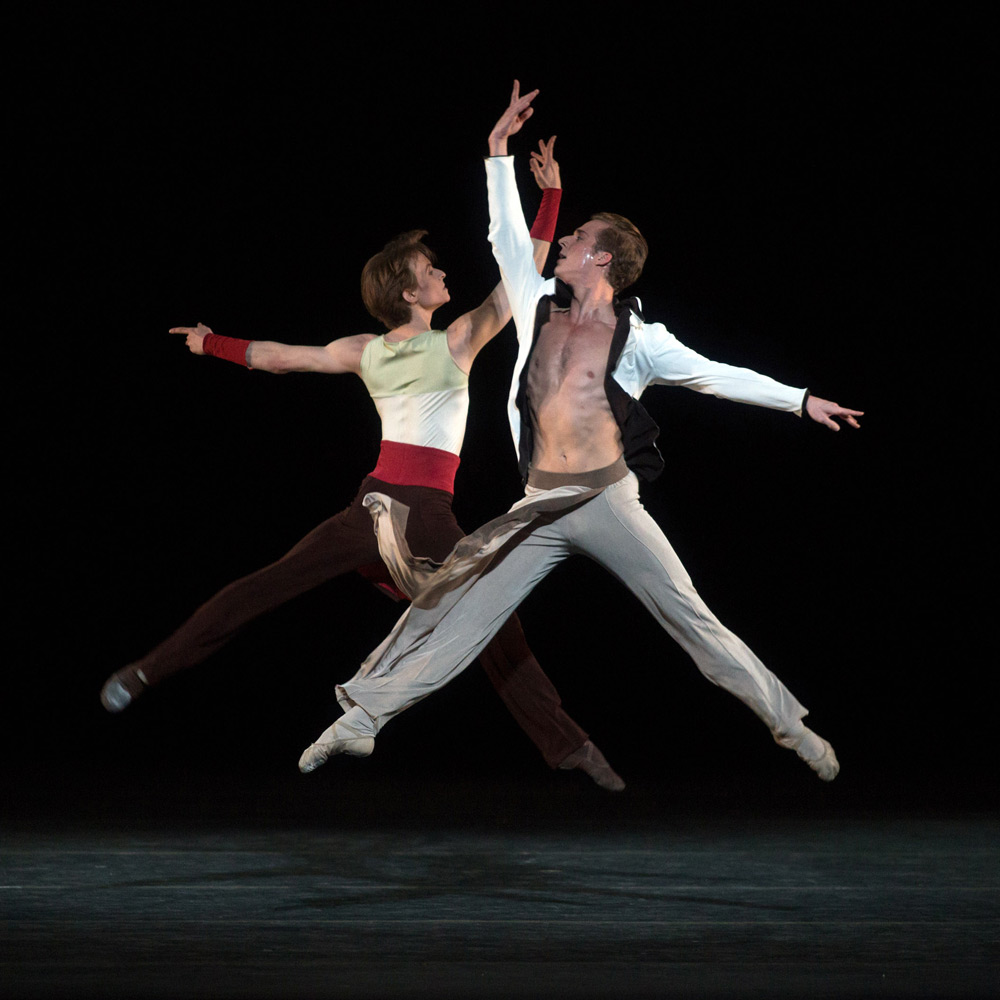

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

American Ballet Theatre

19 Oct: Serenade after Plato’s Symposium, Symphonic Variations, The Brahms-Haydn Variations

20 Oct, Fall Gala: Rondo Capriccioso, Symphonic Variations, Daphnis and Chloe

★★★★✰

New York, David H. Koch Theater

19, 20 October 2016

abt.org

davidhkochtheater.com

In a Garden

Ever since New York City Opera’s demise, there has been an abundance of dance at the house formerly known as the State Theatre. Just last week, New York City Ballet was performing Dances at a Gathering and Balanchine’s Firebird. And now it’s American Ballet Theatre’s turn. Once in a while its worth remembering how lucky New Yorkers are to have two such companies, with such dramatically different repertories and styles and a bottomless supply of exceptional dancers, in their midst.

Not to get too misty-eyed, but the first two performances of the two-week-long ABT fall season have revealed a company in good form, with talent through the ranks and a young roster of appealing, versatile rising soloists and principal dancers. The recent emphasis on promoting from within has paid off, particularly among the women. Performances by Devon Teuscher, Skylar Brandt, Christine Shevchenko, and Cassandra Trenary (among the soloists) and Isabella Boylston, Gillian Murphy, and Stella Abrera (principals), have already made strong impressions. In contrast, many of the exciting men in the company, like Jeffrey Cirio, James Whiteside and the new Danish dancer Alban Lendorf, are recent acquisitions. Others, like Blaine Hoven, Calvin Royall III, and Gabe Stone Shayer, are slowly and steadily working their way up the ladder. All of them are worth seeking out.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

The better the material, the richer the dancing. A second look at Alexei Ratmansky’s Serenade after Plato’s Symposium confirms the impression formed last season. It is a fascinating work that represents a new direction for the choreographer. The ballet, which is danced by seven men and one woman, manages to capture the viewer’s imagination from its first notes, a melancholy, questioning phrase for the violin, later answered by the other string instruments. The score is a violin concerto by Leonard Bernstein, played with a shimmering sound by Benjamin Bowman.

A central figure (here, Jeffrey Cirio), offers a kind of soliloquy, expressed in a mixture of dance and gesture. Ratmansky’s deployment of the dancers’ arms, hands, and torsos is especially articulate. Their forearms zig-zag side to side, as if to clarify a point; men lean against each other or crumple to the ground. They arch their backs forward and extend their arms, as if they had sprouted wings. At one point, they bourrée across the stage like this, like moths drawn to a flame, or angels descending to earth. Each man dances in a different style – with a different voice – at first alone, then in conversation with the others. The feeling evoked by the choreography, by the movement itself, is constantly shifting; Ratmansky has managed to capture the individual qualities of each dancer, of the music at any given moment, and of the character he is portraying, all with stirring truthfulness. The characters are drawn from Plato’s Symposium, a series of dialogues on love. The musicality is sophisticated: there are canons, calls and responses, imitations, accumulations. But more than anything, the choreography overflows with feeling. One can practically hear the characters’ voices as they tell us their stories: Calvin Royal’s almost hopeless loneliness, Cirio’s deep thought, Daniil Simkin’s boyish boastfulness, Gabe Stone Shayer’s silken seductiveness, Marcelo Gomes’s gravity.

The pas de deux between Gomes and Devon Teuscher, who shows up midway through the ballet, is something of a puzzle. Who is this woman? Why is she there? She seems to represent something apart from the others, not a human relationship but a figure of fate – the tragic dimension of love. I’m still not convinced by the end of the ballet, though: it seems too rushed, too busy, to abrupt. Though it matches Bernstein’s mad dash to the finish, it doesn’t quite wrap things up. But that’s a small qualm; this is an extraordinary ballet that begs to be seen more than once. Let’s hope it stays in the repertory for a long while.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

Frederick Ashton’s 1946 ballet Symphonic Variations is back after a ten-year absence. After seeing two performances, with two different casts, I’m still unsure how I feel about it. It’s beautifully constructed – as formal and balanced as a French garden – but rather static. The sense of stillness is built in, part of the architecture of the dance. Often, two or three or four dancers move while the others stand, one leg crossed over the other, framing the stage. (No-one ever leaves the stage.) I kept thinking of caryatids or statues in a garden. A lovely image, but a little staid, like the sparkly headpieces (for men and women), and the rather matronly hairdos for the women. At the same time, there are passages of searing beauty, like a long, enigmatic sequence of bourrées, low lifts, and running steps that seem to glide along a murmuring wave of arpeggios on the piano (played by Barbara Bilach). The dancers appear to move on a cushion of sound.

The ballet may be somewhat dated, or the impression may be caused by the dancers’ lack of familiarity with its stately, architectural style; they look a little constrained and the shapes don’t breathe enough. Even so, three dancers stood out: Calvin Royal III, with his long arms and lyricism, as the Apollonian central male character in the first cast. And, in the second cast, Jeffrey Cirio, remarkable for his clarity. As well as Devon Teuscher, whose quiet authority made the choreography look grave and unadorned rather than prim.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

On opening night, the company gave a rapturous performance of Twyla Tharp’s Brahms-Haydn Variations, even better than last season. It’s a maximalist work, an avalanche of steps and bodies, impossible to keep track of. But danced like this, with joy, sensuality, and humor, it glows from within. Gillian Murphy and Marcelo Gomes sizzled in a sexy pas de deux full of slithery lifts, straddles and hip shimmies. Isabella Boylston and Alban Lendorf exploded on the stage; he tossed her so high you weren’t sure where she would come down.

The second evening (Oct. 20) was a gala program, a bit shorter than the first. After the charming Rondo Capriccioso for the pupils of ABT’s affiliated school (the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School) came the second cast of Symphonic Variations, and then the company première of Benjamin Millepied’s Daphnis and Chloe. It was made for the Paris Opéra at the start of Millepied’s brief and reportedly unhappy tenure as artistic director, and it was well received there. But its New York premiere felt like a major disappointment. Despite beautiful lighting (by Brad Fields), a sumptuous score by Ravel, and handsome set designs by the French artist Daniel Buren, the ballet is flat and overlong, repetitive and aimless. Worst of all it’s vague, unspecific in its mood, action, and movement vocabulary.

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

The story is drawn from an Ancient Greek pastoral about young love. The program note calls it a “sentimental education.” A boy (Daphnis) loves a girl (Chloe); the two are tested and tempted by a vixen (Lycenion) and two villains (Dorcon and Bryaxis). None of this is terribly clear. Millepied has so completely cleansed the plot and flattened out the characters that all we see is two lovers (Stella Abrera and Cory Stearns) mooning about and holding hands, a seductress (Cassandra Trenary) having her way with Stearns, a slightly creepy fellow (Blaine Hoven) skulking about, and a flashier character (James Whiteside) dressed in black, whipping off the only exciting choreography of the ballet.

They do their best with the thin material. The costumes (by Holly Hynes) are attractive: loose-fitting shorts and tops for the men, and long, plain dresses for the women, mostly in white. But they’re just pretty; they tell us nothing about the characters or the situations they find themselves in. The same goes for the striking designs by Buren, translucent rectangles and circles of different colors that rise and fall at seemingly random moments. Nice to look at, and totally opaque. Why are they there?

© Marty Sohl. (Click image for larger version)

And the steps: with the exception of a long, gushing pas de deux toward the end, most of the choreography is colorless. Ravel’s score, gorgeous as it is, is also a challenge. An hour long, repetitive and composed of overextended sections punctuate by wild climaxes, it forces the dancers to do the same things for a very long time. A scene for a group of nymphs and the sleeping Daphnis seemed like it might never end. Even though it was composed for the Ballets Russes – and used by Michel Fokine – and was used again by Ashton in 1951, it seems more suited for the symphony hall than for the stage. Millepied certainly has not managed to make heads or tails of it.

It’s too bad. But one failed new ballet is not enough to mar a season. There’s some hope: Jessica Lang’s new work, Her Notes, premières on the 21st. And there’s always Serenade after Plato’s Symposium.

You must be logged in to post a comment.