afro-Latin Jazz Orchestra. It has Brown’s characteristic open structure, moving effortlessly from one idea and formation to the next, slowly building toward a state of salsa-infused bliss. Exodus, though darker, also contains hints of exaltation, sustained, in this case, by the throbbing beats of house music. The basic dance-language is hip-hop, and the dancing is through the body, involving knees and backs and arms. But it’s also light. The dancers’ sneakers imbue their quick foot-work with a bouncy, buoyant feel.

Like Kyle Abraham’s Untitled America, Exodus touches upon dark themes. Shots ring out, bodies crumple, a woman mourns. But it suggests redemption as well, through common action and angelic presence. “There are Angels among us,” a voice says, as white-clad dancers slowly fill the stage. First among them, Jamar Roberts, monumental, heals and sustains his flock. Roberts’ dancing has both power and gentleness. As he falls and rises and falls again, he seems to take on all the troubles of the world.

© Paul Kolnik. (Click image for larger version)

Joy and pain. The Ailey dancers are particularly adept at showing these basic truths about our existence. The best works in their repertory, like Revelations and Exodus, allow us to go there with them. This is dance as an expression of our common humanity.

“It’s not a bad piece, but it feels somewhat over-familiar.” “Vespers” was created in 1986 and had its Ailey premiere in 1987. It didn’t feel overly-familiarly then. If anything it felt gripping and almost religious. If you feel this way about “Vespers” then does “Revelations” which “the entire audience was dancing in the seats, as it always does” also feel over-familiar? Thou shalt not contrive logical fallacies.